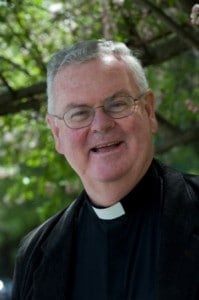

Daniel J. Harrington, SJ

Editor’s Note: Daniel J. Harrington, SJ, a leading New Testament scholar and professor at Boston College School of Ministry and Theology passed away on Friday February 7th. The following is a tribute by one of his former students.

The word “seminary” comes from the Latin word for “seed,” and the link between the two is fitting. Ideally, seminaries are seed beds that yield abundant crops of ministers to broadcast the Good News. For this to happen, the seed of the Gospel must be sown in the hearts of those people who aspire to become ministers, whether lay or ordained. Seminaries are places where this happens; places where sowers help produce other sowers.

The Reverend Daniel J. Harrington, S.J. – “Dan” as he is known to generations of his students, colleagues, and brother Jesuits – was a peerless sower. His death today marks the end of a stellar career in which he wrote over 50 books, hundreds of scholarly articles, and thousands of succinct abstracts of New Testament scholarship. I lived with Dan in a small community for three years at the Boston College School of Theology and Ministry. During that time, I came to see Dan’s scholarship as one of many ways he scattered very good seed in the hearts around him. But there were other ways he sowed, and other types of seed. And even with his passing, the church will continue to reap the fruits of his labors.

Dan sowed the seed of human formation. To use a word common in my native New York, Dan was a mensch. He ate ham sandwiches; he liked a drink before dinner; he loved the Patriots, Red Sox, and Bruins; he played goalie on BC High’s ice hockey team; he listened to sports talk radio; he drove a beat up Toyota Corolla; cook for the community when his name came up in the rotation; and he had a great laugh. All of that was just Dan being Dan. That’s the point: it was not only when he was lecturing or writing that one could learn from him; he taught even when he was being himself. Dan was a tutor in what it meant to be human. And that is what the church needs: ministers who are deeply human.

Dan sowed the seed of spiritual formation. Seeing him in our chapel before mass was like watching a sports fan get ready before a big game, or watching a film enthusiast do likewise just as the Academy Awards were beginning. Like them, Dan was right where he wanted to be, completely and totally at home. This doesn’t happen magically. For Dan, it happened over the course of a life spent sitting in quiet with the Lord – or sitting in an office while that same Lord, in the form of a student, comes in to chat. As a young(er) Jesuit, I know well the temptation to not sit, but rather, to stand, to move about, to do. But as Dan would remind me, the very first task Jesus gave his friends, at least according to Mark’s Gospel, does not emphasize doing: “He appointed twelve [whom he also named apostles] that they might be with him” (3:14). By wanting only to be with the Lord, by gladly sitting with the Lord, Dan was teaching us what it means to be spiritual. And that is what the church needs: ministers who are deeply spiritual.

Dan sowed the seed of pastoral formation. For virtually all of the 40-plus years he taught in greater Boston, Dan said Sunday mass at two local parishes: St. Peter’s and St. Agnes (the latter was his boyhood parish). On the one hand, Dan supplied those communities with mass coverage and extraordinary preaching. More significantly, however, those experiences supplied him with a connection to the People of God. He once told me that the quality of his scholarly work improved when he made the decision to take Sundays as days of parish ministry. No writing. No scholarly reading. Once I thought this was his way of taking a day off. I know better now: Sunday was the day he worked hardest because it was the day that he became a student of his parishioners. By coming out from behind his desk, Dan was teaching everyone what it means to be pastoral. And that is what the church needs: ministers who are deeply pastoral.

Dan sowed the seed of intellectual formation. Amid final examinations and papers one December, I mentioned that I had been distracted while studying that day, and that as a way of taking a break I had looked up some information about ThunderCats, a cartoon series I watched as a child. Puzzled, Dan turned to me and asked, “So you spent time today reading something about a cartoon from the 80’s?” It was devastating, but I recount the story to echo what one of his colleagues once said of him: “Dan has a thirteenth century monk’s ability to focus on something.” That’s right. He could read, write, and think for hours on end without being distracted. This was not a matter of being smart – which he was – but of cultivating virtues like concentration, dedication, thoroughgoingness, Dan was teaching everyone what it means to be intellectual. And that is what the church needs: ministers who are deeply intellectual.

Dan was fond of saying things like, “I’m the luckiest guy in the world: my job makes me read the Word of God every day.” Of course, all of Dan’s students would disagree with this, for we felt luckier whenever we walked into one of his classes. We were the seeds Dan was tending, and we were nourished by the seeds he was sowing. By ministering to us, Dan was teaching everyone what it means to be a minister. And that is what the church needs: ministers who are a whole lot like Dan.