One night about two years ago I witnessed one of the most brilliant moments of bravado and practical group-think I had ever seen. I was at an Occupy protest in California when a 40 year-old man, trying to look twenty years younger than he was, stood up in jeans and clunky glasses. As he peered out from behind hair just long enough to be considered hip, surveying the assembled throng of young occupiers gathered below, he carefully chose his words. “I was not born a revolutionary,” he began, “I became a revolutionary twenty years ago on those steps right over there. It was here, on this campus, Cal Berkeley, where I first heard the words of revolution spoken from…”

At this point, he was quietly interrupted by a tall man in jeans and a T-shirt who came towards the revolutionary and mumbled something in his ear. He then gently reached for the microphone. The revolutionary paused for a moment and looked down at the mic before reluctantly surrendering the talking piece. The man in the T-shirt placed the microphone to his own mouth and said, without a hint of either judgement or apology, “Hey, uh…I know that emotions are pretty high right now and we all have some things that we might want to say. But this isn’t really the time for impassioned speeches. There are a lot of people who need to talk, so try to keep your comments focused on events that will be occurring over the next week. Thanks.” He passed the microphone to a young woman who reminded people of a meeting about the coming worker assembly down at the Oakland docks. The rest of the session progressed without dogma or drama and the night fizzled out (not unlike public rallies like Occupy and Tea Party). Viva la revolución…

***

What we saw in movements like Occupy and the Tea Party was a call towards collective change. The proposed formula for these groups:

Political ideology + social action = transformation of culture.

As we can see by watching the ways that these various movements rose and then declined in popularity, there was a difficult tension at play.1 On the one hand, ideology that does not involve action will fail. At the same time, if there is not a unifying ideal, the actions will become disorganized and eventually fall apart. There is a certain difficulty that the secular imagination has with articulating a coherent narrative capable of bearing the hopes and dreams of North Americans.

According to William Lynch in Christ and Prometheus, the secular imagination, when working at its best, relies on the assertion that scientific belief can stand on its own without any need to reconcile it with a religious narrative. For example, there is no deeper meaning necessary to understand the beauty and power of atoms. A healthy imagination is not characterized by limitations, it is characterized by freedom to imagine possibilities and base belief on corresponding evidence in the natural world. The development of knowledge can lead towards an agreement that our shared humanity is enough to create a shared will. The secular mind finds its imagination growing stronger in a world where reason, trial and error, and fact open us up to knowledge of the cosmos.

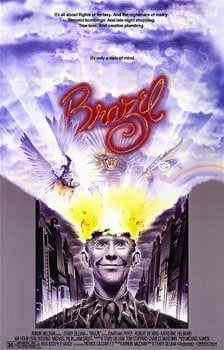

On the other hand, secularism at its worst gets caught up not in the failure of imagination, but in an incapacity to choose the good from among the many possibilities it conceives. War, famine, disease, crime and all other human woes are a result of our failing capacity to bring human imagination into conjunction with the right use of will. As a result, four things tend to emerge. 1. Terror becomes a constant companion as we consider the prospects of the future (think about all those depictions of dystopian futures we see on the big screen).2 2. Imagination more and more takes on the role of fantasy and of selfish satisfaction (fetishism ranging from Ultra-Violence to pornography). 3. Emotions are heightened, as aggression leads to disunity and emotive, irrational arguments become the way that people interact in the public sphere (hello political pundits). 4. Finally, humanity itself is robbed of its relationship with nature and people become parts of a large economic and political machine with no single person at the helm.

The gathering on Cal’s campus was an attempt to offer an egalitarian, practical and conscientious expression of human will for the purpose of justice. It was a response to a world where the soaring language of hope and promises of a new vision have been proven empty. The words and symbols that were once used to describe possible futures often mingle with and morph into the symbols of commercial culture. Ideas about human good and flourishing thus become intricately linked to the financial success of those producing the symbols. There is little done for the sake of the “greater good” without personal gain. The attitude of the occupiers on Cal’s campus was filled with the hope that their movement would not be hijacked by one man’s vision or false promises, but by the shared will of those committed to (more-or-less) just political action.3 Presently, while the movement still exists, its actions are limited by the group’s inability to create a cohesive vision.

***

Now, in the interest of full-disclosure, I have a confession: I was not born a revolutionary. Nor would I claim to be one now. I am still not completely clear about the various ideologies of the “99%” movement and I am not really a fan of the Tea Party. Regarding current events, I am somewhat embarrassed to say that I only keep loose tabs on what is happening in Egypt and Syria, and I am not entirely sure what to make of Edward Snowden. I am a little nervous about the “NSA domestic spying” business, I am apprehensive about the ways that police units are starting to look like paramilitary forces, and I am pretty pissed off by the prospect of large corporations juicing consumers for cash while also destroying the environment.4 Unfortunately, it is difficult for me to find a way of working to fight injustices in the world because there are so few ways of seeing the world that I can agree with. I look to the world around me, for some kind of unifying vision, but I just end up dismayed at the dissent among the so-called “guardians” of our social philosophy.

