Frederick Douglass gave his famous Fourth of July speech a day late, on July 5, 1852. The majesty of his oratory matched the solemnity of the occasion:

It is the birthday of your National Independence, and of your political freedom. This, to you, is what the Passover was to the emancipated people of God. It carries your minds back to the day, and to the act of your great deliverance; and to the signs, and to the wonders, associated with that act, and that day.

There was only one problem:

This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.

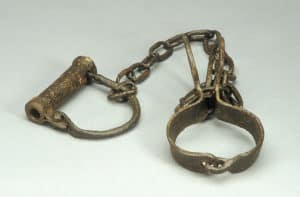

Douglass was referring, of course, to the fact that as an African-American he did not share in the rights of a U.S. citizen. As a former slave, he could also speak for the millions of African-Americans who were enslaved in 1852: to wit, a full one-seventh of the country. And so he could only mourn that African-Americans were denied the fruits of these “signs” and “wonders” that made Independence Day so miraculous.

* * *

Douglass asks the question that is now the speech’s title: “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” It is no surprise that he has harsh words:

The existence of slavery in this country brands your republicanism as a sham, your humanity as a base pretence, and your Christianity as a lie.

The Fourth of July is, of course, a day for honoring American independence. On a day in which many celebrate the virtues of the United States, Douglass sees fit to challenge it. And he is well aware that he comes off as boorish and impolitic. But these celebrations bring into sharp contrast the different conditions of the white and black American: “Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us.”

But if Douglass as an African-American had been denied the sight of such signs and wonders, it was not for his lack of faith. Indeed, Douglas had not given up on America. For it was clear to him that his vision had the U.S. Constitution on his side:

In that instrument I hold there is neither warrant, license, nor sanction of the hateful thing; but, interpreted as it ought to be interpreted, the Constitution is a GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT.

He excoriates the “republicanism”1 and “humanity” and “Christianity” of America not because America lacks those things, but because she has them and has abused them. A devotion to the true meaning of the Constitution, as opposed to the meaning that had proved useful for political and economic elites promoting slavery, would restore those qualities. Thus Douglass urges his audience to embrace its true meaning: “Read its preamble, consider its purposes. Is slavery among them? Is it at the gateway? or is it in the temple? It is neither.” Douglass challenges advocates of slavery on their own terms.

* * *

A reader in 2016 might wonder about Douglass impugning the “Christianity” of America. Indeed, Douglass’ harshest criticism is reserved for churches who support or tolerate slavery, whom he calls “the bulwark of American slavery, and the shield of American slave-hunters.” He writes,

Many of its most eloquent Divines, who stand as the very lights of the church, have shamelessly given the sanction of religion and the Bible to the whole slave system. They have taught that man may, properly, be a slave; that the relation of master and slave is ordained of God; that to send back an escaped bondman to his master is clearly the duty of all the followers of the Lord Jesus Christ; and this horrible blasphemy is palmed off upon the world for Christianity… These ministers make religion a cold and flinty-hearted thing, having neither principles of right action, nor bowels of compassion. They strip the love of God of its beauty, and leave the throng of religion a huge, horrible, repulsive form. It is a religion for oppressors, tyrants, man-stealers, and thugs.

Slavery has succeeded, Douglass concludes, because the truth of the Gospel has been perverted in the name of falsehoods that serve the desire for wealth and power. All of this Douglass condenses in my favorite line of the speech: “That which is inhuman, cannot be divine!”

Slavery has succeeded, Douglass concludes, because the truth of the Gospel has been perverted in the name of falsehoods that serve the desire for wealth and power. All of this Douglass condenses in my favorite line of the speech: “That which is inhuman, cannot be divine!”

* * *

But Douglass’ concern is not to indict America for her past, but rather to encourage her to take stock of the present for a better future:

My business, if I have any here to-day, is with the present… We have to do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present and to the future. To all inspiring motives, to noble deeds which can be gained from the past, we are welcome. But now is the time, the important time.

Douglass argues against nostalgia, for it leads us to mythologize the “good old days” and rest on laurels not of our own making. Douglass also seems to reject the kind of backward-looking attitude that is obsessed with revenge. Rather, in a quintessentially American move, he asks how we can move forward. This gives the speech a surprising note of hope, particularly at the end:

Allow me to say, in conclusion, notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country. There are forces in operation, which must inevitably work the downfall of slavery. “The arm of the Lord is not shortened,” and the doom of slavery is certain. I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope.

A former slave was not the most likely apologist for the American Revolution. Indeed, his criticisms are sharp. But, unlike many self-proclaimed champions of the Constitution, he read it. He allowed himself to be challenged by it, especially when everything in his experience had prepared him to hate it and reject it.

Today, of course, the Constitution continues to challenge us to examine where our ideals are not fully realized in our practices. And so, as we celebrate this Fourth of July in 2016, we might ask: how does the fourth of July challenge us to be a greater nation on July fifth — and beyond?

–//–

Title Image, “Happy Birthday America!” by Vinoth Chandar, is available on Flick here.Slave shackles image courtesy of National Museum of American History, available on Flickr here.

- By “republicanism” Douglass did not mean the American Republican party, but a government of officials elected by the people. As in the U.S. case, a republic is often a “mixed” regime, meaning it is part democracy (election by the people), part monarchy (headed by one leader, the president), and part aristocracy (represented by a small legislative body, the Congress). ↩