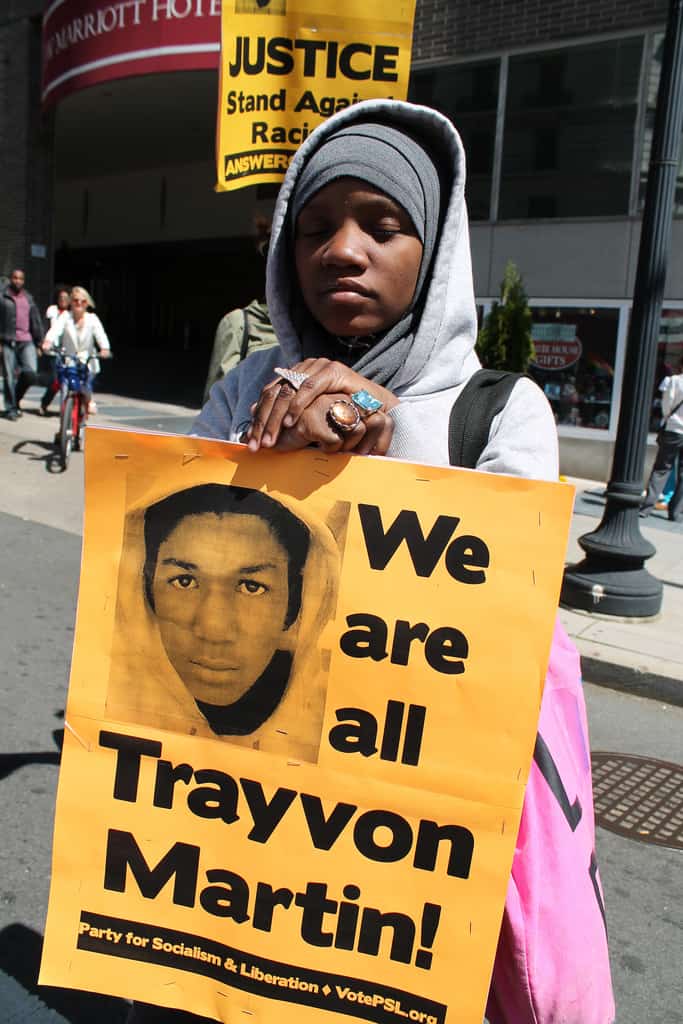

I am Trayvon Martin. When I heard about the killing of this young man, I felt crushed. I felt enraged. I thought about those friends, fellow parishioners, former students, who could have been victims of such fatal racial profiling. I read with sympathy about the Miami Heat’s visual statement of solidarity. I silently affirmed that I too was one with Trayvon Martin.

Yet I am not Trayvon Martin, and it is because of this difference that Trayvon is a national cause célèbre and I a sympathetic witness. You see, I am white.

If I had been walking through that same Florida suburb wearing that same gray hoodie, all appearances indicate that I would still be alive, likely never even raising the antennae of para-lawman George Zimmerman. But Trayvon, a young black man wearing a hoodie, was killed, and this fact has ignited yet another national conversation about stereotyping, racially motivated policing, and double standards.1

It’s something of a truism that any progress toward racial harmony must build upon commitments of solidarity. But I think it is more important, more productive right now at least, to reflect not on sameness, but on the reality of difference. I fear that moving too quickly to a denunciation of the murder, too quickly to an affirmation of the aggrieved family, would be, in the words of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, cheap grace. “Cheap grace,” he writes, “is the preaching of forgiveness without requiring repentance, baptism without church discipline. Communion without confession. Cheap grace is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ.”

Fortunately, standing publically against racism has become something like cheap grace in our society. No one says that they support the killing of innocent teens carrying Skittles. And thank God for that. But maybe this very ease can lull us to sleep, and keep us from asking: how do I participate in practices that led to that killing? Or: Do I benefit from them?

I submit that such questions are piercingly essential. I submit that this style of tough reflection is the kind of Bonhoeffer-inspired discipline that may lead us from cheap grace to real; that may bring us all to repentance and to a more authentic discipleship.

***

Myself? I have become increasingly mindful of how other people have different attitudes towards the police than me. I grew up secure in the knowledge that the police were there to protect me. Sure, movie cops could be corrupt or state patrolmen might write me a ticket for speeding, but I was taught – by my parents, by my school, by the Boy Scouts, by everyone and everything, really – that the police were there for me.

It shook me when I started to realize that wasn’t true for everyone. My first year at college at Saint Louis University, I remember a particular high profile police shooting where two unarmed suspects were killed by a hail of bullets from police. It was not a simple case – the suspects were trying to escape in a car and that certainly could have been interpreted as a threat – but the sheer excess, the use of over twenty shots to kill both the driver and his passenger left… a sour taste in my mouth.

And time after time my ministry as a Jesuit has put me in contact with people who have suspicions of the police, have had bad experiences with the police, or simply belonged to a group which has suffered from racial profiling. These were people I had not mixed with growing up: the homeless living along Hennepin Avenue in Minneapolis, the Mexican Americans who were my students in Denver, the black Catholics who were my fellow parishioners on St. Louis’ struggling North Side.

After the death of Trayvon, it is the differences between such groups that have gained national prominence. I remembered a personal testimonial about racial profiling I had read just before the Martin case occurred. And since the killing, other commentators have acknowledged the anguish of African American parents who recognize that their children’s skin color puts them at risk. Naturally, they do everything they can to warn their children, to protect them, to communicate to them a wariness about potentially abusive authorities in the hopes that such a wariness could end up saving them grief, or their life.

