Despite Donald Trump’s Twitter protestations, Saturday Night Live has not settled for skewering Himself alone. Hillary got her share of ribbing. And this faux infomercial, The Bubble, fixes educated urban liberals in its crosshairs. If you haven’t taken a look, take a minute now:

A cheery voice calls to us: “Welcome to the Bubble! The bubble is a planned community of like-minded free-thinkers – and no one else!”

All are welcome to live in this utopia — which looks a little too much like Brooklyn — but the price of admission is comically prohibitive. A scruffy white 30-something assures us: “the bubble is a diverse community and safe space for everyone. We don’t see color here. But… we celebrate it!” His black friend winces uncomfortably, brilliantly. “So if you’re an open-minded person, come here… and close yourself in!”

* * *

The day after Donald Trump was elected president of the United States, many on the campus I am at looked like they had an existential hangover. In the week before election day, I was reading the work1 of a French thinker, René Girard, for a class on secularism. As I read about his theory of scapegoating, I saw how it was playing out on the American political scene. Societies – all groups of peoples – experience tension and discord, and the desire to restore peace requires identifying a destabilizing culprit — enter the scapegoat. This person (or subgroup), once identified as guilty, is sacrificed in the sure hope that the society can once again go on living in harmony. Because of the comparative civility of modernity, Girard reasons, we don’t permit grand spectacles of human sacrifice any longer – witch trials, public hangings, etc. But the dynamics of scapegoating have not gone away, they have just gone underground.

They have become, I submit, American politics. Up to the election day, the reasoning for many Americans went something like this:

All will be well in the country once Clinton wins her rightful place. Trump will be banished into political oblivion, a cautionary punchline. Then we can finally move towards unity and healing. Stronger together.

But then Donald Trump won the Electoral College, and the country has been roiling and convulsing since.

Girard notes that when we cannot easily rid society of a culprit, the thirst for assigning blame goes underground, fragmenting in sometimes ugly ways. Thus today individuals “do everything they can to conceal their scapegoating from themselves, and as a general rule they succeed. Today as in the past, to have a scapegoat is to believe one doesn’t have any.”

This last line struck me between the eye, since many commentators – and indeed about half of our nation – have spent the past weeks wondering how someone like Donald Trump could come to be elected president. Donald Trump, who has tapped support among rural, largely white, Americans. Donald Trump, who has publicly and vociferously scapegoated individuals (and minority groups, and entire nations…) for America’s problems. “When we suspect people around us of giving in to the temptation of scapegoating,” Girard writes, “we denounce them indignantly. We ferociously denounce the scapegoating of which our neighbors are guilty.” Indeed, in the past weeks many Americans have taken to publicly denouncing the president-elect and his basket of depl—er, cabinet prospects. But to what end?

I am not interested here in defending, or evaluating Trump’s choices since election. I am interested here in considering how people of good will should engage with people who voted differently. Girard cautions us against grand gestures of denunciation: “We could use our insight discreetly with our neighbors, not humiliating those we catch in the very act of expelling a scapegoat. But more frequently we turn our knowledge into a weapon, a means not only of perpetuating old conflicts but of raising them to a new level of cunning.” Our awareness of social inequities and inflammatory language causes a moral response of revulsion, and rightly so. But in the very act of attempting to correct a wrong, Girard warns, humans tend to employ the same ugly tactics.

“MOI?? I’m not scapegoating,” we tell ourselves. “I’m speaking truth about the racism and sexism I see perpetrated by Trump and his vision of America.”

But the good impulse to protect the innocent and the underrepresented, Girard says, subconsciously sends us on a quest for a new scapegoat. Hence we “practice a hunt for scapegoats to the second degree, a hunt for hunters of scapegoats. Our society’s obligatory compassion authorizes new forms of cruelty.” When scapegoating the leader does not work, we redirect anger at an other, mimetically — aping one another with the cruelty of mutual suspicion and impugned motives. This mimetic violence — mutually enforced aggression — is part of how humans interact in any distressed social group. All the more subtle, Girard says, when we feel certain of our moral superiority. An experiment right now: If you find yourself getting irritated and saying, “Yeah, but that is exactly what Trump supporters do all the time…” then you’re falling into the cycle of scapegoating that propelled him to power in the first place.

