|

This post is an excerpt from the new The Jesuit Post book, The book features 20 new essays from writers for The Jesuit Post, as well as reprinting a few of the best essays from our first two years online. For more information, click here. |

|

“Do you see Jesus in me?! Do you?!!” The shout echoed in the bare room, less a question than an accusation. His eyes opened wide, nostrils flared, the pane of bulletproof glass and the intercom telephone in my hand vibrating with his anger. He was nearly twice my age and had spent most of his life behind glass like that, or bars. I added up the time once – he had spent more time in jail than I had been in school. I’d spent a lot of time in school.

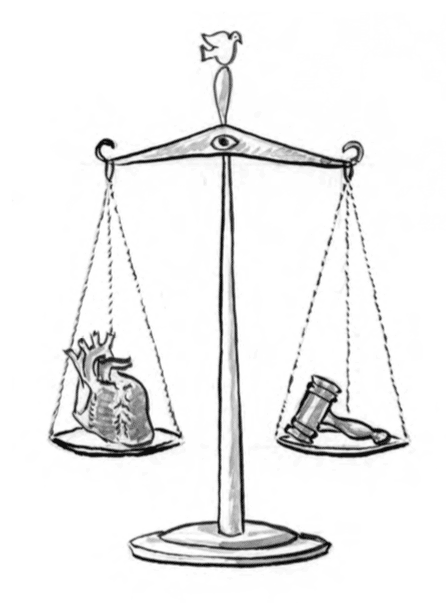

Truth be told, we frustrated each other. When I spoke it was about “the Law” (with a capital letter). In his blunt, obscenity-filled language he spoke about Life. When he talked I would try to filter out the profanity to get to the relevant stuff. He, though, wanted me to see that it was his life that was in the balance, and that his life was important. Mostly I just thought he was trying to be difficult. Undoubtedly he mostly found me condescending.

My mind spun as his question hung in the air, the tension making it hard for me to focus on what I’d come to the prison to talk to him about: his case, what had happened, what sorts of defenses he might have. I’d been doing criminal defense for a little over a year by this point, and I knew the relevant legal issues I needed to map – if he would just focus on what was relevant. He wanted to focus on what was important. “That’s really not relevant,” I finally responded. It was not the right thing to say.

Encounters like this nagged at me, but it took me a few years (years that saw me move from the practice of law to preparation for priesthood) to understand why. Now I think it’s not just that I was wrong, and he was right. I think it’s that he and I were speaking different languages, and that this difference reveals a fundamental tension in the law. After all, “the law” is supposed to remain pure, neutral, objective; precise. It never does. How can it when it has to be applied in the chaos of life?

For a long time his question haunted me. On good days, I put it in the back of my mind and just kept going. The other days, well, that’s when I prayed.

#

Knowing the “Law”

Image: Lane V. Erickson / Shutterstock

Everyone who’s watched Law and Order knows what “the Law” is. While being a lawyer or a judge seems to demand ever-increasing technical proficiency, “the Law” is something everyone encounters – if in no other way than through the dramas that litter basic cable. Short, sweet, and direct, “the Law” conjures for us a fixed set of ideas and principles. We know what law is and what it should do. It should promote fairness and create justice. It should preserve equality and encourage ethical behavior. It should vindicate the moral person.

And while this isn’t untrue, the Law is more than that, and less. I think that very often people like myself become lawyers and judges because we are mesmerized by the vision of a just world that the Law can represent. We study and think and write because of this beautiful vision we’ve glimpsed. But the more I practiced law, the more I looked at it day after day, the more ambiguous it became.

This is a common experience for lawyers, judges, clerks – all those professions that demand immersion in the clarity and neutrality of expression that define our sense of law. What many realize – what I realized – is that beneath the meticulous and exact surface of the Law lie sharp disagreements over what it means to be just or what fairness actually looks like. Even more, I realized that the law itself is ill equipped to resolve these disagreements.

