Neon Outline

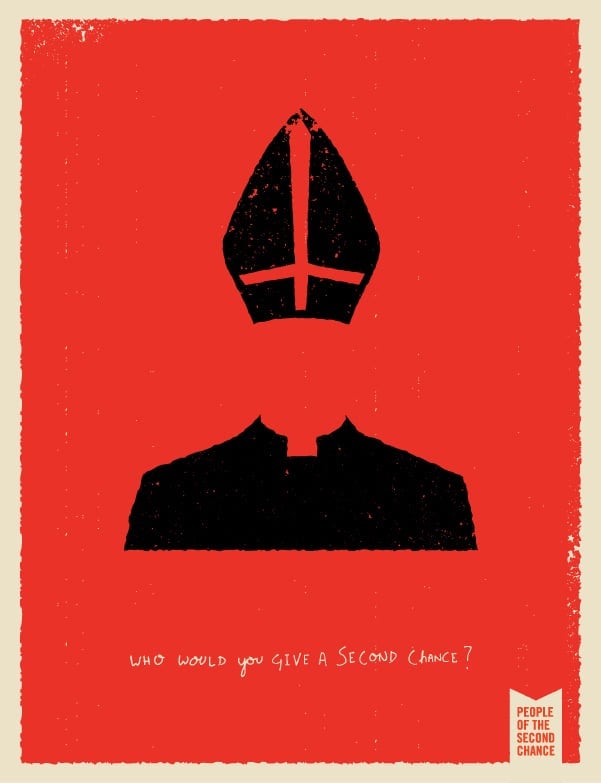

For about nine years I trained for the priesthood in the Jesuits. During that time I noticed that all books and films about priests follow one of five basic story lines. They are about:

1. A priest struggling on behalf of the poor.

2. A priest questioning the existence of God while fighting with a hide-bound, pompous and dictatorial bishop.

3. A young priest with careless bangs falling in love with a fetching and yearnful parishioner – who is possessed.

4. A priest whose homosexuality makes unreasonable demands on his honesty.

5. A priest with crisp diction and severe glances who is tragically uptight about religious doctrine and the finer threads of liturgical ceremony.

(If someone wanted to write a truly blockbuster priest story, then, it would have to be about a gay ghetto priest who teams up with a sultry devout widow to fight Cardinal Mussolini from shutting down Santa Las Causa. He impregnates the widow, comes out of the closet, loses the parish, wins the respect of the minority population, stays in the priesthood, pays for the kid under the table, finds out that the Cardinal is a real human being, garners his blessing to celebrate the pure Latin Mass in an abandoned warehouse, and in the end earns the only legitimate path to ghetto priest sainthood by getting shot trying to stop a gang battle stirred up by the very child he fathered who ends up standing over the holy man’s dead bleeding body, looking him in the eyes and suddenly realizing that this was the father he never knew, and that to atone for this he too would become a gay yet heterosexually libidinous and liturgically fascist priest one day, and it would start all over.)

There are also priests who write their own stories. When I studied philosophy at Loyola Chicago, I once picked up a non-fiction book from four decades back entitled, and I am not kidding, “I’m a Catholic Priest, and I Want to Get Married!”

While I think I’m as open-minded and reformish as the next guy, I had little sympathy for this priest who embodied Story Line Number Three and “Wanted to Get Married!” In fact, I was just completely annoyed by him. First off, his book, no doubt, gave him lots of radical cred that he just ate up. It was still, I assume, a new and sexy thing back then for priests to speak out against doctrine and authority on such matters. In 1972 I don’t know if a lot of priests were writing books like that. Either that or every priest was writing books like that.

Secondly, he irritated me because I imagined him as the priest who made quite a stir about his desires to his parishioners. Who ginned up loads of sympathy telling the lonely wives of St. Peter’s how he longed to “both celebrate the Mass and gaze in trembling delight at my wife in the front row. St. Peter had a wife. Why does this hide-bound and pompous church – which I love – crush the deep pulsations of my heart?”

He weeps. Wives swoon. Rosaries click. Popes are cursed.

Looking at his book, I wanted to say, ‘Fine, get married. No one is keeping you here, bro. LEAVE. You read the treaty accords before you surrendered. There was no mystery. Get over it or head out.”

