The act of naming and being named is a powerful tool of identification and power.

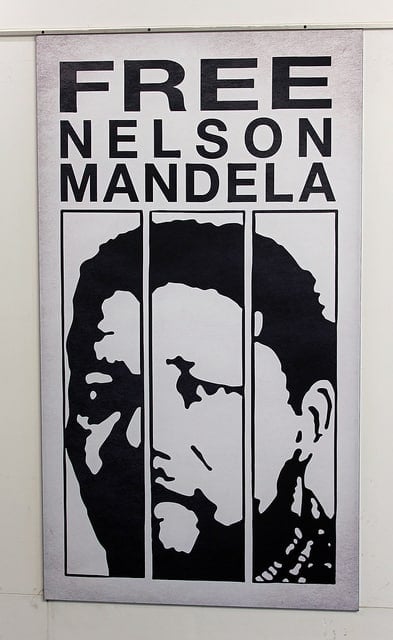

It seems obvious now, as we mourn him, that much of the world names Nelson Mandela a secular saint, that we name him reconciler, peacemaker; father of a nation. Less obvious, which is not to say less important, is the fact that, when he first entered prison, much of the Western world named him a terrorist.

Nor is the change from terrorist to saint the first time Mr. Mandela’s name was changed. In the first part of his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela wrote:

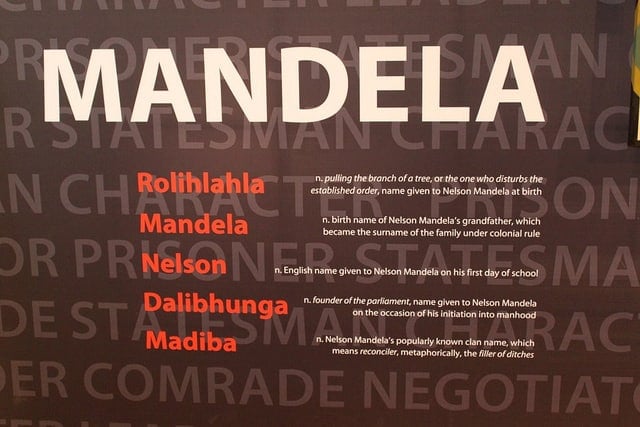

No one in my family had ever attended school…On the first day of school my teacher, Miss Mdingane, gave each of us an English name. This was the custom among Africans in those days and was undoubtedly due to the British bias of our education. That day, Miss Mdingane told me that my new name was Nelson. Why this particular name I have no idea.

His original name, the name his father had given him, was Rolihlahla, which means “trouble maker.” It’s the tension between this original, ironic name and his public, adopted name that, in many ways, mirrors the story of Mandela’s country.

***

Some we name as heroes and others we name enemies. Sometimes it is we ourselves who are given such names. But if names give us a way to identify ourselves to others, the lists we end up on perhaps reveal how others are looking at us.

How many of us, for example, know that Nelson Mandela remained on the U.S. terror watch list until 2008? It wasn’t until April of that same year — not even six years ago — that then-Secretary of Homeland Security Michael Chertoff said that “common sense” suggests his name should be removed. He went on to say that Mandela’s presence on the list “raises a troubling and difficult debate about what groups are considered terrorists and which are not.” Indeed it does. How does the world decide which freedom fighters to praise, and which to fear? Who gets named a hero? And why? 1

Two of Mandela’s speeches, I think, provide us with clues to these questions. The first came nearly fifty years ago, in his opening statement at the trial that would eventually send him to prison for 27 years. In this lengthy address Mandela explains why he was willing, ultimately, to resort to violent protest for the purpose of ending apartheid and achieving a free and equal democratic society. In the closing lines, by which the speech is best known, Mandela describes this as “an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.” Though he is now known as a peacemaker, Mr. Mandela’s most famous speech reminds us that the real story is more complicated. We cannot pretend that Mandela never endorsed — or for that matter never actively pursued — violence to achieve the just goal of human dignity. Mandela was a man who fought and endorsed fighting, when necessary, to achieve what he believed to be right. Troublemaking indeed.

The second speech that helps me come to grips with what makes for a hero is the one he gave upon being released from prison in 1990. In watching the speech one can sense a historical moment taking place, but was kind of historical moment is this? What did it signify for a world struggling to name this man accurately? Even more: Was it a transformative moment? Did the years spent in prison change his tone, his politics, and the means by which he sought his just ends? No. At the end of this 1990 speech Mandela quoted his own 1964 statement, saying once again,”But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.” Almost three decades later, Mandela remained as committed to his cause as ever. He was still willing to fight.

