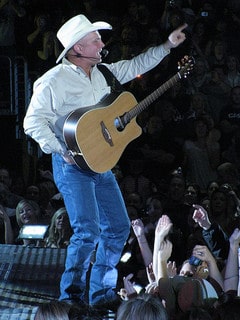

Charles Darwin, Jackson Pollock, and Garth Brooks. Admit it: this is an unlikely trio at best. What could a biologist, an abstract impressionist painter, and the best-selling country singer (and alter ego of alternative rocker Chris Gaines) have in common? None of their lives overlap; nor do their areas of expertise. But this seemingly random threesome can tell us something about randomness.

Charles Darwin’s publication On the Origin of Species in 1859 rocked both the scientific and Christian world. Over 150 years later, many Christians still struggle with his idea of evolution through natural selection. And as the token evolutionary biologist and Jesuit, in conversations, people often challenge me: “God could have not created the world through the blind, random process of evolution. Creation is too beautiful to be the result of chance. And I can’t believe in a God that creates through randomness.” Fair enough. But if we reflect for a moment on this challenge, we will see that it entails the following assumptions:

- Evolution is completely random.

- Randomness is not beautiful.

- God makes plans the way we do.

In fairness, and the spirit of charity, it’s definitely worthwhile to take a closer look at these assumptions to see whether there might be another way to approach this conversation. For too long, a certain kind of scientist (and Christian for that matter) has dominated the conversation about evolution. So the seemingly-random thoughts that follow here are my attempt to reframe this discussion using our unholy trinity of Darwin, Pollock, and Brooks.

***

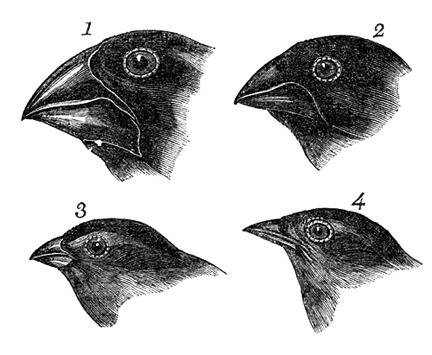

Peter and Rosemary Grant love Darwin’s finches of the Galapagos Islands. At least, I assume they do. After all, they’ve spent 40 years studying them. They’ve collected data on everything from their beak size to weight to favorite foods. This long-term data set allowed them to see evolution play out before their eyes. When the islands suffered a drought in 1977, natural selection changed the finch population, which initially consisted of mostly small birds. Before the drought, small, flimsy seeds were plentiful so small birds with small beaks did well in such conditions. However, during the drought, the few small seeds were quickly consumed, leaving behind large seeds with tough coverings. Large birds with large beaks that were powerful enough to crack these seeds were favored while smaller birds were selected against (read: they starved to death). The generation of birds that followed the drought consisted of, on average, larger birds.

Variation in finch beak size helped Darwin work out his theory of evolution through natural selection.

When the islands experienced an unusually intense rainy season in 1984-85, the number of smaller seeds available on the islands increased. Smaller birds were favored while the environment selected against larger birds with large beaks. These larger birds needed to consume more seeds to maintain their higher metabolic needs. Sure enough the finch population shifted so that the generation of birds following the rainy season consisted of, on average, smaller birds. So is natural selection random or not?

In dealing with these kinds of issues (as well as theological ones, like the humanity and divinity of Jesus), a Catholic often finds that the answer is not “either/or” but “both/and”. On one hand, natural selection acts in a predictable manner when the environment selects for (or, if you’re a pessimist, against) certain traits. On the other hand, the environment changes randomly. The favored trait during a drought may be selected against during a rainy season.

***

Evolution can also occur through mutations and scientists generally consider them to be entirely random. However, a recent experiment sheds exciting new light on this assumption. Scientists seeded a Petri dish with bacteria that swim with one tail and filmed them swarming over sugar and reproducing. Each day they selected some bacteria from the Petri dish and seeded a new dish. They repeated this for several days (bacteria reproduce quickly so that several days represents several generations of bacteria). After a few days, the bacteria swarmed 25% faster than their ancestors. When examined under the microscope the bacteria had multiple tails instead of just one. More tails made them faster.

The bacterium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, normally moves about with one tail.

The scientist reasoned that a mutation arose which gave a particular bacterium multiple tails. This bacterium could swarm faster and consume more sugar than bacteria with single tails. So the Petri dish environment favored these faster bacteria. But if evolution is completely random there might be more than one way to give rise to faster bacteria. If the scientists repeated the experiment, we would expect to see different kinds of mutations that gave rise to different kinds of fast bacteria. However, in 24 of 24 repeated trials, the scientists found the same mutation in the same gene!1 The evolution of these bacteria in the lab was very predictable, always giving rise to multiple-tailed bacteria. Completely random? Apparently not. Nature found only one way for these bacteria to become fast.

