Big Night Last Night

This election year is all about the economy, or so we are being told. We sure heard quite a bit about it in last night’s first presidential debate.

Facts first: over the past year or so, most of the US unemployment numbers have been disappointing – not that the blame for this falls at the feet of the current administration alone. No, I am of a mind with West Wing President Jed Bartlet (who had himself a fictional doctorate in Economics to go along with his fictional professorship at Dartmouth), who said: “I don’t think that the president has much direct influence on the state of the economy.”

Why do I think that, you ask? It’s straight supply and demand.1

I know. It ought to be more complicated, right? But that’s really what unemployment is about: too high a supply of labor, too low a demand for that labor; too many people available to work, too few jobs available to be grabbed up.

In this dime store definition we sort of get, really, the whole problem of unemployment. The economic principles behind it are kind of … easy, actually.

Like most easy things, the problems come later. Like so many other things, it’s when we have to figure out how those principles work in the quote-unquote real world that economics gets murky. For unemployment this means that it gets complicated as soon as we realize that we actually have to figure out what those simple words “supply” and “demand” mean in terms of real people and real businesses. And, in all fairness to Mitt Romney and Barack Obama and even Jed Bartlet, that’s a lot harder to figure out.

***

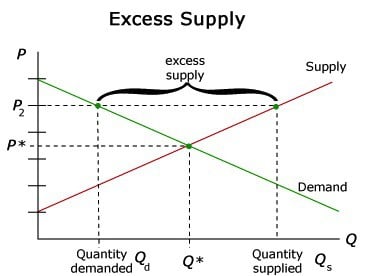

Starting small is usually a successful tack when taking on difficult problems, which is why I want to start by talking about minimum wage.2 Some people (smart people) say that this, minimum wage, is what the unemployment problem is really about. You can see their argument if you check out the chart below – the demand curve (the downward sloping, green line) and the supply curve (the upward sloping, red line) intersect right at the heart of the graph. And if the minimum wage were set at the place where those two curves meet (at P*), all would be well. The story then goes that because the minimum wage has been legally set to a minimum that is higher than the intersection point (check P2 now), we have effectively legislated, with good intention, a situation of excess supply. The difference between P* and P2? That’s unemployment.

TJP, Your Online Home for Fancy Charts

So… maybe we could just do away with minimum wage for awhile?

It seems to make sense, but now there are other considerations. For example: do we really want to go back to 19th century-type labor conditions just because it’s better for employment numbers? It might mean that businesses would hire more people, but there are enough people struggling to make ends meet while making a supposedly inflated minimum wage that this proposal begins to sound pretty weak pretty quick. And I think both real parties and Jeb Bartlet’s fake party would agree.

But just because getting rid of the minimum wage isn’t a great solution doesn’t mean that the cost of labor doesn’t matter either. Full disclosure: I grew up in France, and in France hiring someone full time is very costly.3 Like most European countries with a large welfare system, unemployment is typically higher in France than it is in the US or Great Britain. Forget having a clerk bagging your groceries at your local Parisian supermarket, that’s too costly. And you never see as many doormen in Paris as you do in Manhattan. In very costly labor economies, the jobs that are not producing stuff you can sell (the doorman) or that are not absolutely necessary to a business (the bag clerk as opposed to the cashier) are very rare. Euro-details aside, the point is this: how much it actually costs a business to have an employee has got to affect a country’s level of unemployment.

So minimum wage is part of the unemployment problem, but it’s not the whole shebang. You’ll notice that the jobs that are missing in my all-too-brief discussion of European economics are low paying, service sector jobs. And these are not the jobs Gov. Romney or Pres. Obama were talking about last night. Last night, coming from televisions across the U.S. we heard two words again and again: middle class. We heard the candidates saying that most of the people looking for work in the U.S. come from the middle class.

And it’s true.4 The crushing of the middle class5 is the biggest economic problem of the past few years. Middle class folks are losing their jobs in waves, and a lot of recent college grads are stuck in neutral looking for a first job. The issue, then, is not really one of minimum wage but of economic policy; specifically having the authority to put into place economic policies that help create middle class jobs.

***

What most economists think today is that unemployment – and many other economics quandaries – can’t be solved by perfect economics alone. Good policy is a sine qua non for a good economy. It’s policy that will get businesses rolling again and policy that’s the central issue. All of this is sometimes admitted by economists (and fake-presidents-who-used-to-teach-economics) with something like a sigh of relief – because it means that all of this mess is really in the hands of Congress, CEOs, and consumers.

So, if unemployment is really a policy problem, the question of how to remove the noose from the neck of the middle class becomes: which policies can we put in place that will give a boost to the U.S. economy? But oddly, or maybe not, it’s another question that starts simple before it gets complex.

Because what everybody says in answer to the question “what will get businesses hiring again?” is: incentives. “Want good business?”, they say, “Give them good incentives.” And that’s what everyone (yes, really everyone) running for the House, the Senate, or C-E-O of the U-S-A is arguing about. What are good incentives? Which will work best?

These are the questions that keep key members of the Obama and Romney economy-teams awake at night. Incentive questions.

And, as with our party system, there are two main schools they look to for answers.

