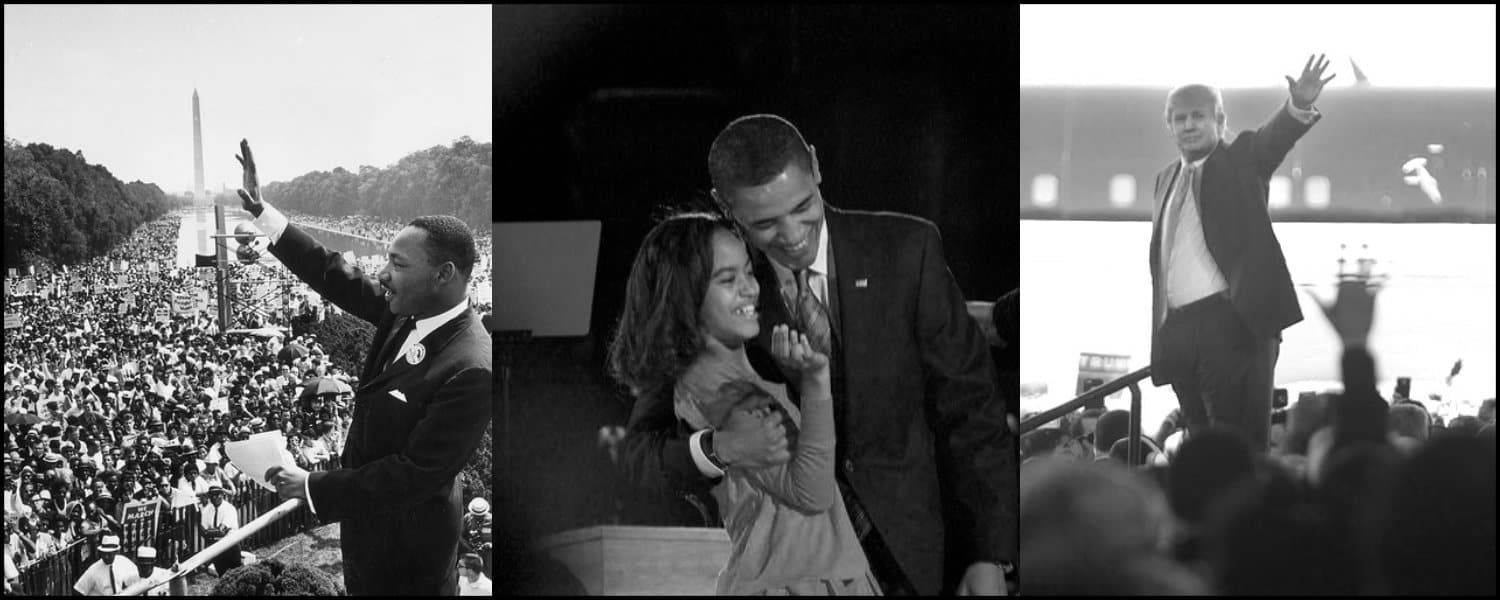

Standing before the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his most famous speech to over 250,000 people:

I have a dream that my four little children will live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

Every Friday before MLK Jr. Day growing up, my teachers in school would project a video of his speech for us to hear. I’d listen thinking that since racism is over, the speech was simultaneously inspiring and repetitive.

Admittedly, we’ve come a long way since 1963: for example, many people this week are thinking of November 2008 when our country elected the first African-American president, Barack Obama – with a wife, Michelle, whose family ancestry includes black slaves. For some, this signaled the end of racism in our nation.

And, on this day celebrating racial progress, many other people are thinking about our future president and his controversial racialized language during the campaign. Subsequent post-election accounts of racist acts suggest that perhaps we’ve made less racial progress than we thought. Both ABC’s television show Black-ish and this week’s cover of the New Yorker Magazine boldly highlight the still wounding legacy of American racism.

Certainly voting for Trump does not mean one is a racist person – one who hates other persons based on the color of their skin. That being said, each of us make assumptions and harbors prejudices about the people we interact with – including myself. These prejudices are implicitly formed by our conceptions of the great America – usually driven by the white heterosexual middle-class suburban version – shaped by a historical legacy of American exceptionalism, slavery, and Manifest Destiny.

Theologian Kelly Brown Douglass explicates this connection in her excellent 2015 book Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God. Explorers like Christopher Columbus “found”two continents full of people. But because these settlers saw themselves as ordained by God to “cultivate” and “civilize” the lands, they justified via “God’s will” the extermination of the Native population in today’s now US while also creating a labor force based in the enslavement of African peoples. This mindset infiltrated the consciousness of our Founding Fathers, too. When the land of the East was not enough, the Manifest Destiny narrative provided justification for more land seizures. Said another way, our great America was founded, already stained by the original sin of racism.