The breakdown that Girard describes is most dangerous when we do not recognize the hunt for what it is. We claim the mantle of unimpeachable moral clarity; whereas our opponents – Trump supporters – reflexively operate out of some Procrustean white privilege that feels threatened by women, minorities, etc. Indeed, media interviews with some folks at Trump rallies — and reports of subsequent hazings of minorities — have done little to disabuse us of that interpretation. But I have read many strongly-worded pieces in the past weeks — on Slate, the Guardian, the New York Times, Huffington Post, etc. — to the tune of “there is no morally defensible way to have voted for Trump, because to do so is to approve of his miscreant statements on [sexism, racism, xenophobia, etc.].” Yes, I have read all 282 of Trump’s disparaging Tweets. I understand his status as a loose cannon, at home and abroad. I share the frustrations and am genuinely uncertain about the future. To be clear – I would not, could not, did not vote for Donald Trump. But I also cannot, will not deny that there are legitimate issues that have attracted Americans of good will to vote for Donald Trump. My concern is when we conflate Trump’s words with his supporters’ reasons for supporting him, as if the two were coextensive. To do so is dangerous, because…

Drawing conclusions based on perceived motives is a fruitless, unfriendly game. I take as an example my beloved home state of Wisconsin. Wisconsin was one of the states not to go for Trump in the Republican primaries. It has gone Democratic every election since 1984, supporting Obama twice on his promises of hope and change. In the 2016 Democratic primary, Wisconsin went for Bernie Sanders, as one of many parts of the country that have witnessed economic stagnation and decline for the largely-rural working class.

Here is where things get interesting.

In the presidential election, the same counties that were Sanders supporters in the primaries came out overwhelmingly for Donald Trump. This came across as a surprise and betrayal to the Democratic party. But to read many election post-mortems, Trump’s upset in places like this was not attributed to the Bernie-lovin’ concern for economic stagnation among working-class Americans. Rather, the cause was something much more nefarious — deep-seated racism, fear of minorities, foreigners, and/or women, etc. Suddenly the ugliest aspects of Donald Trump’s rhetoric (sexism, racism, etc.) became the diagnosed reason for support of Trump, rather than one of the repugnant side-effects that voters made an uneasy peace with.

But do the facts bear this post-election narrative? Could not the economic plight, rather than racism and sexism, offer some explanation of Bernie-turn-Trump supporters? My reasoning here is speculative and not conclusive, I admit. But the limits of speculation is precisely my point — no commentators, save the voters themselves, can speak honestly about voters’ intentions. I am not exonerating – let alone defending – Trump’s statements. Yet we should be wary of diagnosing others’ intentions, for two reasons: 1) it flattens complexities in ways that muffle unpleasant truths. Wisconsin is a case study in the danger of overlooking raw data to fit foregone conclusions.

But also, 2) presuming bad motives of others only breeds mutual distrust (remember Girard’s mimetic violence?). By all means, we can and should challenge Trump on his public statements. But how we do so in a civilized society is important, as what has been done thus far has not born much fruit. Girard’s analysis about righteous anger and our thirst for a culprit is instructive: “The insight regarding scapegoats and scapegoating is a real superiority of our society over all previous societies, but like all progress in knowledge, it also offers occasion to make an evil worse. Let’s say I denounce my neighbor’s scapegoating with righteous self-satisfaction, but I continue to view my own scapegoats as objectively guilty. My neighbors, of course, don’t hold back from denouncing me for the same selective insight that I point out in them.”

This, Girard points out, is because humans, like all creatures, are mimetic. Monkey see, monkey do. You are questioning my good intentions? Well then…right back at you, pal.

This, Girard points out, is because humans, like all creatures, are mimetic. Monkey see, monkey do. You are questioning my good intentions? Well then…right back at you, pal.

[Click ‘unfollow,’ return to the Bubble.]

And so the world spins…fingers point across the aisle…hands wring within the party…and coastal fists shake at intolerant illiterati who pepper the countrysides… A few zinger interviews with a few racist Trump supporters suffices to dismiss the whole lot of ’em. The problem, then, is that all Trump supporters end up looking like Pennsatucky from “Orange Is the New Black.”2 Small wonder, then, that a few vociferous Trump supporters should respond with mutual distaste, perhaps even embodying the caricatured hatred that has been ascribed to them. Breitbart News did not, I submit, arise in a vacuum. And younger alt-right standard-bearers — like the trolling Milo Yiannopolis, and the white supremacist Richard Spencer — have been incubated in the same university cultures that champion safe spaces and identity politics. Are they repugnant to the mainstream? Yes. Is it surprising that they would develop in the modern political climate? Not at all.

