Editor’s Note: this is the second part of Jayme Stayer’s essay “Sh*t Christian Poets Say.” If you missed part 1 you can read it here.

***

Last week in the first section of this essay, I sketched a general picture of the problems of religious poetry, including the pitfalls of sentimentality and the difficulties of voicing praise language or exploring ideas that are coarse or unorthodox. To see how contemporary poets negotiate this complex landscape, let’s consider Mary Karr’s book Sinners Welcome (2006).1 Karr’s volume is the best attempt at serious Christian poetry since Mark Jarman’s Questions for Ecclesiastes (1997) and Unholy Sonnets (2000). Like Eliot, Karr loses her footing when she leaves her personal experience behind and tries to “do theology.” A number of her poems are Christological meditations, scattered throughout the volume amid her more confessional poems. In “Descending Theology: The Nativity,” Karr struggles to make such familiar terrain come alive:

[…] his lolling head lurched, and the sloppy mouth

found that first fullness—her milk

spilled along his throat, while his pure being

flooded her.

We are perilously close to bathos here, and once the speaker strides into “pure being,” we know the poet has thrown over the hard work of phrase-making in favor of philosophical clichés. But Karr recovers herself, turning the poem to a more effective ending:

Some animal muzzle

against his swaddling perhaps breathed him warm

till sleep came pouring that first draught

of death, the one he’d wake from

(as we all do) screaming.

In general, this strictly theological stuff is not bad. But it just doesn’t quite work either, though cheers to her for trying.

Karr is the author of the best-selling memoir The Liar’s Club (1995). And so her well-known background of alcoholism, abuse and betrayal already give her sufficient street cred as a religious poet. Before you open the volume, you already know these poems are not going to be ones that Little Flower would have penned. “Delinquent Missive” tells the story of the speaker’s work tutoring at a juvenile detention center. It opens:

Before David Ricardo stabbed his daddy

sixteen times with a fork—Once

for every year of my fuckwad life—he’d long

showed signs of being bent.

The danger of sketching such a character is that the speaker will get stuck in the expected narrative: finding something to love in this troubled child. Fortunately, the speaker offers no such comfort: “If radiance shone from those mudhole eyes, / I missed it.” Writing this poem years after their teacher-student relationship, she can only presume he has by now found his way to the electric chair; she hopes that before this inevitable end “some organism drew your care—orchid / or cockroach even.” The speaker’s human experience finds no spark of God in this sociopath, but her theology is the wiser guide to which she accedes. She walks a tight line by relying on her theology without betraying her experience. She avoids the trap Eliot warns of by not pretending to feel other than the way she feels. When the delinquent waves at her at lunch, she flinches. She does not dissolve in tears thinking that she has touched his heart. She concludes by wishing that

[…] the unbudgeable stone

that plugged the tomb hole

in your chest could roll back, and in your sad

slit eyes could blaze

that star adored by its maker.

This leap to the transcendent at the end of a poem is always a temptation for any poet. (It is Mary Oliver’s most overused trick, and the Poetry Foundation should fine her for every time she reverts to it.) But here, even though the allusion to the resurrection is handled a little clumsily, the hopeful conclusion is warranted.

Karr’s “Waiting for God: Self-Portrait as Skeleton” is another poem that doesn’t shy away from the stench of despair and confusion, this time about her mother’s piteous alcoholism as it played out in her final years. After the mother’s death, the speaker is drowning in her own problems, which involved praying

with my middle finger bone aimed at the light fixture—Come out,

You fuck, I’d say, then wait for God to finish me

where I knelt [.]

