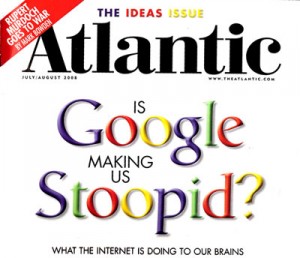

Several years ago, the cover of The Atlantic posed a provocative question: “Is Google making us Stoopid?” Nicholas Carr examined the possibility that recent technological advances have begun to change not only our relationship to information, but also the very way we think.

Several years ago, the cover of The Atlantic posed a provocative question: “Is Google making us Stoopid?” Nicholas Carr examined the possibility that recent technological advances have begun to change not only our relationship to information, but also the very way we think.

I thought at the time that it was hard to argue with that — and that was before I had a smartphone. In the not-so-distant past, dinner table debates proceeded with a certain amount of bluster, bluffing, and bickering. (“Well of course I know which U.S. president’s signature is on the lunar plaque!”) Today, matters of dispute are settled within seconds. “How many times has Meryl Streep won an Oscar? Hold on, let me Google it…” Whether or not Google is making us stupid, it definitely makes bluster and/or bluffing a precarious game indeed.

Beyond its effect on one’s conversational ego, a new study from the Pew Internet & American Life Project suggests that the benefits of our “hyperconnected” lives will come with certain costs.

[Millennials] will be nimble, quick-acting multitaskers who count on the Internet as their external brain and who approach problems in a different way from their elders.

So far, so good. But wait:

[T]he experts in this survey also predicted this generation will exhibit a thirst for instant gratification and quick fixes, a loss of patience, and a lack of deep-thinking ability due to what one referred to as “fast-twitch wiring.”

Ruh-roh. Damaged “deep-thinking ability” sounds pretty bad. And what about those parts of human experience — relationships with others and God, art, music, prayer — that are uniquely unsuited to instant gratification? Are we Googling our way to unfulfilled lives? But “just saying no” to Google is too easy, and likely impossible. The more difficult — and more important — question is how, in a hyperconnected world, can we still be truly connected?