It is the regularity with which these experiences of prejudice and caution are described that unsettles me. My childhood, innocent of such suspicions, contrasts so strongly with what person after person named as just another fact of life for black Americans. One writer described having to let his 12-year-old son in on the “black male code.” It is a code that advises, “Never argue with police, but protect your dignity and take pride in humility. When confronted by someone with a badge or a gun, do not flee, fight, or put your hands anywhere other than up.” Another called the process by which these warnings are passed down from generation to generation “The Talk.”2 If good can be found somewhere in the killing of Trayvon, surely a part of it is the willingness of black parents to bring to light the ways they cope with generations of fear, a fear caused by our country’s history of racially motivated policing.

Growing up a white suburbanite, I never received that talk. There was no need. The worst trouble with the law I anticipated was talking my way out of a speeding ticket. Strangely enough, though, I did end up developing a code of my own for dealing with law enforcement.

***

You see, as I went away to college, I found that I did my best reflection/prayer/conversation on long walks during the late hours of the night. A friend of mine and I regularized this experience, calling it a “jaunt.” Jaunts gave us the opportunity to connect on a deeper level, a chance to talk about deeper desires and fears that could not be brought out in the mundane daylight that covered our ordinary interactions.

They also gave us an opportunity for fun, the kind of fun that entailed exploring unexpected or “prohibited” locations. Jaunts have taken me to the employee corridors of ritzy hotels, into the underground access tunnels of engineering labs, and through closed campus buildings.

It was this last that led to my first encounter with an officer of the peace and sparked the development of my own code. I was with a friend of mine, a freshman classmate, when it happened. We had, quite innocently,3 overstayed our welcome in one of the study rooms in the university library. By the time we figured out that the lights in the stacks outside our study room had not been accidentally turned off, it was 15 minutes past closing time. Given the place to ourselves, we found that we could not pass up the opportunity to explore the empty library, especially not since we knew that the library connected to the supposedly haunted Dubourg Hall next door. (I strongly suspect much of our decision making at this time was influenced by the movie Ghostbusters.)

We did not get far before a flashing light convinced us that something was amiss. We turned around and headed out of the library, confirming as we left that the alarm panel had noted our wandering. We got as far as 20 feet away from the entrance before a campus police officer4 came strolling up. It was decision time. I could deny all involvement, as implausible as that might be a mere 20 feet from the library doors. And lying would likely only make the trouble worse. Yet I was not sure I wanted to tell the full story about attempting to traverse from building to building after hours, either.

“Did you two come from the library?” the officer asked.

“Yes,” I tersely replied. “We were inside when it closed, and I think we set off an alarm.”

And there it was, my code: say no more than you must.

The officer took our student ID’s and called our names into the public safety office, but five minutes later we had been released without so much as a stern word, probably deemed wayward but harmless youth with clean records. And I recognized that the truth – but absolutely no more of the truth than was specifically requested – was the best way for me to deal with these situations.

***

I still jaunt. And while my jaunts have mellowed since my youth, I still have periodic need to draw upon these guidelines when local law enforcement takes an interest in my late night wanderings. To be clear, though, I do not tell this story to show that my own code is similar to the one passed down among black families. In fact, I draw precisely the opposite conclusion.

I have never suffered from these encounters. Sure, I have to submit to the occasional questioning. Perhaps even to a terse order to “scram.” Once they asked to go through my bag. I obliged. But never have I felt disrespected. Never picked on or isolated, never frisked or even touched. Never at risk of something going wrong. Say, something going so wrong that it may cost me my life.

That is not similar to what I’ve read and heard lately about the black male experience. That is different. I doubt I could continue to indulge my love of the night air in quite the same way if I had different skin color. And that gives me pause as I go out for a jaunt these days… How much am I trading in on my skin color to do this? Who does not get the benefit of the doubt that I get?

And so I am brought to the strange conclusion that declaring “I am Trayvon Martin” is not the best way to express my solidarity with him or even with my friends and fellow parishioners who have suffered from racial profiling. Instead, I think my task is to publically announce that I am not Trayvon Martin, and to denounce the differences between his circumstance and my own as being against God’s plans. I hope that this, in some way, contributes to the healing of American society.

White Americans must recognize how the legitimate respect we take for granted does not trickle down to all groups equally. On the basis of this recognition, the fear and laziness that motivates racial stereotyping can be challenged, even eventually ended.

So, if I can talk straight to you, reader, at this last moment, I’d like to ask you to please take the time to read one of the above commentaries about the black male code. Or to think about the connection between Trayvon’s death and our culture of fear. Maybe examine how our demands for safety may actually cost others the chance for safety. I ask because I hope that such reflections will help us refuse to settle for the cheap grace of saying “I am against racism,” and instead begin in each of us something of the rigorous self-examination and repentance that characterizes true discipleship.

— — — — —

- Of course, many of the most insightful commentaries on Trayvon Martin’s death place the racial issues at stake in a larger, more complicated context. At the end of this piece, I suggest some of my favorite such articles. But I believe that there is also value in honing in on one particular issue, to understand it better, even if reality rarely operates according to such clear categories. ↩

- Although, thankfully, they are not passed on without alteration. Many of these same commentators report that the exhortation to “protect your dignity” had not been possible before the civil rights movement because a black person claiming dignity would have led to immediate counterattack. ↩

- Only the dorkiest of college nubes can claim to be surprised that the library closes early on Friday nights. We were. ↩

- This being my first run-in with late night law-enforcement, I consider myself lucky that we did not encounter a bona-fide city cop – I might have wet myself. ↩