Still, the more I look, the more I realize that the world is in need of mystics as much as the world is in need of revolutionaries.5 Yes. You heard me right. We need mystics. We need revolutionaries. And, as a Christian, I believe that I am called somehow to embody both. We need people who are willing to commit to a cause and strive for an ideal. Not just any ideal, but ideals like those embodied by the Christ and presented in teachings like the Beatitudes, or named by virtues of Love, Justice, Perseverance, and Courage. We need mystics and revolutionaries because they committed to transformation – of ourselves and the of the world in hopes of seeing a little more clearly the kingdom of God.

Here’s what’s scary: if I really believe this, it is not a matter of doing something on weekends or tramping across a campus to observe people who in the midst of a protest. That is too easy. It requires something more from me – a change of life. And I hate this idea because, the older I get, the less I want to become a revolutionary or a visionary. Those words seem so…I don’t know…charged. I do not want to apply to myself the same language that is often associated with everyone from strange spiritualists to disgruntled and opportunistic agitators. I don’t want to be championing poorly defined beliefs on a college campus, walking with a placard outside the capitol building, or putting up statements on my Facebook page because I am not sure any of it really helps.

Still, transformation comes through action: everyone working together towards something. Even more to the point, redemption and salvation come, not through the exultation of humans choosing whatever they will, but by choosing that which leads towards love of God, faith in Christ and compassion for all. By extension, this requires stewardship: we receive what we are given so that we might share with those in need. To paraphrase St. Ignatius, all of us were created to serve and reverence our Creator, and all things exist to serve this end. This is not a weekend battle, or a one event deal. It is about the ways that we orient our entire lives.

When I think of the various movements of the last couple of years, movements working towards social change and a common good, I have a sense of respect even if I do not agree 100% with what is going on. No, political groups are not faith based communities, and if the vision of the future of society and the revolutionary impulses that guide our actions are not somehow imbued with an explicit awareness of our participation in the Body of Christ, they are falling short. Still, when it comes to movements of protest, at least there is something visible that we can see and participate in that seems to move beyond the limited expression of Catholic social action. Simply put: they are doing something while many Catholics do nothing.

Perhaps this partially explains the current popularity of Pope Francis. For whatever it is that he says, he also appears willing to put his words into action. What makes Francis so stunning is not that he is doing anything that we have not heard about before. It is that he is putting into action, in clear and unambiguous ways, what it means for a person in his position to live the gospel. He has a vision of his life that comes directly from his faith in Christ and he puts it into action. That is a mystic and a revolutionary. In our own particular ways, to give everything we have to the service of Jesus Christ, we are called to the same.

The world is need of people who can dream big, and “dream out loud.” We cry out for a vision that is large enough for our collective consciousness because, let’s be honest, the “American Dream” is running a little thin. The dreams we need must be about the redemption, salvation and transformation of culture. The visions we seek are about Christ. After all, isn’t it the Body of Christ which we profess, and the vision of which we hope will guide us towards an unknown future? Along with this vision, though, there is action. Not the occasional actions of one shot events, and not the easy road of repeating a slogan. It is about a visible movement of collective change. It is about walking the talk.

***

Cover image of Revolution from Vanessa (EY) at Flickr can be found here

— — —

- It is interesting that the same time of rise and fall seems to have happened with the Tea Party movement. ↩

- William Lynch talks about each of these in Christ and Prometheus, 101 – 112. ↩

- Perhaps we fear shared visions because we have seen the horror of what happens when idealistic words get corrupted by the quest for power. And not without reason…it is always possible for the most noble of ideas to be warped into something destructive. I still cannot read Ezra Pound’s “Canto XLV”, sometimes called “with Usura,” without the horrific knowledge that his personal, idealistic vision somehow was intertwined with his support of the ideologies and promises of men like Hitler and Mussolini. Likewise, I cannot look to the problems associated with the disparity of wealth in this world and not hear the words of his commentary, and witness how the practice of usury has the potential to encourage poverty even as it rips the soul from the process of creating goods that will encourage human flourishing. ↩

- Don’t get me started on the XL energy pipeline being built across one of the most important aquifers in North America…which just seems like a recipe for disaster because everyone fears that it is just a matter of time until the pipeline leaks and creates irreparable damage to America’s bread-basket. ↩

- Henri Nouwen’s Wounded Healer and William F. Lynch’s Christ and Prometheus have been on my mind a lot lately. I am obviously not going too far into their works, but you may want to check them out because a lot of what I am writing, I am borrowing from them. At this point, they are classics whose words, now some fifty years after they were written, are proving to be prophetic. What do the talk about? The absence of a unifying vision, the rise of the narcissist, and the diminishment of our connectedness to creation as a result of technology. Their solution? Jesus Christ. While I cannot agree with every word they wrote – after fifty years, perspectives have changed a little. I will say that after reading their words and looking to the world around me, I see the power of faith in Christ in a new way. ↩