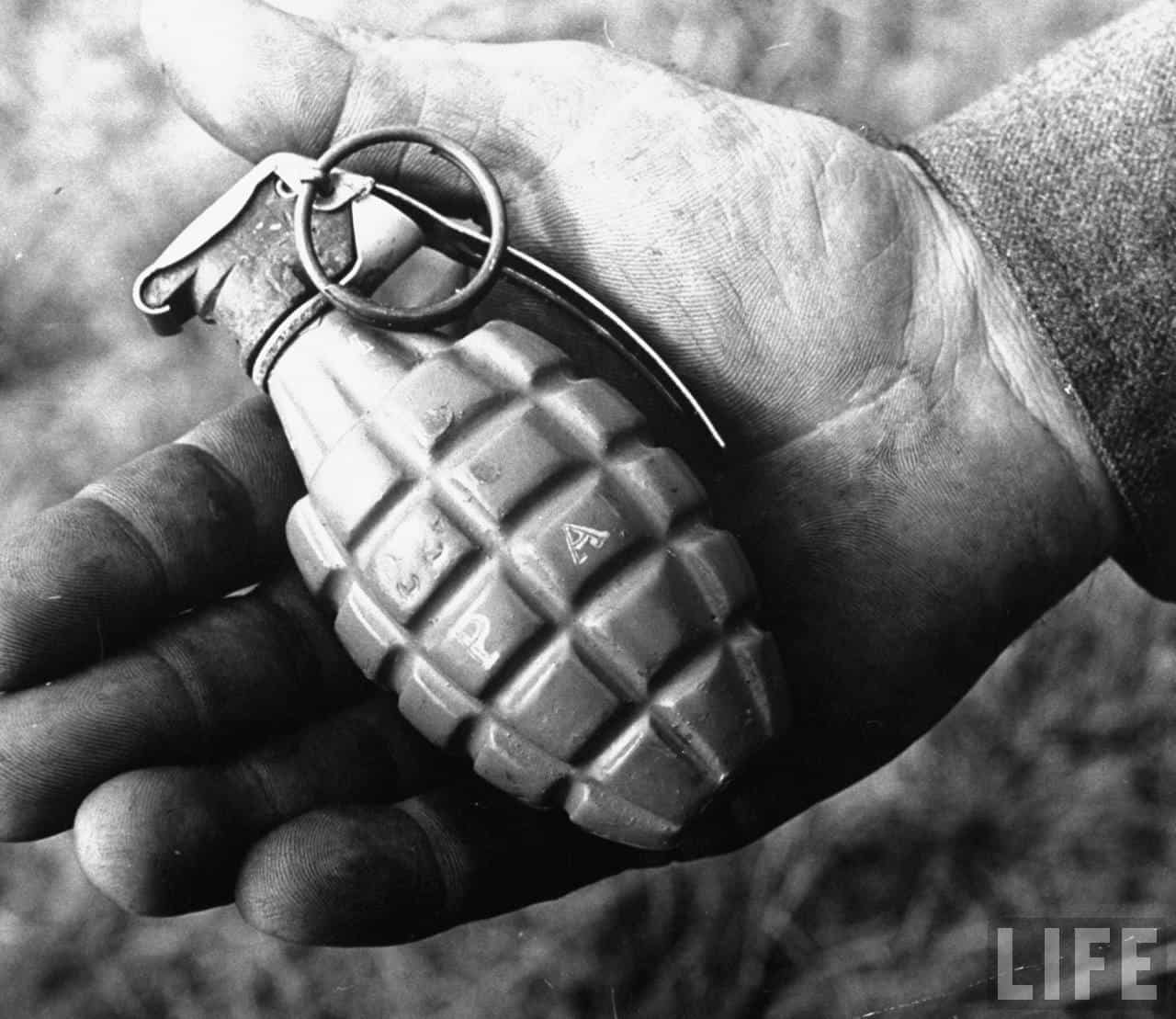

Terri Schiavo.

Cardinal Law.

Fr. Cutie.

Margaret McBride.

Obamacare.

The LCWR.

Tossed into a room, each of these symbolic hand-grenades can be counted on to create explosively heated discussions. Depending upon which side of these debates we fall, on whether we support or oppose the theses these symbolic grenades pose, a Catholic is identified. Of late it seems that these different sides have started to crystallize; the patterns that identify them seem increasingly apparent. Sadly, these spiritual and doctrinal conflicts seem to have become war-zones of politicized rhetoric and impassioned pleas – all of which does little to promote mutual understanding and goodwill.

