Following the lead of my brother TJP contributors Jim Keane and Jason Brauninger I start with a public confession: God was not my first love. No, I fell in love with nature long before my love affair with God began.

I’ve always felt free in nature, especially in the world of insects (and yes, of course I called them “bugs” when I was four). Ever since I can remember I’ve loved turning up rocks to see what was crawling around underneath. Flat rocks often revealed the best finds such as entire ant cities where industrious critters moved through their tunnels, carrying food and eggs, going about their utterly strange lives. I’ve spent hours looking for and capturing bugs in my backyard, and so it didn’t take me long to become familiar with sowbugs, fireflies, snails, ants, millipedes, centipedes, earwigs and beetles.

I learned some important lessons in the midst of learning all these names too. For example, I advise you from experience not place your prized ladybeetle, the one you were so excited to find gobbling an aphid on a rose bush, in the same glass mayonnaise jar as a spider. I still remember crying and feeling an odd mixture of sadness and anger, bewilderment and awe, when I realized what had happened. My four-year-old brain failed to understand why these two “bugs” couldn’t get along. “Wouldn’t they want to be friends in their new home?” I asked myself. Yet, the sight of the spider rolling up a ladybeetle inside its web and sucking out its juices completely captivated me.

My affinity for nature and the creatures that fill it grew as I grew. It continued in elementary school where I devoured nature books (I still have my tattered collection of Golden Guides). Science fairs, Boy Scout camping trips, and family jaunts into the country kept my passion alive. My interest in biology only deepened in high school at Cleveland Benedictine (yea, that’s right: Benedictine. Shh… don’t tell the Jesuits!) where my A.P. Biology teacher recommended taking a course in parasitology (the study of parasites) when I got college. Which of course I did. And my pursuit of a biology major at John Carroll University impacted my faith life in two different and unexpected ways.

***

When I arrived on campus to purchase textbooks for my classes I learned (to my great dismay) that the bookstore was out of the standard introduction to Biology textbook. I was near panic. How would I survive the next few weeks without the first textbook for the first class of my budding (and soon-to-be prestigious, no doubt!) biology career?! At eighteen, I took this as a disaster. I envisioned the worst: becoming a philosophy major (and ending up as the editor-in-chief of a faith and culture website). Fortunately my savior arrived, this time in the shape of my friend Mary who agreed to loan me her book.

A week or so later, I saw Mary at one of those student club fairs. She sat at the Intervarsity table and, figuring that it represented some sort of sports club team, I wandered over to thank her (for the one-hundredth time) for lending me her textbook – which, despite my worries, I hadn’t even cracked open. Seeing her JCU sweatshirt, I asked her what sport she played. She gave every freshman guy’s favorite reaction: laughter. To counter the blush rising up my face she quickly explained that Intervarsity was an interdenominational Christian group. It was then that she popped the question: “wanna come to our first meeting? And here’s confession number two: I wasn’t particularly thrilled.

Like many teenagers, I had cultivated a strongly cynical attitude towards matters of faith. But, I figured I owed her one, so I agreed to go. Funny how my simple yes led to four years of regular faith-filled meetings that helped shed years of built-up cynicism, and eventually bringing me much closer to God. But God still remained my second love; nature remained my first. It would take a second experience to change that.

***

Remembering the advice of my high school biology teacher, I enrolled in my first Parasitology class as a JCU Junior. For the first time in my academic life, I found myself reading a textbook for pleasure. I was fascinated by the ways parasites changed the behavior of their hosts, and I just knew that I had to continue studying this stuff. And so I went to The Ohio State University to begin a Ph.D. program in Zoology, which soon morphed into the Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology program (yes, it’s true, biologists like long names to make ourselves feel important).

