I first ran past the work of Fabian Debora a few months ago. I’ve revisited it many times since.

I’ve never met Debora, but reading some of his interviews (try here or here) made the art even more alive, and made me realize how much I’d like to meet the man.

A native of the rough avenues of Boyle Heights in East L.A., Fabian Debora has seen plenty of dark days. He has stories to tell about gang violence, drug abuse, incarceration. But his art insists that God is here. Right here in the coarseness of its creator’s history, right here in the troubled avenues of Boyle Heights. Fabian’s art asks a pointed question: despite evidence to the contrary, can we still call this town the City of Angels?

His art also supplies a confident answer: You bet.

Debora finds the divine in the mundane – en su mundo – in his world. This is why he doesn’t just reproduce religious images from the past. Instead he updates them for his times, for our times, and in so doing joins generations of religious artists.

***

For centuries, artists robed the figures of biblical history in the garb of their own era and locales, even placing their contemporaries (often their patrons) in poses of prayer before that Virgin and Child who lived long ago even then.

It’s in this way that time, geography, and cultural boundaries bend so that the past can again meet the present. Thus the 15th century Flemish painter Jan van Eyck is free to depict Mary and the child Jesus in the robes of late-Renaissance royalty, and to place the then-living Chancellor of Burgundy, Nicolas Rolin, in front of them.

In My Virgin Mary in Relation to Tonantzin, Debora takes full advantage of the same license: he depicts the Virgin of Guadalupe as a “homegirl,” a female gang member. For Debora the Madonna dons hoop earrings and a blue hoodie, and stands gazing over a rich harvest of corn that grows beside the Boyle Heights Bridge.

Names canvass the bridge’s concrete arches – names that belong to Debora’s friends who were killed by gang violence. The upper-left hand corner of the painting is colorless and bleak, the urban decay standing in for Debora’s own past. But the fiery glory of the Virgin marks the vast majority of the frame; Debora’s dark past lies to her back while the brightness of his present and future lie ahead, held within the vitality of the Virgin’s gaze.

And for Debora the present day is nothing short of resplendent.

***

I look at these paintings, read these interviews, and I imagine that for every woeful tale, every memory of decay, that these days Debora could proffer just as many stories of strength and compassion.

Once he told his mother that she never should have had him.

Once, after a failed suicide attempt, he fled his mother’s house and into the city, injuring himself, almost getting run down by a truck on a highway. When he came to his senses, he called his mother and asked her to come find him.

Looking back, Fabian compares her trip to find him to the journey of the Virgin Mary, who walked to Golgotha to see her dying son on the cross. Both women saw their sons. They saw the blood. The humiliation. The bottomed-out, beaten-down and bare humanity of it all. “All that time,” he recalls, “my mother never gave up on me. She always tried to guide me.”

Days later he was in rehab. Within a year, Fr. Greg Boyle, S.J. was helping him start a new life.

Boyle, you may already know, is the architect of Homeboy Industries, a program that gives former gang members job training, education, and a supportive community. With help from his mother, from Fr. Boyle and others, Debora found a way to pull other gangbangers out of the dregs. Today Fabian himself works at Homeboy Industries as a substance abuse counselor and art instructor.

***

Given the experiences they’ve had together it is no surprise that Debora regularly names his mother as a constant an anchor in his life. Women, indeed, feature strongly in his story. He describes his grandmother as “the spine” of his family, and credits her with introducing him to yet another lady who’s held the title for the Most Powerful Woman in Mexico for almost six centuries: The Virgin of Guadalupe.

Get to know Mexican culture in any measure, and you’ll get to know her. Her image and story have a force for Mexicans and Mexican-Americans that no other figure can muster. Fabian remembers being a child and hearing his grandmother promise him that the Virgin would always watch over him. There’s no doubt that now, as a man, he fully believes it.

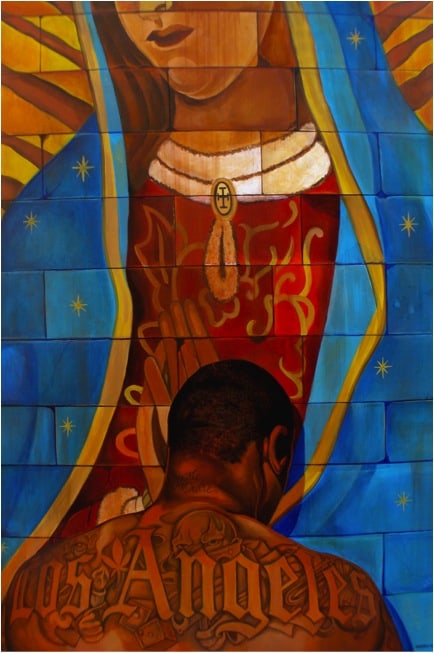

Debora gave this work personal title, Mi Madre/My Mother, it says. But the full title shows that Debora shares his Mother with an entire city: Mi Madre de Los Angeles/My Mother of Los Angeles.

Like so many of his ancestors and of his contemporaries, Debora’s painting depicts a young man leaning on his mother for help. His tattoos and scars tell a tale of a rough life. As for the Lady herself, her image lies not on a canvas but on cinder blocks – she presents herself in the grit of the city. The young man’s forehead rests on her clasped hands. The open fold of her blue mantle gives the impression that she’s about to enfold him it in as well, that the glorious Lady will wrap up the kneeling sanctuary-seeker in that sign of protection and patronage, comfort and safety. It was a gesture itself regularly imported into artistic depictions of Mary, the Refuge of sinners:

***

Debora’s Mi Madre is my computer’s desktop image these days. I find myself staring at it for minutes at a time. Is that a movement there? Does her mantle fall open to cover his painted shoulders? Do her hands unfold to touch the scars on the back of his head?

Debora’s life and art suggest that they already have. Indeed they have, are now, and in the future they surely will.