There’s that f-word again, even though there are plenty of poems in Karr’s volume that are PG- or G-rated. But I’ve deliberately chosen these last two poems on the assumption that if we’re looking for a barometer of the problem this essay addresses, then cursing in a religious poem is a good indicator of the discursive weather. Looking at how salty language fits into religious poetry illuminates in miniature the larger problem: how do we inject or absorb the varied discourses that surround us into our God-talk? Because of modern censorship issues, cursing in any kind of literature also happens to be a barometer of how secular culture gauges public morality. Allen Ginsburg caught hell from the authorities of his day for using the f-word in Howl. But as a matter of poetic usage, it was not problematic: Howl is not a religious poem. It has a rambling, narrative style, and a hallucinatory (and hallucinogenic) atmosphere. It would have seemed odd if Ginsberg had not used the f-word in such a poem. But in a lyric mode, the word “fuck” has a tendency to take all the air out of a poem, even one that is strictly secular. Whether deployed as a red-blooded curse or a wry exclamation, the f-bomb may have a forceful initial impact in a poem, but on rereadings, it can seem showy: look at me! I can swear!

In Karr’s “Delinquent Missive,” the sociopath’s expression “fuckwad life” is earned, not because it is put in the mouth of someone other than the speaker, but because the poem unsentimentally portrays a troubled teenager. In Karr’s “Waiting for God” though, her “You fuck” throbs like a bruised elbow, unnecessarily calling attention to itself. That both expressions are in italics doesn’t help either. My distaste for the f-word in this poem is not a question of prudishness. (In my personal life, I happen to swear like a sailor.) It’s a question of decorum. The appropriateness of words can only be weighed against an audience’s needs and expectations, and the reasons a speaker has for pushing those boundaries. I might swear with abandon around friends, but I don’t swear from the pulpit when I’m giving a homily. Vulgarity, in other words, resides not in any particular expression, but in a rhetorical situation.2

I would encourage anyone who is angry at God to swear as much as they like in their personal prayer. God’s a Big Guy. He can take some abuse, especially if it’s genuine communication. I’m convinced he’d prefer your skirting blasphemy to pious flattery that hides internal anguish. Karr may have sworn in exactly this manner in her personal prayer. But a poem is a made thing and needn’t strictly record facts as if it were a newspaper article. Poems must find traction in a public language and a public forum. The problem of style is not only communal but historically inherited. It is not a private problem, one that Karr can solve on her own, by making better decisions, for example, or banning the f-word from her poems.

A large part of the problem is the medium of poetry itself: the pressure that the lyric mode exerts on language makes the words vibrate with intensity. The problem of style is solved much more easily in prose. The casual, button-down modes of prose—such as narrative, memoir, or personal essay—are roomier places to switch registers of discourse. Karr’s own prose, as well as Ann Lamott’s, has wedded a refreshingly commonsensical piety to a breezy prose style that would not be out of place in an issue of The New Yorker. Their salty language is of a piece with the humorous, reverent, and affecting stories they tell.

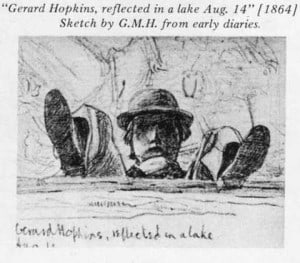

I sometimes joke that the last great religious poet was Gerard Manley Hopkins, who died in 1889. And yet even his sonnets, miraculous as they are, do not add up to a coherent vision or statement on Christian faith. If we had more poets like Karr and Jarman, we would have more religious poems in which nothing human is alien: the full range of human expression, which includes cursing, grumbling, singing, shouting—the varied ways in which we express the operatic extremes of loathing, despair, gratitude, reverence, and ecstasy. But while such a bounty would be welcome, it would not keep us from flinching when we read a poem about the baby Jesus. For that to happen—an atmosphere in which grand Christian epics are hewn from the discursive soil around us—we’d need a paradigm shift, some tremendous cultural change, slouching towards Los Angeles to be born.

— — — — —

- Mary Karr, Sinners Welcome. New York: HarperCollins, 2006 ↩

- If you’re the type of person who does not swear, then my hat is off to you. But here is a very different issue: if you’re the type of person who thinks that no one should ever swear, least of all a poet or a Jesuit, and that “gosh” and “darn” are perfectly adequate expressions of human despair and confusion, then…well…. Then I guess I don’t know what to say, except: gee whiz, how did you make it this far into the essay? ↩