But then again.

There were times in my formation when I too considered retrofitting the deal, or simply angling my way out. In fact, I once worked up a vast and unsinkable theological argument against continuing in the Jesuits. And against there even being a need for celibate missionaries period. It would lay down marvelous suppressant fire as I scrambled out of the religious foxhole. It is a highly sophisticated theory – and plan of action – that brings together the principles of Community Organizing, Post-Grad Volunteering, the National Guard, the Local Foods Movement, an extremely useful Catholic theological principle that declares You are Worshipping Jesus Right Now Even if You Don’t Realize it And/Or Believe in Him, the ownership structure of the Green Bay Packers, Springsteen’s “Atlantic City”, all of Protestantism, and another helpful doctrine: We’re all Going to Heaven Anyway, Right?

I can’t really flesh out this theory with all of its impenetrable arguments. Not only because it would demand more sources and footnotes than I am willing to supply, but because it could land me on some Vatican Watch List. I would then become a cause celebre for a certain type of fetching (well, maybe) and yearnful and eternally ticked off Catholic. And while I am extremely interested in being a cause celebre, I would rather be one for getting shot (but not killed and not too painfully) in the ghetto breaking up a gang fight. Not for something as run-through-the ringer as clerical celibacy.

***

Sand Outline

In a couple of weeks some guys I know are going to become ordained priests. They will become Jesuit priests. I have been, distantly or not, journeying with them for more than a decade now. Doubtless some have been through their own versions of the classic priest stories. Probably each of them has, at one time or another, worked up his own theological arguments for stealing away from his vows. Since we all entered as novices many of our brothers have left along the way. These new priests are the ones who have stuck with it – or it has stuck with them – and they are here and they are doing this.

We who live the vowed life sometimes can get a little self-pitying. We tell ourselves that The Secular Culture throws gleaming knives at the merest shadow of a cassock, making it very hard to be a priest or religious. The fact is it doesn’t. Not that much. We mostly make it hard for ourselves. Even though the image of the Worshipful Father of the past is mostly vanished, within the Catholic world a young priest or religious is still treated a bit like a crown prince. This is simply because there are so few of them. If you have a half-way decent personality, can connect with people, and bear even a shred of authentic humility, you practically will be carried on shoulders to donuts after mass.

And in the non-Catholic world, the vast majority of people out there, in America anyway, just try to be tolerant. At least on the surface, and especially about touchy things like religion. Those who would have some kind of disgust with your chosen creed or office are almost never going to share it with you out loud. Most people don’t like conflict, or don’t have the energy. They just want to get home and feed their kids.

But, having said all that, it’s not always a cakewalk, sticking with a religious vow (or any vow, I imagine), year after year. To be willing to be sent wherever you’re asked to go. To keep saying the old rites when so few people anymore really seem to care. To come home every night not to the honey scent of a chosen beloved partner but to some retired Coptic scholar/pinochle fiend assigned to your house two weeks ago who can’t seem to stop talking about “the old refectory at Viper’s Head,” whatever that was. To live and witness in the narrow, barely-travelled and sometimes hostile territory of the in-between – cultures, religions, nations, ideologies – where this order from its infancy was created to go.

These guys who will be ordained in ceremonies across the country (for the record, Stayer, Donovan, Magree, Noe, Ganir, Gilger, Surovick, Zipple, Scott, Kunkel, O’Keefe, Rogers, Butterworth, Navarro, Stephan, Stockdale, and Folan), they’re good men. They are smart, and kind, and relevant. They have a heart for the poor. But probably in any given room they are not the absolute smartest, kindest, or most relevant, or even have the greatest heart for the poor. Thank God. Who wants to be around people like that?

After nine years I switched from the priesthood track and became a brother in the order. A brother works for the mission outside church walls, using whatever comes to hand. Actually, most Jesuit priests work in the world too, along with the sacramental ministry which is their distinct mark. But for me becoming a brother meant simply being a Jesuit, and that was everything, and enough. I am glad some are still taking up ordained life, too. They are the men who are still here, the ones doing this. Trying to let their old lives grow a bit dark, so something greater can light them up. So Christ can be a priest through them.