Imagine an Olympic relay team made up of 20th-century Catholic writers. Walker Percy, Graham Greene, Evelyn Waugh, Flannery O’Connor, and J.F. Powers, among others, all show up to run for Team Tiber. An odd bunch, to be sure. Odd, because it’s hard to imagine so many writers who also had a penchant for running. Odd indeed, because the lady among them would have been limping from the lupus that maligned and eventually killed her. I’m sure, though, that it wouldn’t have held Flannery back from the race. Or from winning. Or from writing something ingeniously wry and macabre about the event after the fact.

This image is not odd in at least this respect: Many today look back at a generation of Catholic writers who, in spite of (or perhaps because of) their lack of religious resemblance to the majority, ran a powerful literary race that still draws crowds… And yet, there does not seem to be a new generation of Catholic writers to take the baton. Where have all the great Catholic writers gone?

Paul Elie took on this question for the New York Times in December, 2012. In his mind, the drought goes beyond Catholics and extends to Christian authors in general:

“[I]f any patch of our culture can be said to be post-Christian, it is literature. Half a century after Flannery O’Connor, Walker Percy, Reynolds Price and John Updike presented themselves as novelists with what O’Connor called ‘Christian convictions,’ their would-be successors are thin on the ground.”

The question is never as simple as writers and their talent, of course. New writers emerge. Many of them are quite talented. And a good number of these, presumably, are Christians. Why, then, do they not rise to the level of past greats? In response to this, Elie indicts a rising indifference to religion in secular culture:

“Where has the novel of belief gone? The obvious answer is that it has gone where belief itself has gone. In America today Christianity is highly visible in public life but marginal or of no consequence in a great many individual lives.”

So the seeming dearth of writers and writings of faith is only partly attributable to writers themselves. To use O’Connor’s well-known metaphor, authors are shouting, but their audience is only growing deafer by the day. Talented writers of belief can ply their trade with vigor, but they have little control over how receptive an increasingly secular culture is to religious viewpoints.

Still, Catholic writers keep on writing, and the conversation about their place in the larger, non-Catholic literary world continues. Just within the past month, for instance, Dana Gioia and Gregory Wolfe have published their own diagnoses and prognostications in First Things Magazine. Both are well worth reading.

The Jesuit Post wants to keep the conversation going. In our view, worthy runners are still showing up for the race. So in the weeks to come, we will feature contemporary Catholic writers who will talk about their work, their audience, and the specific challenge of being a Catholic writer in today’s America.

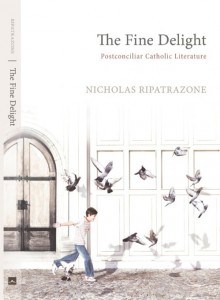

Nick Ripatrazone is our first featured author. Nick is a New Jersey native and writer of novellas, short stories, and poetry. This year, he published a collection of literary criticism called The Fine Delight: Postconciliar Catholic Literature with Cascade Books. When he isn’t writing, he keeps busy as a husband, a father of two, and as a teacher in public school and at Rutgers, Newark.

[Editor’s Note, 1/23/14: Nick has generously given us permission to reproduce one of his prose poems from Oblations. Scroll to the end of the interview to find it, or just click here!]

_________

JH: Thanks for the interview, Nick. First off, how did you get into writing?

NR: I started with Twilight Zone-inspired fiction in middle school, and continued writing on through to my 32 year-old present. I worked a handful of side jobs during graduate school (including garbage man, elections officer, and groundskeeper), and have taught public-school English for the past decade, in addition to college adjunct work. It feels natural to even out the day between writing (which feels like an internal, self-interested pursuit) and teaching (which, hopefully when done well, is focused on helping others).

JH: So, you kept your factory job.

NR: Sure. Both Ernest Hemingway and Andre Dubus stressed the need to break up writing with physical activity. It’s common sense, I think.

JH: You’ve written essays, short stories… You said you write “flash poems.” What are those?

NR: Ha! I was probably trying to be too clever with that designation. My first book, Oblations, was published as a book of prose poems (in the formal lineage of Baudelaire, Mary Oliver, and Russell Edson), but was blurbed, and sometimes reviewed, as a collection of “flash fiction.” I wasn’t thinking about genre when writing those pieces–I was thinking about form. Genre makes me think of content, and form is a visual, and possibly aural, designation. I wanted each piece to fit on the page. Something that could be read in under two minutes, that simultaneously felt complete but also opened toward more stories.

