My wife and I both love the show and can’t wait for the next ones. I am 63 and my wife is 52. I can’t help but think how we would have done were we in our early 20’s now. Truthfully, it wasn’t much different. Similar mistakes and missteps but without “e” gadgets.

–Patrick C.562 from the Girls homepage on HBO.com

I want Girls to be a satire. It would make me feel better about liking it, and about the state of the world depicted in it. But Girls is not a satire, it’s a comedy. And that makes me slightly depressed. Neither is it comparable to Bridesmaids or The Hangover in anything but its raunchy humor. No, Girls is actually more akin to the late ‘80’s classic, The Wonder Years. It’s nostalgia and reverie. If The Wonder Years imagined the adolescent years of Baby Boomers, then Girls is imagining the wandering 20’s of the Bobo.

As a male critiquing HBO’s new series Girls, I feel as if I’m 15 years old again and about to pick the lock on my sister’s Hello Kitty diary. To read the diary might be exhilarating – and would be a gross violation of her privacy – but odds are I just won’t get it. Moreover, as a priest of the Roman Catholic sort, I am associated with a group that has recently been taken to the woodshed for its treatment of women. Any negative criticism might be seen as just another attempt to stifle the feminine spirit. So it’s with a judicious portion of caution that I offer a few thoughts on the show that has lit up the blogosphere.

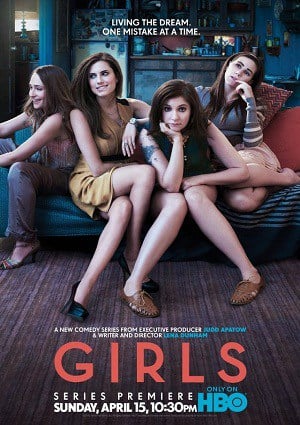

In Bobo’s in Paradise, David Brooks describes two privileged twenty-somethings, they are lost and confused, and yet boldly striking out on a great adventure. It makes for an accurate summary of the central dramatic dynamic of Girls. Shortly after setting out, Brooks writes, “they look elated, but then they become more and more sober, and finally they look a little terrified. They’ve emancipated themselves from a certain sort of WASP success, but it dawns on them that they haven’t figured out what sort of successful life they would like to lead instead.” What they are headed towards is not nearly as clear as what it is they are running from: their parents, the pressures of privilege, the burden of their own potential, and annoyances of received wisdom and ethics. Brooks might well be describing the four girls, Hannah, Marnie, Jessa, Shoshanna, who, according to the show’s tag line, are living the dream one mistake at a time. With each mistake come a few moments of stupefying, cringingly painful sobriety. For example, when Jessa’s boyfriend reads Hannah’s diary and turns it into a song that he performs in public, the show depicts this triangular moment of betrayal with all the nerves laid bare. It was hard to watch. I cringed for them in my living room. Yet this is one of the shows strongest elements, accurate and evocative depictions of the actual emotional damage caused when late-late-adolescents wield weapons best used by fully-grown adults.

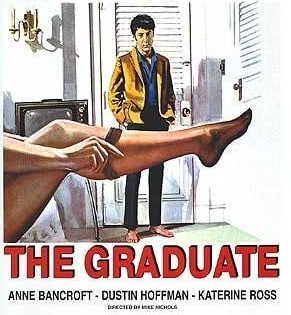

Although he might have been, in the above quotation Brooks is not describing Hannah and her gang of girls, but Benjamin Braddock and Elaine Robinson as they ride off into the sunset at the end of the 1967 film The Graduate. And this is the key to understanding Girls. As much as Girls wants to capture the contemporary escapades of thoroughly early-twenty first century wanderers, it is really a piece of nostalgia, a projection of self-expression, a bit of Bobo reverie. If you doubt me, then look at the tag line again: Living the Dream One Mistake at a Time. The question is who’s dream are we witnessing. I suggest that the show represents how Bobos like to imagine their twenties.

Notice Patrick C.562’s comment from HBO.com’s fanpage quoted above. Patrick is 63. He and his wife love the show not because it humorously depicts the struggles and concerns of the working girls of Brooklyn, but because it reinforces their own self-image. Actually, “reinforce” isn’t exactly the right word here. Girls does not reinforce Patrick C.562’s self-image so much as it creates a new one. It creates a self-image of what it could be like if he could be 25 again, right now, knowing what he knows at 63. It’s a projection from the height of middle age of what he imagines his twenties to have been like. And thus it’s a dream, not a reality, that Patrick C.562 celebrates.

