To date, I have had about eleven years of Jesuit education. High school, college, and graduate school. I drank the Jesuit ‘kool-aid’, and being a Jesuit has formed who I am and how I see the world. I expected that to continue now in my regency, teaching sophomores and seniors theology at Cristo Rey Jesuit High School in Minneapolis.

So…imagine the fear and mock outrage when I found out that our otherwise awesome principal was influenced not by Jesuits, but by the Benedictines and Christian Brothers.

Once my ego got over the fact that we would allow OTHER Catholic educators’ traditions into the school, I came to love the Christian Brothers’ preface that begins our all-school prayer each morning: “Let us remember that we are in the holy presence of God…”

Simple words to say. Hard to let sink in.

***

In my first post, I suggested that prayer affords us the ability to be more intentional in how we spend our time each day. Here I submit that true prayer allows us to contemplate our lives in a way that keeps us from becoming totally self-absorbed or discouraged by what we find. Allow me to explain.

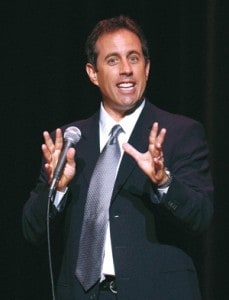

The great Jesuit preacher Fr. Walter Burghardt wrote that contemplative prayer is “taking a long, loving look at the real.” This makes sense, since the Latin verb contemplari means “to gaze at attentively.” A philosopher spends time taking a long look at the real in his or her contemplation of truth. I’d offer that some modern-day philosophers are observant stand-up comediansand cynical commentators of all stripes.

But contemplation in prayer looks a little different. For the one praying, contemplation involves a long, loving look at the real. This means looking at the reality of ourselves with patient love: love of our strengths and weaknesses, love of relationships, our desires, and of our hopes and fears. But how do we love what we find unlovable?

During my two years as a Jesuit novice (a “baby Jesuit” as my friends used to call me), sincerely desiring to grow in prayer, I confused praying with clear-headed philosophical contemplation. Oh, I was great at taking a long look at the real. I could assess all my faults with razor-sharp eyes (and, hey, how about everybody else’s while I’m at it?). The time I spent “praying” was actually more like the silent composition of a legal case against myself; a laundry list of failures and fears. I presumed that God would appreciate my candor so much, that He’d magically swoop in to remove these faults and replace them with a spotless, loving heart. So I “prayed”…and waited.

And waited.

And all the while I was wondering why my prayer – and perhaps even my God? – seemed so singularly unhelpful. The only thing I got out of it was that pit-in-the-stomach sinking feeling that the beautiful phrase “you’re a beloved child of God!” was just something we say to children to help them sleep at night. Anyone who has experienced spiritual desolation (a future post’s topic!) knows how this feeling creeps in.

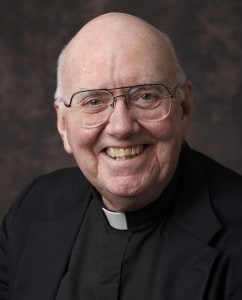

Fortunately, a tremendously loving Jesuit and patient spiritual director of mine, the late Fr. Tom Prag, said to me: “Joe, God is more patient with us than we are with ourselves.”

Simple words to say. Hard to let sink in.

***

In prayer, our contemplation of reality is a long, loving, look at the real. This interior posture is a decision, a cognitive choice to entertain the possibility that, in God’s estimation, perhaps we are more than the sum of our faults and limitations. The first letter of St. John tells us that God is Love. If this is true, then to put ourselves in God’s presence is welcoming a second opinion on our grave self-diagnoses. This shifts the goal of prayer from being a time of self-recrimination and navel gazing, to prayer as an experience of seeing every aspect of ourselves – our relationships, faults, desires; everything – as God sees us.

To be clear: prayer can certainly be a time to identify areas of growth and consider how sin works in our lives. But to do so without asking for God’s perspective reveals a distrust of God’s unconditional love. “Surely, God couldn’t love this mess… I sure don’t.” Lurking in there is that death-dealing assumption that we’d better fix ourselves up before we present ourselves to God. Isn’t it possible, however, that God sees our vulnerabilities and meager desires, and seeks to meet us right there? Could it be that a seasoned, loving Jesuit like Fr. Tom was right about God’s patient love?

As we go forward in prayer, let’s try to begin with that simple mantra of Jean-Baptiste de la Salle and his venerable Christian Brothers. It took this young Jesuit a while to do so, but… Let us always recall that we are in the holy presence of God.