But all they want to do

is tie the poem to a chair with rope

and torture a confession out of it.

They begin beating it with a hose

to find out what it really means.

— Excerpt from “Introduction to Poetry” by Billy Collins

Early in high school, I made up my mind: I hated poetry. In those days, concerned with video games and sleeping, there was something about verse that offended my sensibilities. I had to read poems more than one time to understand them, and this seemed a waste of precious time playing Goldeneye. If I could have tied a poem to a chair, like Billy Collins suggests, I would have done so immediately. I often queried my mother (an English teacher by training): Why can’t they just say what they mean?! (For those who don’t speak fluent Adolescent, that’s translated: Why can’t this be easy?!)

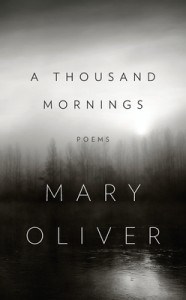

Turns out I’ve become something of a poetry fan since I graduated from high school a decade ago. What changed, you might ask? Simply put, I started reading poets I liked and understood instead of those inflicted upon me in British Literature. Once I realized that verse didn’t have to be drudgery, I actually starting looking for poets to read. And with some help from friends, that led me to the work of Mary Oliver.

If you move in any spiritual or religious circles, chances are you’ve at least seen a quote from one of her poems. For example, “Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?” Or maybe this one, always a favorite in Lent: “You do not have to be good. You do not have to walk on your knees for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting. You only have to let the soft animal of your body love what it loves.”

Oliver’s new collection of poems, A Thousand Mornings, was published by Penguin a week ago. I recommend it heartily: both to recovering poetry haters like myself, and to those who may still break into cold sweats recalling “Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey” from high school. Though I am tempted to articulate point for point the reasons why I love her work (and think you should too), her best advertisement for poetry is her own work. So I’ll get out of the way.

The following poem, which is in the new volume, appeared about this time last year in the New York Times, just as fall arrived.

Lines Written in the Days of Growing Darkness

Every year we have been

witness to it: how the

world descends

into a rich mash, in order that

it may resume.

And therefore

who would cry out

to the petals on the ground

to stay,

knowing, as we must,

how the vivacity of what was is married

to the vitality of what will be?

I don’t say

it’s easy, but

what else will do

if the love one claims to have for the world

be true?

So let us go on

though the sun be swinging east,

and the ponds be cold and black,

and the sweets of the year be doomed.