***

I’m no huge fan of modern art. A brother Jesuit and art historian once gave me a guided tour of Chicago’s modern art museum. I remember his emphasis on finding splendor in the random composition of lines and colors. He showed me how the arbitrary conjunctions of splotches, dots, curves and shapes formed something beautiful in each and every composition. After leaving the museum, I found “art” (or at least a new way of seeing beauty) in sidewalk cracks, rust marks on cars and shapes in the clouds, making me wonder why anyone would bother spending money on visiting a modern art museum!

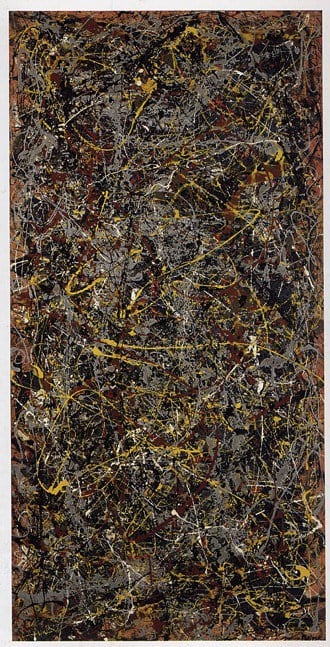

Jackson Pollock’s 1948 painting entitled “No. 5” ranks among the world’s most expensive paintings.

But I did find greater appreciation for modern art, especially that of Jackson Pollock. Utilizing the style of drip painting, Jackson Pollock relied on gravity to drip, splatter, pour and fling paint on a large canvas fixed to the floor to create something many people consider beautiful. Time magazine nicknamed him “Jack the Dripper” for his unusual style of painting. He describes himself as entering into the painting, using his entire body to paint. Read what he has to say about his technique:

When I am in my painting, I’m not aware of what I’m doing. It is only after a sort of ‘get acquainted’ period that I see what I have been about. I have no fear of making changes, destroying the image, etc., because the painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through. It is only when I lose contact with the painting that the result is a mess. Otherwise there is pure harmony, an easy give and take, and the painting comes out well.2

So he controlled some of the factors (paint color and type as well as his body movements), but many factors were outside his control (gravity in particular!). Both art critics and novices like me agree that this combination of random and non-random factors resulted in something truly beautiful. A 1949 headline in Life magazine suggested that he might be the greatest living painter in the United States. And Pollock believed that his method of painting was not as important as the statement his painting made: “It doesn’t make much difference how the paint is put on as long as something has been said. Technique is just a means of arriving at a statement.”

For Pollock, randomness is part of his technique. Like evolution via natural selection, Pollock creates something beautiful by relying upon both predictable and random factors.

***

Often my daily prayer devolves into a mental “to do” list as I think about what I want to accomplish in the following day, week, or even year. In my desire for control over my future, I make God my personal planner. I think most of us prefer predictability. We want to know where we’ll be in 5, 10 or 30 years from now. We want to know what job we’ll have and who are friends will be. We project these desires on our concept of God. God must surely know the future in the same way we “know” the future. God must have planned Creation in the same deliberate way I would plan ahead for the upcoming weekend. As though God has an elaborately constructed daily planner: 8:00am – breakfast with the archangels; 9:00am – smite an enemy; 10:30 – thunderstorm in Omaha; 2:00pm – answer prayers until dinner.

But this kind of planning places restrictions on who God is and what God can and cannot do. God is bigger than we are and we need to be aware of the dangers of assuming that God acts exactly like we do.

Besides, sometimes it may be better not to know every detail about our future. Garth Brooks echoes this sentiment in his song, “The Dance”:

And now I’m glad I didn’t know

The way it all would end

The way it all would go

Our lives are better left to chance

I could have missed the pain

But I’d of had to miss the dance

The song concludes that we are better off not knowing how things will end because, if we knew, then we may lose out on certain experiences. It shifts the emphasis of life from our obsession with the future to the present journey or Dance. And when I drop my desire to know my future with certitude and focus on the now, I find myself enjoying the “present” of the present and trusting more deeply in God.

***

Darwin challenges us to be more comfortable with chance and uncertainty and doesn’t make us accept complete randomness. His idea asks us to find beauty in the “cracks” and “spills” of a seemingly random life. It draws our attention to the present, inviting us into the Dance of life. All of these seemingly random thoughts can invite us into an experience of God that we may have never considered. When we let God break out of our box of preconceptions, we are reminded that God is bigger, more beautiful, and more surprising than we could ever have planned for or predicted.

***

The cover image is from alxhee available here on Flickr

— — — — —