You may have heard the story about the rabbi and his young son. The boy liked to wander in the woods every day when he got home from school. At first, the rabbi let him wander, but over time he grew concerned. The woods were dangerous and the father did not know what lurked there – think Peter and the Wolf. One day the rabbi sat his son down and asked, “You know, I’ve noticed that every afternoon you walk in the woods. Tell me, son – why do you go there?” The boy replied, “I go there to find God.” “That is a very good thing,” the father replied, smiling. “I’m glad you’re searching for God… but, my dear son, don’t you know that God is the same everywhere?” “Yes,” the boy answered, “…but I’m not.”

I thought of this a few weeks ago, as I sat reading Eric Weiner’s piece in a Sunday New York Times, Where Heaven and Earth Come Closer. Weiner explains that there are certain “thin places” (as the Irish would call them) on earth that open us to the transcendent. Heaven feels just a little closer, and God just a little nearer, than in the usual places we inhabit. Weiner asks, “the question, of course, is which places? And how do we get there? You don’t plan a trip to a thin place; you stumble upon one.”

Much of his article is Weiner listing (bragging about?) some of the thin gems he’s seen on his travels. Much of my reading consisted in envying his globe-trotting. From New York to New Delhi, and from Konya to Katmandu, Weiner has seemingly stumbled upon more tucked-away thin places at every turn, and each of them helped him feel more connected with the Transcendent, more in tune with himself. Most of us don’t have the resources or time to travel the world or to indulge our taste for Weiner’s Eat-Pray-Love-style “quest for ourselves.” But that doesn’t keep us from encountering God in our own thin places, places that don’t require a life of leisure and $5k to helicopter up to the base camp of Mt. Everest.

***

I’ve had the good fortune of stumbling on a few thin places; I suspect most of us have. These are the places where time no longer matters, or rather as Weiner quite poetically puts it, “our relationship with time is altered, softened.”

I discovered one such place recently. It is St. John’s Abbey in Collegeville, Minnesota. I visited there at the recommendation of a brother Jesuit a few weekends ago, and found myself instantly relaxing from the stress of the week gone by. The Benedictines’ guest rooms are bright and clean; spartan but comfortable. Time slowed and the sun shone bright over Lake Sagatagan as the campus crawled out from the sleepy blanket of winter. Campus sidewalks were filled only with rivulets of melting snow, while students were off enjoying warmer (warmer, with this Midwest heat wave? I asked myself) spring break climes. I passed the time jogging, reading and walking (with hands appropriately clasped behind the back, of course). I prayed on benches in the sun and let the unseasonably warm breeze fill my lungs. The first housefly of 2012 landed on my arm.

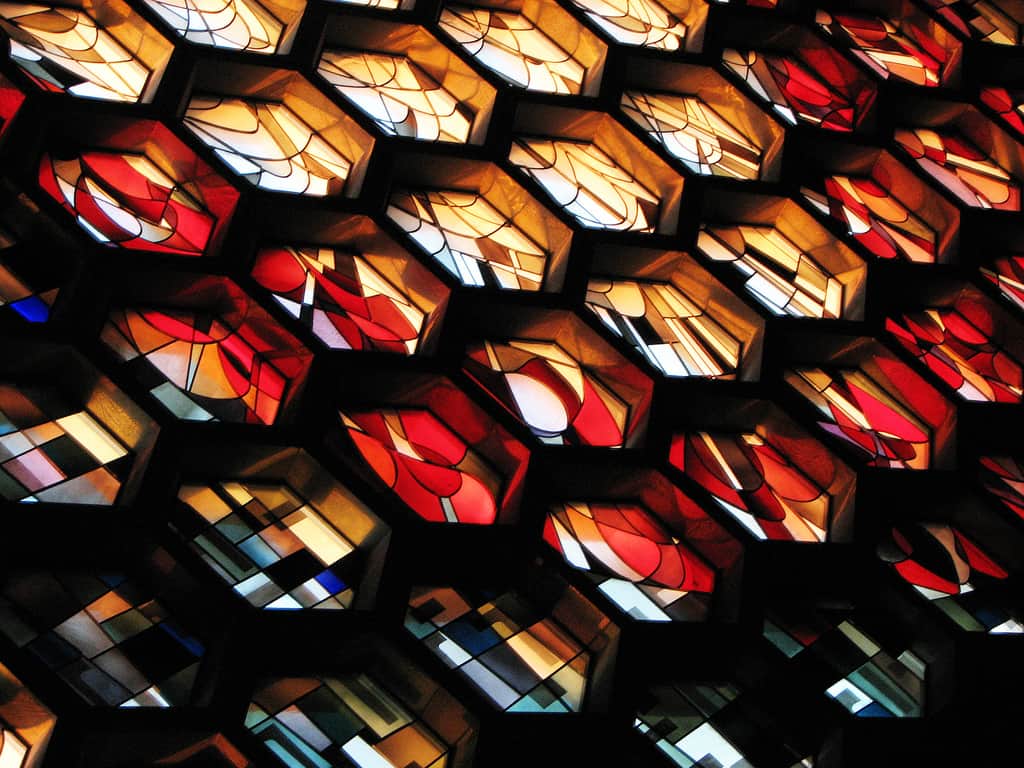

I joined the long line of black robed monks chanting morning and evening prayer in Marcel Breuer’s cavernous bauhaus Abbey Church, which has been designed to look like a giant concrete beehive. I was struck by the quiet, swift way the monks bowed first to the altar and then to one another as they took their seats in their choirstalls. Because this, of course, is a Benedictine university, several times a day these men gather to pray the psalms, singing them in spartan tones that date back 1,500 years. During one such prayer a monk lit a large bowl of incense, which quietly rose and enveloped the crucifix suspended over the altar. “Like burning incense, O Lord, let my prayers rise to You,” I thought.

Time and worries softened, peace came over me; and I wanted to be nowhere else at the moment. Frankly, I’ve been soaking in the memory of those moments for weeks. This is an experience of what we Jesuits call consolation, and I’m guessing that consolation is what Weiner is really trying to name when he describes the lovely experience of stumbling on, and savoring, a thin place.

***

Another phrase used often in Jesuit parlance is the commission to “find God in all things.” This is helpful if we understand it as recalling that God is laboring at every moment – even in challenges and distractions, even when we turn away from God. Ignatius had a keen sense of God’s laboring love. But as far as my ability to find God in all things? Well, like the rabbi’s son wandering the woods, I tend to find God in certain places and spaces not because of some lack in God, but because I am not the same everywhere. Weiner again:

[U]ltimately, an inherent contradiction trips up any spiritual walkabout: The divine supposedly transcends time and space, yet we seek it in very specific places and at very specific times. If God (however defined) is everywhere and “everywhen,” as the Australian aboriginals put it so wonderfully, then why are some places thin and others not? Why isn’t the whole world thin?

Maybe it is but we’re too thick to recognize it. Maybe thin places offer glimpses not of heaven but of earth as it really is, unencumbered. Unmasked.

Like the rabbi’s son, I’m usually too thick to find God in all places or at all times. So thank God for the thin places that I stumble upon. And thank God for the interesting piece I stumbled on in the Times a few weeks ago – sitting in a simple guest room overlooking the melting water of Lake Sagatagan, wondering if in fact there is such a thing as coincidence.