The verdict, given in six unanimous voices, is that George Michael Zimmerman is not guilty.

Seconds later, as Mr. Zimmerman gave a slight smile and shook the hand of his attorney, the massive What-Does-This-Mean? Machine that is “the media” began to crank its mighty gears and issue its own verdicts. Some focus on technical and legal accuracy. Others on how all that accuracy leaves us rather less than satisfied. Still others chug on about the uphill climb faced by the prosecutors.1 They were unable to carry their burden. The jury acquitted.

As I watched the media machine grind on around the verdict, I found my mind going back to one of my earliest memories as a practicing lawyer. It could be any day in any week. I was in court, representing a young African-American man unable to meet his bail amount. The case was called, the bailiffs brought him in. He was wearing the standard uniform of the Dane County Jail and the standard-issue cuffs on his hands and feet. He was led to his seat beside me facing the judge.

And then it struck me. A young black man had been brought in, shackled and wearing clothes he did not choose. Surrounded by white bailiffs, sitting at a table with a young white kid who told him when to talk and what to say. Next to us was a white prosecutor and a white cop. Across the room still more white faces — judge, clerk, court reporter. This was in all respects a routine situation; the day was nondescript and nothing special. I was a part of scenes like this many, many times during those years. But that day it was different. This young man was just one more part of the routine, reduced to a bit player, even though it was all about him. The stark dichotomy between him and us became apparent in a way it never had been before. I reacted viscerally. And the memory has stayed with me.2

***

Trials are weird things. For those of us who work in the court, it’s just another routine, the way anyone’s job becomes routine. A trial can make for a few dramatic scenes and there is always some kind of a hope that a trial can be a source of justice. The theatrics of a trial aren’t just dreamt up, or written in by screenwriters; they are there because of the hope that a trial will be an embodiment of The Law, that justice will be done.

When that fails to happen, then, the problem doesn’t lie just in the trial – in fact it may not lie in the trial at all. The lack of justice may may rest instead with The Law.

The Law is one of the great statements of what we, as a culture, believe. It is aspirational and instructive. Pure in its desire for clarity and prescriptivity. Legal decrees, be they legislative ordinance, executive order, or judicial opinions, are the frame by which our society is governed and give us broad principles of action that instruct us. If not quite reaching the heights of Good and Bad, The Law does set out what our society considers right and wrong. And that – as any Civil Rights participant or beneficiary can attest – is not nothing. The Law is one of our society’s great sites of moral discourse about who we are and who we want to be.

A trial, though, is not that. It just doesn’t work that way. Trials are specific instances of the law in action and are bound intimately to specific facts. No trial occurs in a vacuum; no trial is simply a thought experiment about whether a defendant is a good person or not. Every defendant, every witness, every victim is a real human with good traits and bad. What happens at trial is that laws that already exist are taken and applied. At trial, we see how the principles our society has already adopted actually play out.

***

Which brings us back to the case against Mr. Zimmerman. The difference between trial and law helps us understand the tension we might feel, the frustration and the general sense of unease with the verdict, regardless of whether we think the verdict was good or bad.

And yet, the end of the case is not the end of the matter. Faced with the facts on the ground here, many are frustrated and upset. A young unarmed black man visiting an upscale neighborhood is shot by a volunteer member of the neighborhood watch who followed him on foot and by car. Questions of race, class, and age reverberate. And so we question.

Still, it does little good to impugn the verdict.3 The jury heard the case, was instructed on what the law is, and did its best to apply the law to the facts before it. The extent that we are frustrated with the trial verdict, it is – I believe – the same extent that this verdict reveals the shortcomings in our laws and in ourselves.

Trials like Mr. Zimmerman’s force us to ask questions about the very justice of our justice system. Actually, no. They don’t force us at all; they just perform our abstract laws for us. The outcomes capture our attention and ask us to do something about it if we remain unsatisfied with what we see.

We can mourn for the dead, and we ought to. We can decry wrongs done, and we ought to. We can fight for just laws, and we ought to.

But our hopes for something better cannot, must not hang on the outcome of a particular trial. All that any trial really accomplishes is to put the choices we’ve made on stage for us all to see.

***

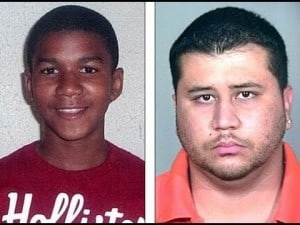

Photo of Trayvon Martin and George Zimmerman courtesy of flickr user zennie62

— — // — —

- N.B. none of these commentators are anything close to incorrect. And as for the challenge faced by the prosecutors, it is true that were forced to prove – beyond a reasonable doubt – not only that Mr. Zimmerman killed Trayvon Martin (something that was never really in doubt during the trial) but also that he was not acting in self-defense. And Florida law had a broad self-defense justification. ↩

- Even beyond the racial component, there were serious questions of class and education as well. A criminal defense lawyer I know once remarked that the criminal justice system is often a matter of the legal imposition of middle-class bourgeois norms upon a poverty-stricken caste for whom such norms are alien. ↩

- To be clear, even if the verdict was wrong across the board, it cannot be legally challenged as the Fifth Amendment prohibits re-trying a defendant who has been acquitted. There are possibilities for civil charges or perhaps even federal charges, but this particular verdict is final. ↩