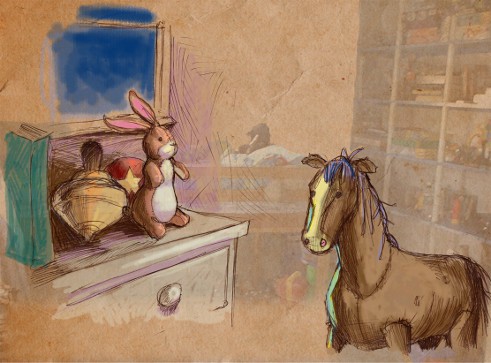

Velveteen Rabbit and Horse

On the second-floor of my parents’ house, where I grew up, there is a closet filled with books. All kinds of books. Old college textbooks, picture books, novels bought for entertainment on vacation, works of literature. Several shelves contain nothing but children’s books: Hardy Boys, Chronicles of Narnia, Lord of the Rings, Berenstain Bears. Growing up, I loved to read and re-read these books, hiding under my covers at night even though my father had told me to go to bed. In those hours, burrowed under my sheets, I fed my imagination on a steady diet of words.

One of those books, The Velveteen Rabbit or How Toys Become Real, bears the scars of decades of reading. The heavy cover is worn, its corners long ago worn away; many pages are torn and some even stick together on account of jelly residue left by sticky pointer fingers. The book, in short, bears as many traces of wear and tear as does the character about whom it is written.

The story is familiar to many: the velveteen rabbit, a Christmas stocking gift, becomes the favorite plaything. At first, the rabbit is a bit self-conscious: he’s not as shiny or intricate as the fancy, metal toys. Nevertheless, the boy comes to love the little rabbit and makes him his constant companion. And it is the boy’s love that makes the rabbit real: where the world would see only a ragged toy, filled with sawdust, gazing out at the world with dingy eyes, the little boy poured in love. And the boy loved not because the velveteen rabbit was the shiniest toy in the toy chest, but because the rabbit was his.

What comes next is no surprise: eventually, after spending constant vigil with the boy during a bout of scarlet fever, the rabbit is judged to be naught but a mass of germs, used up and unsafe, and so is dumped into a sack and slated for incineration. Old, worn, contaminated by its world, the doctor dismissively proclaims: “Get him a new one.”

“Get him a new one.”

In recent years, a steady stream of bad news has led many to take the doctor’s advice regarding not just stuffed rabbits, but the Roman Catholic Church. Very many of us these days – as news reports continue to inform us about the many indiscretions of Church (sexual abuse, financial cover-ups, issues with governance) and to remind us that our Church is no longer shiny and new – feel tempted to take the doctor’s advice, and consign the whole thing to thencinerator. We feel tempted to give up on a Church that seems worn and tired, infected with germs; beyond salvaging. Sometimes we just want to get a new one.

And not for no reason. Anyone who thought that anger toward the Church (particularly over the calamitous issue of child sexual abuse and its cover-up) would simply blow over in time clearly didn’t know what to expect. It seems to me, in listening, in talking to others, in feeling my own feelings, that the hurt and rage people feel arises from a sense of betrayal, a sense that the Church has failed to live up to its potential. It hurts so much because so much is at stake. So many of our lives have been tutored by the Church, from baptism to First Holy Communions to Confirmation, the Church has been a place where were prayed and played, hoped and feared. The Church’s women and men – priests and sisters, brothers and committed lay people – worked with us and for us, shaping us to be women and men for others. To learn that this institution, the very institution that encouraged us to be friends of Jesus, had so often and so recklessly betrayed His children… this leaves a searing wound.

“Get a new one.”

And a question: how can one be expected to love the Church, knowing what we know of it?

I have only one answer: we can love the Church because our love makes it real.

***

One night, the Velveteen Rabbit asks an old Skin Horse, “What is REAL?”

“Real,” the horse replies, is “a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real.”

The Church is real because it has been loved for a long, long time. It has been the place where many have learned about love: God’s love for us, our love for Jesus Christ, our love for our sisters and brothers. It is the place where the Spirit of love calls us to heal our broken hearts, feeds us at the altar, and encourages us to become what we receive: the Body of Christ.

