Since I’m sure we’re violating a fundamental law of the internet by existing for two full weeks without linking to a video of an infant doing something cute on YouTube, I’m going to remedy that now. This baby, in addition to being cute, can’t figure out why print magazines won’t respond to her gestures and swipes the way her parents’ iPad does. It’s captivating, in an “Oh my gosh, how fast is the world changing?” way. I remember feeling like this when my youngest brother, 13 years my junior, got up in the morning and immediately went to the web instead of a newspaper to get the score of the baseball game that had lasted past his bedtime. (Or when, at four years old, he was confused by a faucet in an airport restroom that didn’t have an automatic sensor.)

So it’s cute — but the line at the end of the video has stuck with me since I first saw it. “Steve Jobs has coded part of her OS.” Perhaps it haunts me because it strikes too close to home: I’m one of those people with a Mac, an iPad, and an iPhone, and I’ve considered asking for an Apple Store discount because of the number of Jesuits I’ve advised to buy Macs. (Hey, if I’m going to get the tech support calls, they’re going to get computers that break less often.) As Eric noted last week, any tool we get too attached to has the potential to dehumanize us. Yet there’s something more than just the caution here — there’s the idea that the early and deep exposure to the iPad has changed the way this infant views the world and “re-engineered” her. Do these things really determine how I encounter the world?

What we spend time with, what we give our attention to, codes part of our operating system. And we can’t necessarily avoid it — you’re reading this on the web, after all, and there’s no bucket into which we can wring out the media saturation we all live with now. But there is perhaps reason for hope, because the “operating system effect” is not purely negative, and it can occur with prayer as well as with an iPad. During my thirty-day silent retreat in novitiate, after I stopped talking, and then after I stopped talking in my own head, I discovered something surprising in the silence. Beneath my interior monologue, the Psalms, drilled into me through daily prayer with the Liturgy of the Hours for the past five months, were whispering themselves to me. God had coded part of my OS.

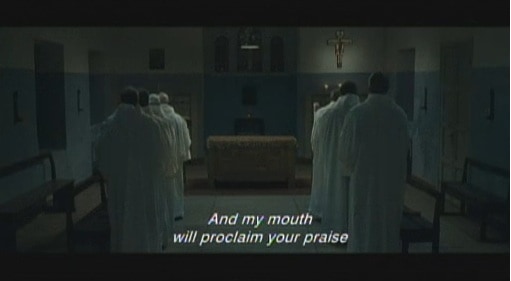

I’ll close with a glimpse of that better possibility, from the amazing Of Gods and Men, a film in which the the liturgy might as well be a character in its own right — and as Fr. James Martin, SJ explains here, the way prayer is woven through the film, and was woven through the monks’ lives, comes to transform them, and watching it with the right attention might begin to transform us, too.