“Oh honey, my family’s been working for the Church for a long time.”

I knew from the playful twinkle in her eyes, the seriousness on the rest of her face, and the way she said “long” that she didn’t mean her mother had been the parish secretary before her. She meant her family had been working for the Church for a very, very long time — and not by choice.

I had just met a descendant of slaves. I, a Maryland Province Jesuit and alumnus of Georgetown University, was standing face-to-face with a woman whose biological forebears were the slaves of my spiritual forebears. I don’t think my jaw dropped, but my heart certainly fell.

***

In 1838 The Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus sold 272 men, women, and children. Prior to that sale, slaves had been used to maintain plantations that helped support and finance the activities of Maryland Jesuits, including the operations at Georgetown. Jesuit leaders eventually concluded, however, that slaves were no longer an economically viable model for maintaining operations.

As a result, these 272 people were sold for $115,000, which is the equivalent of approximately $3 million today. Some of the money of the sale was used to pay off construction debts at Georgetown, and so helped to keep the school open. Several decades later and for unclear reasons, two buildings at Georgetown were named after the two Jesuits who organized the sale.1

***

I’ve known Georgetown and the Maryland Jesuits owned slaves for a while. I first learned about it from a Jesuit I met in college.

After I entered the Jesuits, that same Jesuit took my fellow novices and me on a tour of the part of Maryland where the Society of Jesus first came to what became the 13 original colonies. We learned about the Jesuits’ participation in a voyage across the Atlantic driven by a desire for religious tolerance, the early efforts of Maryland Catholics to peacefully coexist with local Native Americans, and how the Maryland Jesuits not only survived the Universal Suppression of the Society of Jesus but managed to come out of it a full nine years before the Suppression was officially lifted by the Pope. We got to visit the longest continually-operating Catholic parish in the country and a number of original missionary outposts dating back to the 17th century.2 Finishing that tour I felt like I was standing on the shoulders of giants. I was proud.

As an alumnus of Georgetown University I was even prouder. My alma mater looms large in the history of the Jesuits in that region, and when I learned how Georgetown can trace its roots all the way back to 1634 I was all set to declare Georgetown the oldest university in the country. (#sorrynotsorry, Harvard!)

And our Jesuit guide taught us more about the slaves. At that point, the best evidence suggested that some of the proceeds of the sale of the slaves had gone to support the expenses of Jesuits in formation.3 I remember immediately wondering if blood money had contributed to the money I had just used to buy lunch. Suddenly my chicken salad sandwich became less appetizing. The recognition that the same religious order that brought Catholicism to this part of the country had chosen to treat human beings as property and were more concerned with economic evaluations than human dignity made me feel that the giants on whose shoulders I stood became noticeably shorter.

However, my pride continued to swell as we visited a small parish that used to be staffed by Jesuits. This parish had originally been founded because the black Catholics in town weren’t welcome to pray alongside their white sisters and brothers. A Jesuit, Horace McKenna, came to be involved with this new parish, which eventually culminated in significant involvement in the Civil Rights Movement.

When learning about the history of this parish from one of the women who works there, I was immediately struck by the continued vitality of the parish and the pride she and the other women involved there took in both the past and present of their community. And so I asked how long she’d been at the parish.

And then, there I was, speaking with a woman whose ancestors may well have worked on plantations just a few miles from where we stood at that very moment. And those plantations might have been owned by the same men who helped shape the Jesuit and Georgetown history I’d been spending all day feeling so proud of.

I was shocked. I was embarrassed. I didn’t know what to say.

While I’m reluctant to speak on behalf of this woman, it didn’t seem like she was blaming me for enslaving her ancestors. But it was clearly important to her that I, a Jesuit, know that we shared not only this conversation in the present, but the reality of Jesuit slaveholding in the past.

Meeting this woman has stuck with me ever since that afternoon in June of 2012. I’ve found myself carrying this question of how to respond to Georgetown and the Maryland Jesuits’ history of slaveholding into my prayer and my studies. A philosophy term paper, which required at least as much prayer as academic research, led me to conclude that I needed to become more responsible for the enduring legacy of slavery the day I enrolled at Georgetown University, and even more responsible the day I entered the Society of Jesus.

***

Over the last couple of years, Georgetown has taken significant steps in investigating and coming to terms with its slave-owning past. Much of the fruit of that work culminates today, April 18th, as Georgetown, along with the Maryland Jesuits, hosts a Liturgy of Remembrance, Contrition, and Hope and offers a formal apology for its slave-holding past in the presence of descendants of the former slaves. Additionally, the buildings formerly named for the Jesuits who organized the sale will be rededicated and named for one of the slaves sold in 1838 and a freed woman of color who founded a school for black girls in the Georgetown neighborhood.

These actions, while important, do not erase the grave sins of the past. However, if we have any hope of working toward a more just future we have no choice but to honestly and courageously engage the challenging and painful realities we find ourselves facing in the present.