JH: What you said about a given piece feeling complete but opening up to more stories was definitely true in Oblations. That final section of the collection, by the way, shows a clear religious thread. Tell me about your history as a writer and your history with religion or belief. Where do they intersect for you?

NR: Belief and writing have always been united for me. They’ve never run parallel, never been separated. I think my ultimate literary fear is becoming what people might call, in the pejorative sense, a “devotional writer.” I’m devoted to Catholicism, but I also believe in the power of story, and I feel like devotional fiction is often lazy. Percy’s The Moviegoer is the perfect example of that. I’m not a fan of the epilogue, but that penultimate scene, where Binx is trying to figure out why the black man went to receive his ashes, that sums up my literary Catholicism: faith is blurry. Which is why Flannery O’Connor is amazing, but I also hunt for the Catholic glances in the works of lapsed writers (like the sarcastic and hilarious Thomas McGuane).

I’ve tried to carve out my own literary space. It’s been largely with secular publishing houses (Gold Wake, Foxhead Books, Queen’s Ferry Press), and a Christian press (Cascade Books). I’m a Catholic whose written for Esquire, and I’m a staff writer for The Millions, which is a secular publication on culture and literature with enormous readership. That’s where I want to be. Some writers hesitate to “out” themselves as Catholic. That’s fine. But I like the style of Kaya Oakes, Alice McDermott, Ron Hansen, Paul Elie, Gregory Wolfe, Brian Doyle, etc. People who are like “I’m Catholic. Now that it’s settled, let’s get started.”

JH: How far can particular religious values or themes come through in fiction before it gets “lazy”? What makes the difference between good religious fiction – even in a particularly Catholic sense – and devotional fiction, in the pejorative sense you mentioned?

NR: This was also a concern of O’Connor. I think the laziness occurs when the writer assumes that because a theological position exists that is articulated by the Church, that he or she can default to it, or reference it, rather than doing the dramatic work.

My real lesson in this idea was taught to me by Alice Elliott Dark, who was my mentor at Rutgers and a excellent fiction writer. She’s Episcopalian, and her not-quite Roman Catholic perspective was just the objective perspective I needed when writing fiction. When my new novella (This Darksome Burn) was still in the manuscript stage, Alice pointed out that I was writing from a dogmatic stance, not one of faith. Dogma doesn’t work in authentic fiction. Dogma is given to people, suggested, sometimes forced, but faith is the complicated, lived reality. We probably wouldn’t have many Catholics if identification required living one’s entire life–every moment–according to the Catechism. Hopefully good Catholics are shooting for everything, but we slip up. We need faith, not dogma. And the point is that God is watching us, but there’s not someone there with a chart, checking yes or no to each decision. The responsibility is on us. In the same way, characters in great Catholic or religious fiction need that free will.

This is probably why I like Catholic or religious fiction that unsettles me. The concept of Christ is an amazing thing–we should be unsettled, and then moved to act. Greene’s The Power and the Glory does that. So does “The Pretty Girl” and “Voices from the Moon” and “The Father’s Story” by Andre Dubus. Now that last story is exactly what I’m talking about.

So I guess I would say that devotional fiction feels too insular, too “finished,” too contingent upon assumptions of shared dogma. Christ came to shake things up like they’ve never been rattled before. So writers shouldn’t assume they can have it easy and expect to get people thinking and feeling.

JH: That reminds me – O’Connor wrote that “dogma is the guardian of mystery,” and elsewhere that “a story is good when you continue to see more and more in it, and when it continues to escape you.” It didn’t seem that, for her, dogma as such was an obstacle to portraying the messy or unfinished character of faith in fiction. Maybe it’s a question of how we tend to think of dogma… or maybe it’s a warning about presenting dogma too dogmatically.

NR: Yes, O’Connor was comfortable using the word and idea. Ralph Wood notes that she would often capitalize it–“My stories have been watered and fed by Dogma.”–but I also think O’Connor must always be thought of as a Southern writer, and an Irish writer, and, in the eyes of NYC publishing, a “fundamentalist” Catholic. So I wouldn’t approach dogma in the same way she does.