1) Let’s take the supply siders first. Supply siders tend to think that we need to focus on incentives for the supply side of the economic markets. They want to incentivise organizations that provide goods and services (that’s politics code for “businesses”) to hire more. This might mean giving businesses or business owners tax breaks, or making it easier and cheaper to hire and fire personnel. It might mean less governmental regulation. It’s the supply siders who want to give incentives, financial and otherwise, to CEOs or talented business managers, and it’s the supply siders who argue that businesses ought to be required to have fewer mandatory benefits (hence the debate on mandatory health care).

Demand Policy in Action

2) On the other hand we have the demand policy makers. Instead of focusing on business, demand policy makers ask: how can we get people to buy more stuff? Can we get the auto market back on track by incentivizing people to buy more cars? Maybe we need to offer a subsidy so that people will get rid of their old cars and buy new ones… or maybe we need to lower sales taxes across the board… or offer tax credits? Demand policy makers also tend to focus on providing increased job security and social safety nets, not for moral reasons, but because safety and security mean a more stable income and thus a more smooth pattern of consumption. Other than influencing consumers, the other tactic that demand policy makers have in their toolkit is to have the government do the work itself. Hence the renovation of highways and the building of bridges and etc. The old New Deal is a tad passé, but it’s still in the air.

You could say, generally, that Republicans are on the supply side and Democrats on the demand side. But when it comes to policy the lines blur. George W. Bush offered both the famous “Bush cuts” for higher earners in America and protectionist policies to the steel industry. Bill Clinton repealed the Glass-Steagall Act making it easier for banks to do business on both the commercial and investment sides (and is sometimes thereby credited with playing a key part of the Wall Street housing market collapse), but he also opened his first term by discussing on a health care system for all Americans, which runs completely against supply side views.

The reality is that no major politician stands squarely on one side of the policy fence, and this goes even for nationally televised debates like the one we saw last night.

And that’s the frustration that haunts economists like me. We are important these days – people ask for our input all the time. And our models are beautifully and carefully put together. But in the end all our advice and all our diagrams seem to be little more than framed pictures hanging on the wall of the Oval Office. Instead it’s about the politics, and that means having to deal with a lot more than fifty shades of gray.

***

So, as we watch the rest of the presidential debates unfold, and as we continue on past Super Tuesday and Inauguration Day and all of it, what should we remember?

We need to remember that we need to talk. Yes, this phrase comes around even for us celibate Jesuits. And no, no one I know likes to hear those words “we need to talk” – because all-too-often it means that something is wrong. Did I mess up? What are we not doing right? Can I handle this here and now?

Personally? I think I dread those four words don’t want to know what am I going to have to compromise on today.

And the same goes for politics. We can’t have conversation about policy, let alone economic policy, if we are inflexible. The political gridlock evident in members on both sides of the aisle is costly. It costs us in terms of the interest rate we pay on our national debt.6 It is also costly in terms of time (how many weeks and months of policy implementation have been wasted in political standoffs over the past couple of years?). And wasting time means wasting opportunities for job creation; it means that millions of people remain out of work; it means keeping the economy in neutral rather than kicking it into drive.

Everyone around the policy-making table should be grown-up enough to accept the four most uncomfortable words in politics (and in Jesuit communities). But we do need to talk, and we need to know how to compromise too. But they’re all adults. And the time to have the hard conversations is now.

For me the point of all this is a simple one in that it rests on one premise: politics is lot like football.

It’s a contact sport. I think that if we understand what the real sacrifices are in the unemployment issue we’ll be able to read the candidates better. And we need to understand the plays that Gov. Romney and Pres. Obama have drawn up. We need to know their offense and their defense, we need to be able to read their formations and routes, their coverages, audibles and all the rest.

And it’s like football in that it is intimately bound up in deception. We all know that no candidate will make good on all their promises. We all know they will compromise. So as we watch the debates and read the papers, I suggest a thought experiment.

See your candidate sitting down with other adults at the negotiation table to talk. Then ask a few questions: Will they show up knowing they need to talk? Do they understand the issues and think well on their feet? Can they compromise? Do they know how far afield their compromises can take them?

***

I have a friend who is a talented economist. He has an MBA and a PhD in economics. He’s a CPA and has taught in law schools. He’s worked for the executive branch in Washington. All this to say: when he talks about this stuff I listen. And what he’s said to me is this: the economics side is easy to figure out; it’s the political aspect of things that’s difficult. Really difficult.

So, as you look at your ballot think about whether you can see your candidate at that table of compromise. Imagine the look in his face as he hears those four not-so-magic words: we need to talk.

— — — — —

- You might have just run by that supply and demand link thinking that it was a link to some very technical, super intellectual, academic-y paper about economics, and if you did, hey I totally understand. But it was actually a link to a super great live version of The Hives singing their great song “Supply and Demand”. I only mention it in case you, you know, have good taste and like kicking punk rock tracks backed by fairly accurate economic principles. ↩

- Badum-bum! ↩

- Typically, giving someone a solid, 50,000 euro annual salary winds up costing a business about 100,000 euros; that’s because mandatory benefits and business labor taxes are very high in France. Even more, the newly hired person still has to pay income taxes on his/her 50,000 euros. ↩

- Heck, we are living in times when even law firms are struggling – surely that’s one of the signs of the apocalypse. ↩

- I’m trying to avoid using the phrase “squeezed middle” here even though it got the “fully acceptable” stamp by the OED about a year ago. ↩

- That’s the issue about rating agencies “downgrading” the US: these agencies are saying that buying US debt is more risky, so we have to give people more money as an incentive to keep buying our debt ↩