It seems appropriate that Georgetown is taking these actions so shortly after Easter. When Jesus rose from the dead, the scars of his crucifixion didn’t magically disappear. On the contrary, Christ’s wounds became the starting point of reconciliation with Doubting Thomas. In the same way, our society still bears the scars of slavery and racism, and the only way we too can work towards reconciliation is by recognizing the wounds of those who continue to be marked by the legacy of slavery.

So what do we do about this “legacy of slavery” thing? Is that even real? Didn’t slavery end with the Civil War? And if not, the Civil Rights Movement certainly took care of any lingering racial inequality, right? Do we really have to spend time thinking and talking about this?

I think that seeing the on-going impact of slavery causes a lot of us to have the same reaction I had when the woman in Maryland told me she was a descendant of slaves. We get uncomfortable, embarrassed, and don’t know what to say. We want to look away. That seems, to me at least, to be an understandable initial reaction. But our reaction cannot stop there.

When the resurrected Christ appeared to Doubting Thomas, I’m sure Thomas felt embarrassed and uncomfortable. But rather than quickly looking away, he took the time to honestly look at and accept the reality of the wounds still evident on Christ’s body, even though the event of the Crucifixion was now in the past. The wounds were still there. The wounds are still there. We should follow Thomas’ example of not looking away.

Because we follow the wounded and resurrected Christ, we love and serve his wounded people. We know that the suffering and death of Good Friday must lead to the resurrection of Easter. Thus we should not and cannot allow the sins of our past to dictate the way we continue to act in the present and future.

Whether or not you can be present at Georgetown’s Liturgy of Remembrance, Contrition, and Hope, I hope we can spiritually join with both my brothers and the descendents of our slaves in remembering the sins of the past, expressing contrition for their impact in the present, and praying in hope that the wounded and resurrected Christ may help us build a better future.

Author’s note: Special thanks to Fr. David Collins, SJ for his work as the chairperson of Georgetown’s Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation, clarifying the historical details included in this piece, and introducing me to so much of Jesuit history, including this dark chapter.

***

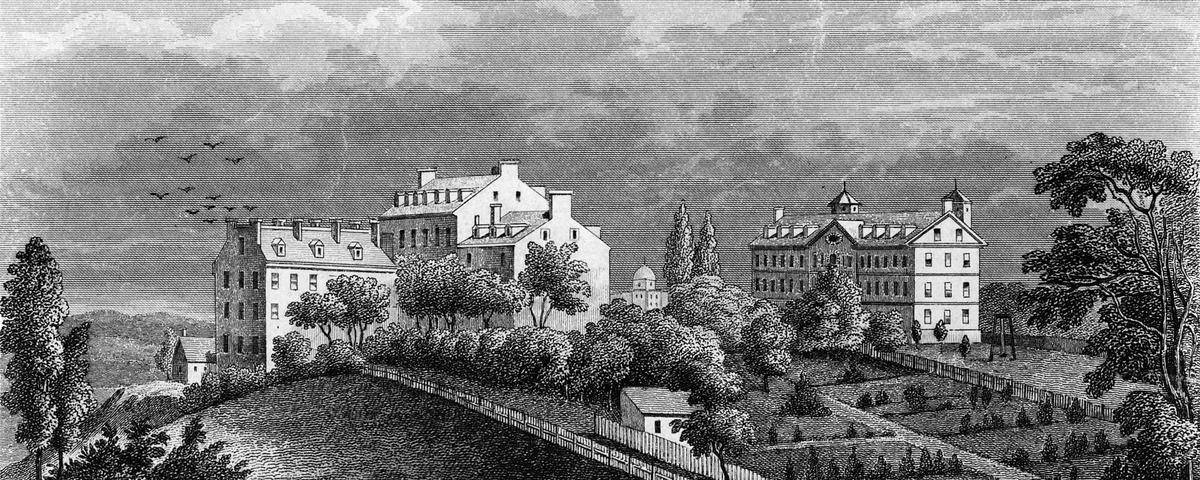

Image courtesy the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus.

- Those interested in a fuller account of this history should check out this timeline. ↩

- We also saw the graves of three young Jesuits who were killed when lightning struck the wire mattresses they were carrying across a field in the middle of a thunderstorm. It’s somehow comforting to know that mine isn’t the first generation of Jesuits to occasionally lack common sense. ↩

- Subsequent research complicates this picture, as the money from the sale arrived in small increments over the next twenty-five years and was mixed with charitable donations to the Society. Because the Jesuits’ philosophical and theological formation took place at Georgetown, young Jesuits would have clearly benefited. However, endowments or trusts were not used in the same way they are today, and so the seed money of the current endowment for Jesuit formation would not have come from the slave sale. Despite this, the idea of a connection between money from the sale of the slaves and my own financial situation remains a chilling thought. ↩