#

Debate over the law has a tendency to become abstract. Very often when we speak of policy and politics, ideologies and ideals, we will quickly turn to broad terms like “freedom” or “fairness” or “justice” in order to understand better what is at stake. The thing is, most of the time we really don’t know what we mean when we say these words. Or, more accurately, even when we ourselves know precisely what we mean when we say, for example, “justice,” there are other members of our same society who mean something quite different by that word. The connotations with which we fill these words are sometimes so different, in fact, as to be almost perfectly opposed to one another.

This complicates things, to say the least, particularly when we want to reform the law or our legal institutions. We rely upon our society having a shared understanding of our ideals, and the words with which we describe them to one another, if for no other reason than because it’s these ideals by which we measure our laws. If it’s true that our society doesn’t seem to have a common sense of what “freedom” or “justice” means, then we have uncovered an enormous problem.

I don’t want to pretend to be the first to notice this problem. In fact it was Professor Steven D. Smith of the University of San Diego School of Law who first clarified this for me. Professor Smith has begun to call our inability to agree on the meaning of such words the “disenchantment” of our public discourse.1 Disenchantment is a great word for what’s happening, but not for the reasons we might expect. The term works well to describe the differences in the meaning of the words we use not because it meshes nicely with my own increasing disenchantment with the ability of law to create the just world it envisions. Neither is disenchantment accurate because of some growing cynicism in our society. And it works not because our language can suddenly only speak of mundane, technical things, or because our social and political conversation has the erudition of a fifth grader. Though all of that happens at times, of course.2

No, Smith calls the kind of public discussion we have in society today “disenchanted” because it is necessarily shallow. That is, the words we use to describe our social values are empty – my client and I could understand “fairness” to mean such conflicting things – precisely because this is the only way for a society as divided as ours to conduct a reasoned and reasonable discourse.

“It is hardly an exaggeration to say that the very point of ‘public reason’ is to keep public discourse shallow – to keep it from drowning in the perilous depths of questions about ‘the nature of the universe,’ or the ‘the end of the project of life,’ or other tenets of our comprehensive doctrines,”3 Smith writes. In other words, he thinks that “value words” have become little more than shells, hollow vessels that can hold whatever conflicting assumptions we want to fill them with. Even more, he thinks that we Americans lack the confidence to admit this, and that it’s this very refusal to see how deeply we disagree that prevents us from coming to any kind of consensus on how the law ought to help us live together.4

So, by disenchantment, Smith is not claiming that Americans no longer tell fairy tales. In fact, in some way he’s saying that we do nothing but – especially when we think we’re talking about the most important things. For Smith, the deep problem is that we use the exact same words to describe competing visions of what a just world is and how ours might become one, and that we are refusing to admit this.

#

My relationship with this client, it did not end well. Sitting in that cold and sterile cell, we glowered and we glared. We yelled and we shouted. And we parted on bad terms.

It left a sour taste in my mouth. I was not the person I wanted to be. Maybe I could blame him – he provoked me, he was difficult. But there was something else. That sour taste, it highlighted for me my discomfort with the practice of law and how we lawyers often approach our work. This discomfort spurred me into what I now would call discernment. Eventually, this and other discomforts would lead me to a deeper sense of my vocation, and to the Society of Jesus.

It was only after I’d been a Jesuit for some months – in the midst of making the Spiritual Exercises, the retreat that forms the heart of Ignatian spirituality and the Jesuit worldview – that I finally understood why it was that my client and I had parted so badly. Saint Ignatius begins the book of the Exercises with a small section of notes that precede the prayers themselves. These annotations describe the way St. Ignatius understood God to work with human beings and, in light of that, how we ought to relate to one another during and after making the Exercises. It was the twenty-second of these notes that opened my eyes. It reads,

For a good relationship to develop … a mutual respect is very necessary. … Every good Christian adopts a more positive acceptance of someone’s statement rather than a rejection of it out of hand. And so a favorable interpretation … should always be given to the other’s statement, and confusions should be cleared up with Christian understanding.5