At this point you may be wondering: what on earth is a Bobo? To understand why Patrick C.562 might want to project this dream back onto his own early-adulthood and thus edit his self-image for himself and Mrs. C.562 we better explore what Brooks is getting at with this neologism. Bobo is the combination of two words (bourgeois and bohemian) and is the product of Brook’s “comic sociology.” A Bobo is a paradoxical combination of some of the values of the 1960’s bohemian and some of the values of the 1950’s WASPish bourgeoisie. Bobos embody a free-spirited sense of self-discovery with an equally passionate drive for success, and they are the new elite, replacing the old elite that was based on family connections (think Rockefellers and Vanderbilts). They manage to wed a healthy dose of anti-authoritarianism to a strong sense of personal identity and personal success (think Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerburg). In short, writes Brooks, “dumb good-looking people with great parents have been displaced by smart, ambitious, educated, and antiestablishment people with scuffed shoes.” Bobos are wildly successful, and with success come the rewards of money and power. And happiness, if only their bohemian side would leave them alone.

However, the bohemian part of the Bobo’s split personality causes deep anxieties within the hearts of these new elites over their material success. In other words, “The sociologists they read in college taught that consumerism is a disease, and yet now they find themselves shopping for $3,000 refrigerators. They laughed at the plastics scene in The Graduate but now they work for a company that manufactures … plastic.” They must somehow “confront the anxieties of abundance” through strategies that give them a whiff of the bohemian patchouli. So instead of denying themselves their newfound elitism or shrugging off their antiestablishment leanings, they reconcile the differences (think Ben & Jerry’s or Facebook offering an IPO!).

To understand Bobo’s and their anxieties, Brooks suggests looking at their relationship with money. It’s complicated. In the Bobo world not all wealth is valued equally. According to Brooks, “in the 1950s the best kind of money to have was inherited money. Today in the Bobo establishment the best kind of money is incidental money. It’s the kind of money you just happen to earn while you are pursuing your creative vision.” The $500,000 dollars earned by a novelist of globally sensitive fiction is worth far more than the $15 million dollars made by a real estate tycoon. They want to give the appearance that money doesn’t really matter; in fact, it’s a burden. If they happen to make a zillion dollars selling subversive pints of ice-cream, then so be it, at least they have stuck to their bohemian roots. Of course to maintain the illusion that money really is not important requires quite a bit of cash. To maintain the balance of clashing values systems means that you buy a $900 hat that looks like it was worn by a struggling artist in 1920’s Paris. It means you go ahead and purchase the $3000 refrigerator, but you put it in a newly remodeled kitchen with wood floors salvaged from a 19th century French monastery.

Lena Dunham as Hannah Horvath

Lena Dunham, the 25 year-old creator of Girls, has clearly drunk the Bobo latte. Girls is the $3000 refrigerator of television entertainment, a tool used to soothe the restless bohemian spirit and reconcile the many facets of the Bobo persona. The show celebrates an atmosphere of bohemian caprice while shooing the bourgeois elements under the hand-knitted rug purchased from a recent immigrant in Union Square.Take Hannah, the character loosely based upon Dunham’s own life and played by Dunham. She’s a writer, but not a writer of novels or journalism, or even of poetry. Hannah is a writer of memoirs, and, of course, we are supposed to laugh at this. She has a very free relationship with money—she walks away from one job and will only take Bobo appropriate jobs. McDonalds, as suggested by a friend, will not do. She needs money for rent and a phone, but not that badly. The show desperately wants to create tension around the question of how will Hannah pay her rent, but this is the least successful element of the drama. It’s a comedy, after all; does anyone doubt that the money will appear. No lasting damage is done to any character in a comedy. And this is the Bobo mythology: we slacked our way through our twenties, and the just woke up one morning in our 30’s as President of HBO Entertainment. It was magic.

The truth is that Lena Dunham is a very talented writer and director of a well put together series on a network known for giving us high-quality entertainment. The sort of hard work and drive that goes into producing a show of such quality cannot be found among the characters in Girls. But to holistically portray women like Dunham would be to show too much of the bourgeois side of the Bobo. The Bobo agenda is better served by depicting girls in their wandering 20’s, still lost in the years just before their passionate and quirky individualism pays off. However, it strains credulity to think that characters such as these will end up with a hit TV show by the time they are 25.

In spite of pointing out all of the Bobo’s inconsistencies and silliness, Brooks is generally positive about the Bobo ethos and mission. So long as the Bobos can balance their two drives he thinks that they have quite a bit to offer American society. The danger comes when that balance is lost, and this is the problem with Girls and the slacker myth it adores. By hiding the bourgeois drive and determinism that balances the Bobo teeter-totter, the show’s creators suggest that through amoral, unprincipled wanderings one finds success, happiness, and, strangely, principles.