* * *

The comparatively peaceful co-existence of different groups in America has set America apart from other nations and parts of the world. It is imperfect and incomplete, no doubt. But in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election, we realize that competing identity groups – the smaller communities we associate with and for which we have sympathies – have become something of an obstacle to national unity. Mark Lilla’s provocative opinion piece in the New York Times argues that the siloing into smaller identity groups has proven divisive. Doing some soul-searching as a Democrat, Lilla writes that

“Hillary Clinton was at her best and most uplifting when she spoke about American interests in world affairs and how they relate to our understanding of democracy. But when it came to life at home, she tended on the campaign trail to lose that large vision and slip into the rhetoric of diversity, calling out explicitly to African-American, Latino, L.G.B.T. and women voters at every stop. This was a strategic mistake. If you are going to mention groups in America, you had better mention all of them. If you don’t, those left out will notice and feel excluded. Which, as the data show, was exactly what happened with the white working class and those with strong religious convictions.”

In 2016, the American working class – largely white and without a college degree – found champions in outsiders like Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump. They have sought protection from economic downturn, poverty, drug and alcohol abuse, and high rates of suicide. This plea for sympathy rankles many urban, educated whites — particularly those of us who are loath to admit that history guarantees no people or nation unflagging success and stability.

The narrative of “white male privilege” — so often invoked as the root of all modern inequalities on university campuses and comment sections — can not neatly account for the rural white male, who is pleading for sympathy. We are left with a vague contempt for the proximate: “he should be doing okay in life, but he isn’t…and the fact that he looks enough like me makes it okay to dismiss his plight.” We can see how unnerving this is by seeing where our sympathies do, and do not, lie. We educated, liberal types go on service trips halfway around the world to encounter the other…but are less jazzed about visiting the working poor across town. We spend more for locally-sourced vegetables, organic breads and artisanal cheeses…and shake our heads at whites in poorer areas who “choose to shop” at Wal-Mart, the only store around for miles.

“The Wire” movingly portrays the scourge of drugs and poverty in Baltimore, and Black Lives Matter has awoken us to the plight of our African-American communities as they face violence with police. Yet are most of us educated urban types prepared to sympathize with a single white mother, whose son has PTSD after fighting in Afghanistan? We can laugh at the plight of “Drunk Uncle”3 on SNL, because who doesn’t have a down-and-out acquaintance like that? We roll our eyes at the goofy white meth-heads on “Orange is the New Black” and “Breaking Bad.” But we are not directed to feel sympathy for their plight. Instead we laugh at how they managed to squander the white privilege that their cultural betters didn’t. There is, nestled even in this negative image, some embedded expectations of what “whiteness” and “success” means. As Girard puts it, “scapegoating phenomena cannot survive in many instances except by becoming more subtle, by resorting to more and more complex casuistry in order to elude the self-criticism that follows scapegoaters like their shadow.”

* * *

I wish I had a neater end to these ponderings. I don’t really, other than to say that the socio-political landscape has shifted under our feet in unsettling ways. This is disorienting, and may well be for a while. But for many people, feeling unsettled is a daily reality. And unless you have the resources to move to the Bubble, we cannot settle for burying our heads in the sand. What should we do, moving forward? I don’t have answers, but I do have some thoughts.

1) We should recognize that scapegoating is cyclic and mimetic – and giving in leads to mistrust and fragmentation. If Girard is right about scapegoating, then the higher our perceived moral ground, the subtler our scapegoating gets. Searching for a guilty party to blame and denounce feels Twitteriffically thrilling – but accomplishes little. Public denouncements — like the flippant 3am tweets that prompt them — can become a defiant dodge from engaging people with whom we disagree. In our grand gesture of rectitude, we burn the chance to find a common ground with the other. As the philosopher Michael Sandel puts it, “to achieve a just society, we have to reason together about the meaning of the good life, and to create a public culture hospitable to the disagreements that will inevitably arise.” This means we refuse to engage in too-easy barbs and labels, even when they are lobbed at us. Even if — especially if — they come from the Tweeter-in-Chief elect. Baby steps, friends! But still…