When I think of dogma, I think of the words “idea” and “doctrine.” Maybe I’m writing my own definition here, but when I think of faith I think of the words “image” and “mystery.” Now I’m really diverging from O’Connor, but I also think she was a bit silver-tongued herself. Take “Parker’s Back,” which is a story that contains a thesis–that iconography can be misinterpreted as idolatry by the fundamentalist mind–but is a narrative that creates the authenticity necessary through image and not idea. When I think of that story, images control my memory: Parker’s tattoos, attending that evangelical revival under the big tent, and, most clearly, him spending the night at the Christian Mission, the half-finished ink of Christ’s face on his back, in the glow of the phosphorescent cross.

Maybe O’Connor had that thesis in mind when she started the story. Or maybe she started with image (she was interested in tattoos, but from afar).

But we are talking about O’Connor as if she was some ordinary person. She was a once-in-a-century writer. The rest of us probably should be careful with dogma in fiction.

JH: I think O’Connor also provides a good segue to an ongoing discussion about the meaning and place of Catholic writing today. Musing on this question in “Mystery and Manners,” she said that the Catholic novelist doesn’t necessarily have to be Catholic. Speaking elsewhere, and probably more about how she herself approached writing, she said that “the Catholic novel is not necessarily about a Christianized or Catholicized world, but simply that it is one in which the truth as Christians know it has been used as light to see the world by…” What do you think? Does any of this resonate with this big question of what Catholic writing is for us today?

NR: It might be instructive to see how she leads into, and exits from, that quote. She prefaces it by saying that “all of reality is the potential kingdom of Christ, and the face of the earth is waiting to be recreated by his spirit.” She transitions from the quote you mention to a discussion of J.F. Powers, who of course was the most parish-centric fiction writer of recent memory. The sum total of what I think to be a difficult essay is, for me, that a Catholic novel requires God. Is that not the light she mentions? I’m worried that her discussion might be a bit circular here, but if I see the light as God, then it works. That seems like much the same way Percy approached Binx Bolling–the scene on the train, the ribbing by the aunt, those were all very “Catholic” scenes to me, although, as O’Connor says about Powers, real Catholic fiction might make Catholics uncomfortable.

The difficulty with Catholic fiction was summarized by O’Connor when she made the obvious assertion that one needed to be a “novelist” to be a “Catholic novelist.” Being Catholic is not enough. What makes me nervous is when Catholic reading and writing becomes an insular system, as if studying non-Catholics writers or thinkers will cause one to break out in hives. There’s nothing Catholic (or catholic) about saying the same thing over and over, and becoming complacent. Isn’t the point to bring people in the fold by hand rather than foot? To offer a Catholic possibility, so that people consider that it is a life worth living?

I think that as we move forward as Catholic writers and Catholic critics, we need to become fully part of the secular literary world without compromising our beliefs. The spiritual test is to write powerful fiction from a Catholic worldview that passes the litmus test of good fiction–so that the audience becomes wider, and that readers do not feel as if they can guess the ending from the first word. This was done by Greene and O’Connor, and is being done by Hansen, Brian Doyle, and others. In Catholic fiction, hope exists, but hope does not always win; in Catholic fiction, a sacramental vision exists, but it might not save troubled characters.

JH: So a lot of the things that make good fiction are what make good Catholic fiction – a sense of something hidden that slowly gets revealed, a reflection of reality as sometimes not ending “neatly,” with a hopeful note, or with everyone “saved” in the end. Maybe this points to how human good Catholic storytelling is: It embodies, in the particular language of free will and grace, salvation and perdition, hiddenness and revelation, some principal elements of good storytelling in general.

NR: Yes! The greatest story ever told, the Passion narrative, is so dramatic it brings people to tears. I suspect it’s because of the two levels–first, the intense drama of betrayal, of accepting punishment, of self-sacrifice to help others, and second, of course, the Christian feeling that Jesus did this for the entire world, which is the most humbling of concepts. That Passion narrative is violent, troubling, sad, splintered, and wild–but there is absolute hope. So, as you say, often Catholic fiction, or good fiction in general, doesn’t have nearly as much hope, but sometimes those whispers are enough. The end of The Power and the Glory, of Mariette in Ecstasy, those conclusions hit in the gut, and give the possibility of real hope and transcendence, whether it be in this world or the next. In this way, as you mention, the most un-Catholic thing to do would be to only hold the literary door open for Catholics, or Christians. It’s got to be open for everybody, and that includes non-believers. The best stories will draw people in–and, I think, the best of Catholic faith and practice, when properly and accurately represented, rings true as human and inspiring.