Our Catholic Church has now lived with the Second Vatican Council for fifty years. As they have passed, two fairly distinct groups of Catholics have emerged out of Vatican II. Both are convinced of the importance of conscience and the need for a strong Catholic identity. Both groups are convinced that they are living in a direct response to the call of Christ. Both acknowledge that they are sinners called by God to minister to the needs of God’s people. Both groups rely on tradition, and see the need for a more coherent articulation of (and adherence to) the faith they have received.

The longer we listen to each group, however, the more we realize that the polemical atmosphere in which both are speaking is giving birth to a spirit of ill-will and that a tense anxiety is arising where a spirit of charity ought to be. Strangely (and thankfully?), our Church is no stranger to the struggle to articulate a new iteration of the ancient revelation of Jesus Christ. If it is examples we need, we need only look to our Ecumenical councils.

Before and after each of these twenty-one councils we can see different spirits pushing and pulling at the people who make up the Church. What is more, at the points of greatest tension, people on both sides of the conflicts always think they are right. And after it is all settled and done, some wise fools always end up standing on top of the dogmatic pillar put in place by their forebears and saying: “Obviously it would end this way. Orthodoxy will always prevail. It was clear from the start that we would arrive at this right conclusion.”

To these I will say this: if it looks clear to you now, it is only because people struggled, argued, and prayed, because our ancestors in the faith suffered and worked to give birth to the orthodoxy we now claim. We should not miss the reality that, from Christ to Holy Cross, there has never been anything easy or clear about expressing a universal faith. Looking to the past we see that the deeper the issues ran, the more tension was stirred and the more entrenched people then became in their positions. It is not just today that this is happening. No, it is because this has happened in the past that we are the Church we are.

***

People used to kill each other over stuff like this. We ought to remember that.

Holy Lego Grenade

And while Vatican II hasn’t been the cause of any bloodshed, it does seem increasingly difficult to say much of anything without being called a liberal or a conservative these days. I want to take note of those two words especially, because the conflicts within our Church seem to circle increasingly often around a politicized conservative/liberal divide.1

How about this, though: what if we talked about these conflictual issues, these symbolic grenades, not in political language, but as expressions of identity? What if we paid more attention to how the labels we apply and the sides we choose identify us as believers? Instead of settling for politicized labels, what if we asked how the sides we take name us, become part of how we identify ourselves? It seems to me that fleshing out of questions like these will give us a deeper grasp of the conflicts facing us today.

Let’s take, as an example, the liturgy. As most of us know, recently the English translation of the mass was changed so that the language would reflect a deeper similarity to the Latin. It is generally acknowledged, by all parties, that the older translation of the mass needed to be updated. Still, in the way that this new translation came about the new mass became yet another symbol of the struggle between right and left. For some, the changes to the mass are welcomed, and welcomed because they show that the governing body of the Church is still governing. Such changes are also welcomed because they mean that Catholics are being asked to participate in a mass that more closely resembles its Roman lineage. And, for this group, the changes to the mass were welcomed as a return to a more universal practice of faith.

For others, the same event gave only further evidence of a mis-prioritized, overly restrictive Magisterium. The changes to the mass meant not universalization, but that Church leadership was more concerned in rearranging the furniture on the Titanic than in reading the signs of the times. Those in this group asked: how is it possible that anyone could think that rewriting the liturgy is as important as addressing issues of poverty, education, and our failure to care for the powerless?

In both cases, read through the lens of identity rather than just politics, we see people taking sides, people staking their claim about who they are through their respective responses.

Those who think that liturgical rubrics ought to be precisely followed and who desire more Gregorian chant tend not to support sweeping statements calling for a “preferential option for the poor.” Those who are prioritize social justice tend to have a looser sense of liturgical uniformity and prize a feeling of community over a type of ritual rigidity.2 It is as though each claims to be practicing a more authentic form of the faith, and therefore to be more Catholic than the other. Of course both groups could, in some ways, be described as “cafeteria” Catholics (a phrase I use here as a non-pejorative term, please see the footnote citations) – working hard to decide which beliefs they will adhere to while turning away from those which do not fit into their sense of what it is to be Catholic.3 Each of these stances reveals a conflict over identity; each of these reveals the way conscience is invoked; each reveals reflexivity in action.