These personal biases – and the origin stories of our country – point to the deeper level of racism King addressed in his speech. Growing up we can’t help but learn these stories and incorporate them subtly into our understanding of what it means to be an American. We (the ones who benefit from the current racist power configuration) then end up making racialized excuses including:

- I didn’t own slaves so I’m not racist.

- I’m not racist, I have a black friend.

- Slavery is over so black people need to move on, and my personal favorite:

- Black people can be racist too. I am experiencing reverse racism.

Yes, in 2016 we do not own slaves. And sure, slavery is over in its 1850s version. It has, however, taken a new form via institutional racism: two examples include the prison industrial complex and neighborhood segregation.

And finally, while all people (including minorities) hold prejudices about other persons, Jim Wallis argues that racism is “prejudice plus power.” Racism is more than just implicit biases: it is the ability to use personal or institutional power and prejudice to deem some as less than equal – whether in school, court, communities, or the ideal of the Great American Society.

Were King living today, he would protest against the social fabric of our country. Take two examples from his speech:

“We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one.”

Sadly, despite the work of the Civil Rights movement fifty years ago, racial segregation continues to be a chronic American problem: “if you’re a black person in America, you’re more likely than a white person to live in an area of concentrated poverty,” the BBC reported just earlier this month. The consequence often means schools with less resources, worse housing options, and less access to financial credit. Women of color have higher rates of complications during childbirth. It also means that white and black persons are less likely to form friendships that could break down even well intentioned prejudices.

The liberal Northeast and West who voted for Obama perpetuate this segregation just as badly as the supposedly more racist Southern States. The difference is, in the Northeast and West, major urban centers tend to blame segregation on class, not race. But in reality, racialized social policies created many segregated areas intended to separate black from whites.

“We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality.”

Tragically, black people are three times more likely to be killed by police than white people, even if they are not suspected of any crime. And ironically, suggests The Atlantic, this is our system working properly: innocent young black men like Trayvon Martin are killed because our society “takes at its founding the hatred and denigration of a people.” The Atlantic concludes that we should expect more, not less, cases like Travyon’s because we are socializing ourselves to assume black persons are suspicious.

* * *

Let’s be honest with ourselves: racism is deep-seated in our country, and isn’t likely to disappear tomorrow. Our governmental structures, laws, neighborhoods, schools, culture, and personal consciousness are socialized by our racialized original sin. What is more, our current political culture suggests that decreasing housing segregation and preserving the social safety net for poor people will be difficult – at best. That being said, we aren’t helpless in the fight against racism. For those of us with privilege, we can start by deepening our understanding of racism – and our role in it. We can:

- Read and learn about racism: both published in 2015, Jim Wallis’s America’s Original Sin and Kelly Brown Douglass’s Stand Your Ground give comprehensive accounts of how racism has been with our founding. What they offer particularly is theological reflection that can help us choose to stand with God who stands with the marginalized.

- Watch film and documentary series about racism: this year’s Golden Globe Best Picture winner Moonlight addresses the intersection between race, poverty, and sexuality. Netflix’s 13TH examines the history of being African American in the United States – from slavery until today.

- There are excellent radio programs, too: BBC’s new “America in Black and White” tackles topics in depth including criminal justice and economic opportunity. New York City NPR affiliate WNYC has a new series too, called “Dear President: What You Need to Know About Race” to help educate with personal experiences of growing up marginalized.

- Perhaps most important of all: When we hear the experiences of black and brown people today who suffer from racism, it is understandable to feel defensive and “blamed” since we’ve benefitted at their expense. Admitting that to ourselves, we can listen more closely to the experience of our black and brown brothers and sisters so that real partnerships can be formed.

- Correct our friends when we hear racialized statements (like the ones above) that minimize the deep roots of racism and the privilege we’ve experienced as a result.

- Get plugged into undoing-racism trainings with organizations like Crossroads Antiracism Organizing and Training, and Whites Confronting Racism.

In his farewell speech to the American public last week, President Obama noted that race relations have improved over time, but issued us a call to work harder. That call means

acknowledging that the effects of slavery and Jim Crow didn’t suddenly vanish in the ‘60s; that when minority groups voice discontent, they’re not engaging in reverse racism or practicing political correctness; they’re not demanding special treatment, but the equal treatment our Founders promised.

None of this will be easy, none of it will be quick, and it will draw us out out of our comfort zone. Towards the end of his life, King famously said that “the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends towards justice” When we benefit from racism, we can remain comfortable with the status, or we can choose to participate in the arc of the moral universe. Choosing to participate means challenging the arrangement that makes our privilege possible. It means choosing to say, yes, we can.

***

Images courtesy FlickrCC users jrr_wired, thinairchi, and Gage Skidmore.