JH: Speaking of hope, there are some well-versed members of the writers’ community who are, let’s say, less than optimistic about the state of Catholic writing. What do you think is behind this pessimism? Are you equally as wary, or are you more hopeful about where Catholic writing is going?

NR: Sweeping generalizations about literature make for good ledes, but rarely survive critical examination. One paradox of Catholicism in the public sphere is that honest proclamations are taken as radical renewals; when Pope Francis says we must strike a “new balance” in representing “dogmatic and moral teachings,” he is calling for a return to the Gospels. The new becomes the old, which was the ultimate new, in Christ. Amazing–and inspiring, and, for me, evidence that people are hungry for the Catholic worldview in all of its permutations, and I happen to think that there are many Catholic writers out there willing to represent those struggles with imaginative fiction. In the spirit of Francis, critics should not be lining up Catholic writers for doctrinal judgment. I’m always fascinated by that biographical approach: writer A can’t be Catholic because he did Y and Z. Are people familiar with Graham Greene’s life? Do we really want to drop him from the list? Or is it better to see him as he was–imperfect, a sinner, but Catholic?

My reason for writing The Fine Delight was to offer evidence that Catholic literature is not only thriving in the present, but that its alleged splintering is in fact representative of post Vatican II cultural shifts and reconsiderations. The newer writers profiled–from Amanda Auchter (who just won the PEN award for poetry…go Catholic lit!) to Mary Biddinger to Brian Doyle (who is not really new, but only now are people really appreciating his incredible output–he’s everywhere, and has a new novel, The Plover, coming from St. Martin’s in 2014) to Anthony Carelli to Kaya Oakes. The conversation might start with Catholic fiction, but I think we want to bring poetry and non-fiction into the mix. Catholic literature is alive, and more than well. I’m excited to see what happens next.

JH: Sounds promising. So what do you make of the recent back-and-forth in First Things Magazine between Dana Gioia and Gregory Wolfe? Just to fill our readers in, both agree that the place for Catholic writing in the public eye has greatly receded in the last half-century. Gioia appears to put a lot of weight on the absence of writers to fill the shoes of past giants – Flannery O’Connor, Graham Greene, Walker Percy, etc. Wolfe takes issue with this, claiming that there is indeed a new generation of Catholic writers out there – but that for various reasons they’re not being heard. At various points, both seem to indict the culture at large as not being receptive to the kind of things that today’s Catholic writers are saying. Is this more or less how you read them, Nick? What’s your take – is there a problem here? And if so, is there a remedy?

NR: Gioia’s essay will become part of the Catholic literary curriculum from here forward. It is simply a must-read: comprehensive, controversial, and timely. But it also pissed me off. Here is where that happened:

“If one needs an image or metaphor to describe our current Catholic literary culture, I would say that it resembles the present state of the old immigrant urban neighborhoods our grandparents inhabited. They may still have a modicum of local color amid their crumbling infrastructure, but they are mostly places from which upwardly mobile people want to escape. Economically depressed, they offer few rewarding jobs. They no longer command much social or cultural power. To visualize the American Catholic arts today, don’t imagine Florence or Rome. Think Newark, New Jersey.”

Newark: where my family is from, where I went to graduate school, and where I teach (Rutgers). A punching bag for lazily generalists: a group I previously did not include Gioia in, and a place I refuse to believe that he belongs. He’s a California guy, so maybe this is a cross-coast misreading of a city pulsing with life (one, yes, burdened with crime and poverty–but what American cities escape those pains? And how are we being Catholic by reducing their populations to that?). That little quibble–and of course I know it is small–opened my eyes to a larger problem with Gioia (a problem I had with his 1991 essay, “Can Poetry Matter?”–well, had after the fact; I was 10 when it was first published). He’s got an idea of what Catholic literature should be, not what it is. He’s a dogmatist.