All of this leads to two basic observations. First, we need to recognize how important Catholic identity and the primacy of conscience are while also remembering the normative role of Catholic dogma. This is not impossible. (Yes, I just said dogma. And, yes, I also have to say that dogma is the one of the most important reasons that our faith exists. Dogma is not a bad thing.) Second, as Catholics we need to acknowledge the vast plurality that hides beneath the label “American Catholicism.” This will mean confronting the fact that there are different ways of particularizing our universal faith within an individual life. And, no, neither is this impossible.

In fact, I think that many Catholics are beginning to realize that we have survived as a Church not in spite of, but because of the polarities that have existed within our Church body. The struggle we are facing is our attempt – ours, in our time – to bring to birth an expression of Catholicity that addresses the strengths and inadequacies of our different perspectives.

We, in our time, are actually witnessing people – our own contemporaries; our selves – sift through their understanding of faith and come to terms with it in a public way. Surely this is as amazing as it is potentially troubling.

***

If we think back to our Ecumenical councils, to Nicaea and Chalcedon and Ephesus and the Lateran Councils and Trent, we can see that conflict is not a new thing for us as Catholics. Each Church council has had to deal with serious conflicts over our beliefs, conflicts that challenged them to reframe what it meant to be Christian. We have even seen the Church make massive ideological shifts on particular expressions of belief.4 We have faced conflict and trusted that the Holy Spirit would be present as we worked through problems in our utterly human ways. Facing conflict, trusting God. That is how the Church survived.

Our divisions are deep, it’s true. We are divided over the liturgy and over the preferential option. We argue over politics, sexual orientation, gender roles, and procreation. We struggle about the meaning of the inadequate number of priests, ask questions about what it means to be orthodox and obedient, and feel the hard bite of distrust and betrayal. And none of this reveals a Church suffering from lack of care. We are facing the conflict, we are wrestling with how to live as Catholics in our day and age.

The earth feels as though it is shaking, and we worry that we will be swallowed up, but the struggle we are enduring right now is not as great as those we endured before and after Nicaea in 325, or Chalcedon 451.

And this because, just like at Nicaea and Chalcedon, these debates are not being driven by a group of religious, by a bench of bishops, or by the Pope. Today’s debates, like yesterdays, are being driven by the needs of the people of God.

And in the future, when this debate has ended and the dust has cleared, the Magisterium will name the final boundaries at which we’ve arrived. And, like today, there will be people both outside and inside that line. Just like at Trent, or when our first Pope decided that it was okay to eat unclean food, we are in the midst of a radical struggle over where those lines are going to be drawn.

It is a painful thing to watch happen. There is no easy fix. People will be hurt.

***

The heart of the matter is this, and this is why I have written these words: I am asking us to stay in the conversation.

Every time I turn around I hear of Catholics who have decided to leave the Church because they do not recognize the Christ being professed by other members of the assembly. If I turn again, I am confronted by smug articulations that define with certainty a truth of the faith while neatly sidestepping objections raised by other members of our assembly. Just like our sense that there are liberal and conservative factions at work, we have fallen prey to the idea that there are only two options: to speak so loudly that we drown out the other voices, or reject the conversation altogether. This is where we fail.

Remaining, for us, is neither a matter of obligation nor of choice. It is something different. It is a matter of our willingness to acknowledge that we are in a covenantal relationship both with God and with one another. We do not honor that covenant by belligerence or by ignorance.

I ask us, from a place of prayer and informed conscience, from a sense of self that is united with the entire Body of Christ, to remain. I ask us to offer our lives to living the faith we have received.

— — — — —

- A divide, stolen right out of the political discourse as it is, which seems to me to be one more example of how religion is increasingly being defined by politics rather than vice versa. ↩

- Don’t take my word for it – if you want the hard data, check out Jerome Baggett’s recent sociological study of Catholic Parishes Sense of the Faithful. Page 234 is particularly relevant. ↩

- Baggett speaks directly to this on page 73, and again on pages 215-16. ↩

- E.g., the council of Jerusalem’s decision regarding Gentiles and unclean meat, or the council of Chalcedon’s rather shocking conclusion that Jesus Christ is rightly understood as both fully human AND fully divine… a statement that is both logically impossible and utterly vital in creating the kind of mind that can be opened to the infinitude of expressions of our Transcendent and Immanent God ↩