For me, this simple invitation was transformative. It helped me to understand that what was lacking in me was a sense of humility in the face of other people. That, on a deep level, my experience of an event, an idea, a concept does not exhaust its fullness. And that when other persons share their different experiences, they are not wrong. It offered me a new way to approach the world. Disagreements and disputes could be places of growth only if I allowed myself to engage different ideas instead of simply seeking to win an argument. Not that there suddenly wasn’t a right and a wrong, but that who’s right and who’s wrong didn’t have to be my first question. Annotation 22 helped me to see that, before asking questions of right and wrong, I first had to ask another question: What do you mean by that?

For me, this simple invitation was transformative. It helped me to understand that what was lacking in me was a sense of humility in the face of other people. That, on a deep level, my experience of an event, an idea, a concept does not exhaust its fullness. And that when other persons share their different experiences, they are not wrong. It offered me a new way to approach the world. Disagreements and disputes could be places of growth only if I allowed myself to engage different ideas instead of simply seeking to win an argument. Not that there suddenly wasn’t a right and a wrong, but that who’s right and who’s wrong didn’t have to be my first question. Annotation 22 helped me to see that, before asking questions of right and wrong, I first had to ask another question: What do you mean by that?

This is what was going on between me and my combative client. We were saying the same words – “fairness,” “justice,” “law” – but we weren’t meaning the same things by them. And neither of us had ever stopped to ask. I remember all this dawning on me while I was making the Exercises and suddenly wishing I could do it all over again. Instead of hectoring him to focus on what was relevant, we could begin with mutual respect. I now wanted to give his statements favorable interpretations. Instead of presuming that I had the only right conception of what we meant when we said “justice” or “fairness,” I now wanted to bring my experience into an engagement with his. It was as if in my heart there was a clear ground for a moment, a clear point of mediation where our two experiences could be joined. I felt then that I could be an aid in that joining, help both of us see the import of the other.

And perhaps this sort of humility is what we, as a culture, need as well. A public humility. If Smith is right, it is clear that we simply don’t understand differing experiences of the same realities. “Freedom.” “Justice.” “Law.” We have become a people separated by a shared language. By the same words, even. One need only skim commentaries on law or politics to understand how this works.

What would happen, though, if we started by acknowledging this separation and then, rather than throwing up our hands at the emptiness of our language or digging even more deeply into our tired trenches, we put Annotation 22 into effect in our public discussions? What if we proceeded with a kind of public humility, by first trying to understand what it is that makes these words mean something different to so many of us? Could we talk to one another again then?

This does not require us to give up on our deeply held beliefs or our moral commitments. Rather, it requires us to recognize that, when we use words like “freedom” or “law,” we are using placeholders. That these are shorthand references to our experiences of these concepts. Already, we’ve filled them, consciously or not, with particular beliefs and commitments. Other people might fill them differently. We are invited, then, to engage, understand, and respect those differences, even while we might in the end disagree with them. We are invited, as Smith puts it, to a “conscientious engagement”6 arising out of a practiced public humility.

There are no guarantees as to the outcomes. We might not be able to reconcile our disagreements. Life is difficult and not everything will end well. But, like both my client’s life and my own, our story is not yet done. It took a personal humility for me to begin to imagine that my client and I were meaning different things, to wonder what experiences were filling the shells of the words we used, to even want to understand. Perhaps a public humility can allow us to rebuild our shared discourse on a larger level, to talk with one another again.

——//——

- See, Steven D. Smith, The Disenchantment of Secular Discourse (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010). ↩

- See ibid., 6-11. ↩

- Ibid., 17. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- David L. Fleming, S.J., Draw Me into Your Friendship: The Spiritual Exercises. A Literal Translation and a Contemporary Reading (St. Louis, MO: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 1996), 23. ↩

- Smith, Disenchantment of Secular Discourse, 224-25. ↩