You know, Gioia is an incredible writer, a force of literary culture. He’s paved the way for Catholic writers and scholars to reach the high levels of publishing and academia, but he’s a different guy. We might share Italian ethnicity, but we’ve got vastly different tastes in literature. Pity the Beautiful is a gorgeous book–but it’s not from my bloodline. Gioia has, in one swoop, reduced the current Catholic literary presence to a footnote. He has ignored the great Catholic writing in small presses and literary magazines, not to mention the mainstream work. His sum definition of what makes one a Catholic writer–let alone a great one–is reductive and narrow.

Look at the first paragraph of his essay, which contains this absolute:

“Stated simply, the paradox is that, although Roman Catholicism constitutes the largest religious and cultural group in the United States, Catholicism currently enjoys almost no positive presence in the American fine arts—not in literature, music, sculpture, or painting.”

No positive presence. Donna Tartt, Donna Tartt, Donna Tartt. To name one person (three times). I get it–in a longform essay, you’ve got to take a stance at the start, and he knows what he’s doing with this essay. From Section VI:

“By now I have surely said something to depress, anger, or offend every reader of this essay. It depresses me, too, but I won’t apologize. If I have outlined the cultural situation of Catholic writers in mostly negative terms, it is not out of despair or cynicism. It is because to solve a problem, we must first look at it honestly and not minimize or deny the difficulties it presents. If we want to revitalize some aspect of cultural life, we must understand the assumptions and forces that govern it.”

There it is.

I read Gioia’s essay like it was a scolding from an elder. Which is cool. But it was his Bobby Knight moment. Sorry to mix metaphors, but we need a Lombardi, we need a Francis. Sure, Gioia is the guy to give a kick in the ass like this. I respect him a ton. But I’m more in line with writers like Wolfe, who I think have a closer pulse on the working writer, on publishing, and on, really, Catholics in the pews. Now there’s someone who is making writing of faith essential to a wide audience. And here I also stand with Dave Griffith — we need to be catholic in defining what it means to be a Catholic, literary or otherwise. Take David Foster Wallace, who was a seeker his whole life, who attended RCIA (but quit, I think, a few times). Gioia wouldn’t let him in the door. I’m going to be the guy to prop it open, to keep that adoration going past midnight, just in case somebody shows up.

The ultimate problem is that we are lacking a Catholic critical infrastructure. Gioia is right (and here he echoes Hansen) that Catholic fiction needs to do the hard work of faith, not simply “be” Catholic in intent. Without this critical infrastructure–without conversation and contradiction–we are left with a provincial literature. Catholic stories published in Catholic magazines for Catholic readers, or Catholic books reviewed on Amazon by Catholic reviewers who gauge the writer’s fidelity to Catholicism as you would rate a vacuum. I stay away from Catholic fiction written without a hint of the larger world, without a concern for craft. I don’t want to live in that literary world. I want to read a story that will stir a Catholic heart and pass the craft test. Devotion and discernment. Why can’t we have both?

An honest Catholic worldview is hard-won; it sees the world as suffused with mystery, but that mystery needs to be sought, and touched. We don’t need to bring God down from the rafters; I think He’s already here on the ground. We need a critical sense that proceeds with eyes open – the willingness to accept and recognize the various shades of Catholicism. We need to listen to women in this conversation, to lapsed Catholics and sometimes Catholics and not-Catholics. We need a dialogue. The ultimate remedy, though, is in Catholic writers. I say to them: Let’s prove Gioia wrong. I suspect that’s what he really wants.

Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe del Valle Pojoaque (from Oblations, Gold Wake Press, 2011)

Built 2001.

Washing of feet: twelve people lined behind the church. Three pieces of

plywood, side by side, holes in the center of each for draining. Hose pulled

out, faucet on. Khakis rolled to calves, dresses pressed against thighs.

Socks tucked into boots, lined in the grass like children’s backpacks.

Father Regan in sandals, sleeves pulled back to his elbows. White towels

on both his shoulders. This year there are three women. Father Regan

knew he would have to answer someone, whether it was a side comment or

a direct question: why the females? At first he would answer with a joke

(what man wouldn’t rather see the attractive feet of a woman than the

knobby feet of a man)? He would wash feet, pull his hand along heels,

dribble water along the tips of toes. And then he would claim permission

from the Holy See. Direct permission? Permission is never direct. Not

from God. Would all of us want to believe in so simple a relationship?