It’s not only believers who admit such. No, the cynic and believer can agree on this much: the Church is real. The former might say, “The old girl had her day, now it’s time to ditch the old and embrace the new.” But even those call the Church real. The difference lies not in whether the Church is real, but in what reality means. And for my money, I’ll cast my lot with the little boy for whom reality was a thing to be caused by loving, the little boy who loved his rabbit not because he was perfect, but because he was his. Our rabbits are lovable not because they’re perfect, but because they’re ours. And the Church is ours. It’s been given to us and yet is held together by that which is more than us, held together, sometimes, in spite of what seem to be our best efforts to tear it apart.

This would all be well and good, apt for a Holy Thursday, if that’s all there was. But we ought not forget the remainder of the story. Wriggling free from the sack into which he had been unceremoniously deposited, the Rabbit looked out and shivered, having no longer a proper coat of fur. All of his memories rushed back just then, and the Rabbit’s sawdust heart broke with the question: “Of what use was it to be loved and lose one’s beauty and become Real if it all ended like this?”

It’s then, the story tells us, that a tear, a real tear, trickled out of the velveteen rabbit’s eye and fell to the ground. We know this feeling. But the tear isn’t barren, in the story it grows into a beautiful flower, and from its blossoms the a magic Fairy stepped. She gathers the old Rabbit into her arms and flies with him into the wood. There she kisses him and gives him to other rabbits to play with; live with. After a few moments, the rabbit knows even more fully what it means to be REAL. It means that he can sing and dance with the other rabbits, that at long last he can reach up and scratch his real nose with his real hind foot.

No one ever said loving the Church would be easy. Jesus certainly didn’t say it’d be a cinch, he promised only that the gates of Hell would not prevail (Mt. 16:18). Not a few of us have shed tears and, I believe, all of us await the coming of the Spirit to breath into all of us because we are the Church. Without question, to the eyes of the world we have lost much of our beauty. We are worn and tired and ragged. But the Church is a gift, our gift, and we receive it most fully when we’ve been loved and discarded, cried from loss and been given a community again.

We can love the Church because it belongs to us, because we belong to one another, because all of us belong together.

***

How will our Church’s story end? I ought to say “I don’t know.” That’s what I should say. But I believe, in hope now, that I do. I believe our own conclusion will be something like that of The Velveteen Rabbit, which concludes on a Spring day, when the Rabbit creeps out of the wood to have a “look at the child who had first helped him to be Real.”

Let us pray for such a Spring within the Church, for such a Spirit that can rouse the embers that smolder under scandal and embarrassment. As lovers of a real Church, we must decide: will we allow our Church to be judged solely by its tarnished past? Or will we have the courage to live a faith that others can believe in, a faith that washes the feet of prisoners, a faith that loves not perfection but Reality.

The cynic snorts, “Get real, Duns.”

I’m trying. Sure, the Church is a bit thread-bare at the moment. Its gilding has worn away, it’s dirty, it’s germy. There’s no doubt: the Church is very much real if, by real, we mean something that is not yet perfect. Just as the Horse told the Rabbit, becoming Real:

Doesn’t happen all at once. You become. It takes a long time. That’s why it doesn’t happen often to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept. Generally, by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joins and very shabby. But these things don’t matter at all, because once you are Real you can’t be ugly, except to people who don’t understand.

In this I find the courage, the freedom, and challenge to become real as a member of the Catholic Church. I don’t have to be perfect… I have to get real.

***

***

Saint Ignatius, no stranger to the 16th century Church’s shortcomings, counseled the young Society of Jesus to have just such an attitude. We ought to be those, he wrote, “who love the Church, precisely because she is covered with wounds.” And this because Ignatius understood that the Church was not meant for the perfect, but for the struggling, for those who fall frequently, even scandalously.

Ignatius’s words still ring across the centuries, they still challenge: have we strength enough to dwell within the real Church, the wounded Church? Have we desire enough to cultivate a real mysticism, one that’s able to abide the real rather than trying to flee into the non-existent perfect? Have we courage enough to say “I believe” in communion with fellow sinners, women and men who daily inflict wounds on the Church while still struggle to be conduits of grace in a broken world? Have we hope enough serve with joy?

A real-istic mysticism does not dispel the Church’s wounds. No, a realistic mysticism peers into the heart of darkness and waits with joyful hope. A realistic mysticism sees the pain in the dismissive advice to “get a new one.” A realistic mysticism works by pouring itself out in love not for the perfect, but for the broken. And this for a long, long time; until our pilgrim Church becomes real.