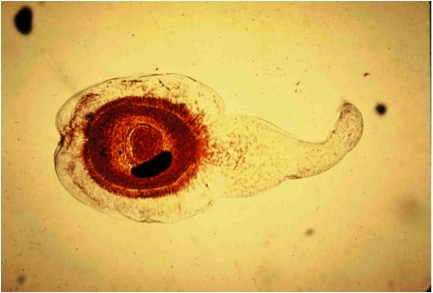

Odd as it may be to say, as I studied evolution and ecology my faith deepened and deepened. One way was through my study of parasites. I remember sitting in the lab one afternoon performing a routine dissection of a dead beetle – this one infected with tapeworm larvae (say “cysticercoids” if you want to feel important) – under a microscope. I was mesmerized by the fact that, when I sliced it open, there were parts of it still moving. The tapeworm larvae, completely dependent on its beetle host for survival, sloshed out of the beetle’s body cavity and into the Petri dish.

One moment this beetle-tapeworm complex was wholly alive and moving, the next it lay in pieces under my microscope. Like Humpty Dumpty, all the world’s scientists and all the world’s doctors couldn’t put this beetle together again. Deceptively complex, this simple critter led me to a profound sense of awe and wonder. I felt humbled.

It was a transcendental moment for me, a moment where I felt myself become acutely aware of something greater than all of creation. In my search for truth, I had the “experience of being grasped by a fullness of being, intelligibility, truth and goodness” and so had encountered Truth.1 It may be bold to say, but I’m quite sure that I’m not alone in this. I’m sure that so many of us experience these transcendental moments on the large scale.

***

Thank God that these moments didn’t disappear as I made my way through Jesuit formation, going from the novitiate in Detroit to philosophy studies in Chicago to Gonzaga University in Spokane to teach biology. It was at Gonzaga that I accompanied a number of my students on outdoor hikes via the GU Outdoor club. Gonzaga, located as it is in eastern Washington state, draws most of its student body from the most unchurched population in the U.S. Many of the students spend their Sundays watching sports or playing video games as opposed to attending Mass. Despite (or maybe because) they’re mostly unchurched, it was my experience that these students longed for something beyond them. When I would pray for my students I’d often hear in my heart Augustine’s famous line, “Our hearts are restless until they rest in [God].”

So exploring the scenic woods and mountains of the Inland Northwest brought some of these same students into contact with the beauty of nature. Many experienced the Transcendent as they felt grasped by something greater than themselves. And I think they knew this, even if they lacked the language to articulate their experience. One student, who I always thought of as one of those “spiritual, but not religious” types, surprised me by asking if I could help him find a priest who could celebrate Mass on their next Outdoor Club trip. I was so happy when he asked.

St. Ignatius teaches us that we can find God in all things, including nature. He teaches that the created things of this world can bring us closer to God: “All the things in this world are gifts from God, presented to us so that we can know God more easily and make a return of love more readily…”. Note that Ignatius is not saying that created things are God, but they can lead us to God. And the best of our current scientific research is confirming what Ignatius knew all along – that Creation is important for our spiritual well being. Take Richard Louv, who in his Last Child in the Woods argues that many societal problems (diabetes, obesity, attention disorders, depression, crime, etc) can be linked to what he calls Nature Deficit Disorder. Exposure to nature, especially during childhood, is critical for our physical, mental, emotional and spiritual health. Or the famous conservationist John Muir, who found spiritual healing in nature. He wrote of this way: “In God’s wildness lies the hope of the world – the great fresh unblighted, unredeemed wilderness. The galling harness of civilization drops off, and the wounds heal…”. I bet that Louv and Muir practiced something like their own form of Ignatius’ Examen as they found their hearts stirred in nature.

On one particular hike I was leading a group of incoming GU students (the group was called GOOB, and no I did not make this name up) through a modified Examen. I asked them at one point to reflect on the just-completed day of hiking, rafting and biking in the wilds of Montana. “Where did they feel God’s presence?” I asked. “Did they feel awe or wonder? Or maybe joy and consolation, energy and peace? Perhaps it was during a spontaneous sing-a-long with some friends on the trail. Perhaps it was while watching the sunset. Or maybe during a picnic while taking in the mountainous vistas.” Many responded that they had sensed God while quietly stargazing. Others said that they’d felt the Transcendent in the symphony of bird song and the colors of the wildflowers. A few, reminding me a bit of me, even found God in the insects.

— — — — —

- Haught, John F. 2007. Is Nature Enough? The Meaning and Truth in the Age of Science. Cambridge University Press: New York, p 215. ↩