Which is not to say that nothing had changed. Because something had indeed shifted over the course of those 27 years even if it was not Mr. Mandela. What had shifted was the world; us. Mandela emerged from prison to face a world in which he no longer needed to resort to violence because his suffering, and his patient commitment to his cause, had already conquered our hearts and minds.

After 27 years what had changed was the readiness of of the tens of thousands listening to his words in person, and the millions around the world, to recognize and honor what he stood for. The world was ready to deem this man and this cause — the toppling of apartheid — worthy of being called heroic. Though he was undaunted, still willing to fight, the public at large considered him a secular saint. That phase of the struggle was over, though the work of rebuilding and reconciliation which would occupy the rest of his life had begun.

And it seems that Mr. Mandela knew exactly what had changed, and named a new role for himself in this changed world. He no longer needed to be a young militant pursuing a just cause. He could allow himself to be an old man, humbled by the years spent in prison, who wanted to serve the people. He said as much himself in the first speech he gave after being released from prison:

Friends, comrades and fellow South Africans, I greet you all in the name of peace, democracy and freedom for all. I stand here before you not as a prophet but as a humble servant of you, the people. Your tireless and heroic sacrifices have made it possible for me to be here today. I therefore place the remaining years of my life in your hands.

In this first speech Mr. Mandela named himself not a prisoner, nor the father of the nation, nor a rebel statesman, but a humble servant.

Attending to what, or should I say, to who has changed and who has remained the same in these two speeches reveal as much about us and our desire for a hero than it does about Mandela. And not only does it tell us that we are the ones who have changed, it tells us that Mr. Mandela, our collective hero, was and is a human being. This ought not be lost in the deserved praises being poured forth upon the sad occasion of his death.

***

The meaning of a name — that by which we identify ourselves and others — can change. Mandela went from ANC terrorist to freedom fighter to hero to servant to President to statesmen to secular saint in the span of a single lifetime. He was present, at the same moment, on the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners and FBI terror watch suspects. More than just a celebrity or even a revolutionary, Mandela became a global icon of the possibility of peace and reconciliation because of a belief that his life was to be lived in humble service to humanity.

At the beginning of the talks that eventually ended South Africa’s Apartheid government, Mandela reportedly said, “If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart.”2 The heroes we seek don’t just find the perfect words, causes, and strategies of reform. Often enough, that only leads to violence. The heroes we seek have a knack for breaking down our own resistances, for talking to our hearts, speaking our own languages; for changing us.

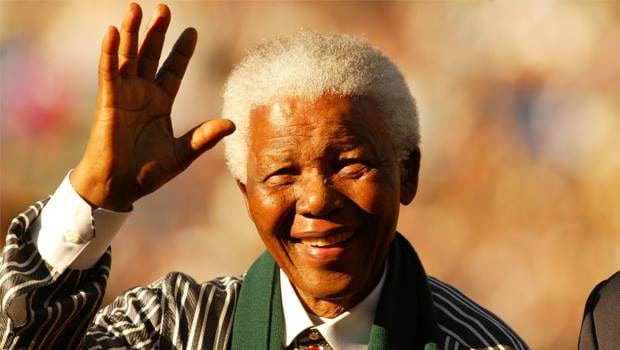

The Statesman — honored during Mandela Day at the UN, July 18, 2012

Photo by Flickr Creative Commons user Africa Renewal

Mandela spoke our language. By tapping into the human vocabulary of hope — of joy, reconciliation, mutual understanding, reaching the deeper meaning of those words which can so often seem banal — Mandela broke down our resistances. He changed us.

***

Nelson Mandela, who was imprisoned for 27 years for resisting white minority rule in South Africa, who served for five years as the president of the country, has died. This man has been known as Nelson, Madiba, Tata. Once named a terrorist, now he is named father of his nation, elder statesmen, humble servant.

As we remember this man of many names, let us not simplify him overmuch. No single name for him will tell his whole story. Instead, his story is about what he spent his life working for: a cause, a people, and a country — and a hope for them which he, as a humble servant, helped to bring to birth, and in the process changed our whole world, making it a better, freer, place.

— — —

- This is not an issue that has faded into the past, either. Just last summer, while making an official state visit to South Africa, President Obama compared Mandela to George Washington. The comparison was rather narrow and the president specifically observed the fact that both Washington and Mandela chose to leave the presidency instead of holding onto to it. Still, I wonder if England had had a terror watch list in the late 18th century, would Washington have been listed on it? ↩

- Today, South Africa has 11 official languages, which is relevant given that in South Africa’s history, language, or rather, the imposition of language, was often a tool of the government for control over the oppressed, and led to the Soweto Uprising in 1976. ↩