2) In no uncertain terms, we must intelligently and clearly oppose the smoldering fringes of racism and sexism. But to do that, we must be ready to distinguish bona fide racism from people of good will whose concerns are not our own. Where children are ridiculed or belittled for being black, or Latino, or gay, or a girl, or Muslim — we adults must speak up. We do well to have students get to know different types of people from an early age. My parents sent me to diverse Montessori schools in Milwaukee through third grade, and I had friends there from all sorts of backgrounds. I wouldn’t trade that experience for the world. And – we also must teach our children to choose their battles carefully, to rise above the fray, and to defend themselves and their values when necessary. We cannot wait for daycares, high schools, or university classrooms to be spaces where ugly ideas are verboten, and bullying becomes extirpated. As this election cycle has shown us, the public square doesn’t come with padding, and attempts to silence fringe voices results only in more strident resistance. We must raise a generation of citizens with character, and we can, because…

3) We are all thoughtful captains of our souls. What unites us all is not our small-group identities, our language, or even the fact that we happen to reside in the United States. More fundamentally, we are all humans — sensitive creatures, equally (ir)rational, each with our own crosses to carry and emotional scars. Hillary supporters are complex individuals who made prudential decisions on election day; so, too with Trump supporters. We are a diverse country, and the world watches and learns how we do (or don’t) honor diversity in all its forms — racial, sexual, religious, as well as ideological. In the words of one commenter to Mark Lilla’s article, “the grandest and the greatest expression of diversity resides in the creativity, the character and the contours of an individual’s mind and animating spirit — not in the particulars of biology and body parts. We cannot move quickly enough away from thinking of ourselves as captives of our particulars, and towards a vision of ourselves as captains of our souls”4. I love that image – captains of our souls.

And before we demand civility from others, we might take a minute to think – how far do my sympathies actually extend? As Fr. Greg Boyle writes, “Here is what we seek: a compassion that can stand in awe at what the poor have to carry, rather than stand in judgment at how they carry it.” Who do I stand in solidarity with, and who is beyond my compassion? What group do I need to grow in understanding of? And finally,

4) Stay hopeful and engaged in the common good. Many friends from other countries marvel at how much emotional and mental energy we put into politics in the US. Thank God for the gift of life, and the ability to exercise freedoms, however imperfectly, in a democracy. Donald Trump may end up being a decent president, especially if he addresses the anxieties of those who did not vote for him. I am not holding my breath – but I remain hopeful. More importantly, we should be grateful that politics is not the only means we have of working out the common good. We have churches, community organizations, and educational institutions that minister to those most in need of our attention and support. As people of faith — Christians, Jews, Muslims, people of good will, etc. — let us bring light rather than heat to our national stage. And let’s all give time to our communities, rather than reading another too-long think piece about the dire state of America.

Life is for the living – so get out there, and be great, America!

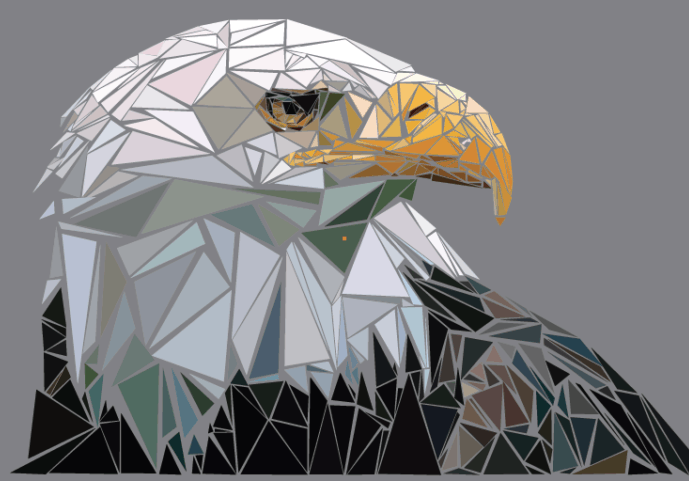

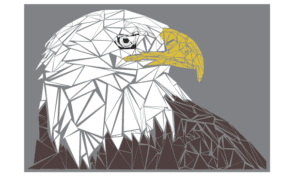

–//– Artwork of Fractured Eagles by Anna C. Simmons, used with permission from artist.