One of the goals of The Jesuit Post is to create content that can be used in high school and college classrooms. The “Return to the Classics” series is one way we aim to fulfill that goal. Every year, thousands of students at Jesuit schools read a selection of the classics of Western literary, philosophical, and theological traditions. “Return to the Classics” provides a Jesuit perspective on these works, steeped in Ignatian Spirituality.

If I were to ask a classroom of boys if they would want to be a Greek war hero like Achilles or Spartacus, I would wager that the majority of hands would shoot excitedly into the air. At least, the high schoolers I taught in an early stage of my Jesuit formation might contrive reasons why they might even best these legends in a fight.

But I suspect that these teens would not know what they are getting themselves into. While contemporary movies such as Troy or 300 celebrate these ancient gladiators’ bravery, their source texts develop characters that are perhaps just as gorey and glorious but are far more nuanced. Because, in the end, we are a lot more like these legends than we might imagine.

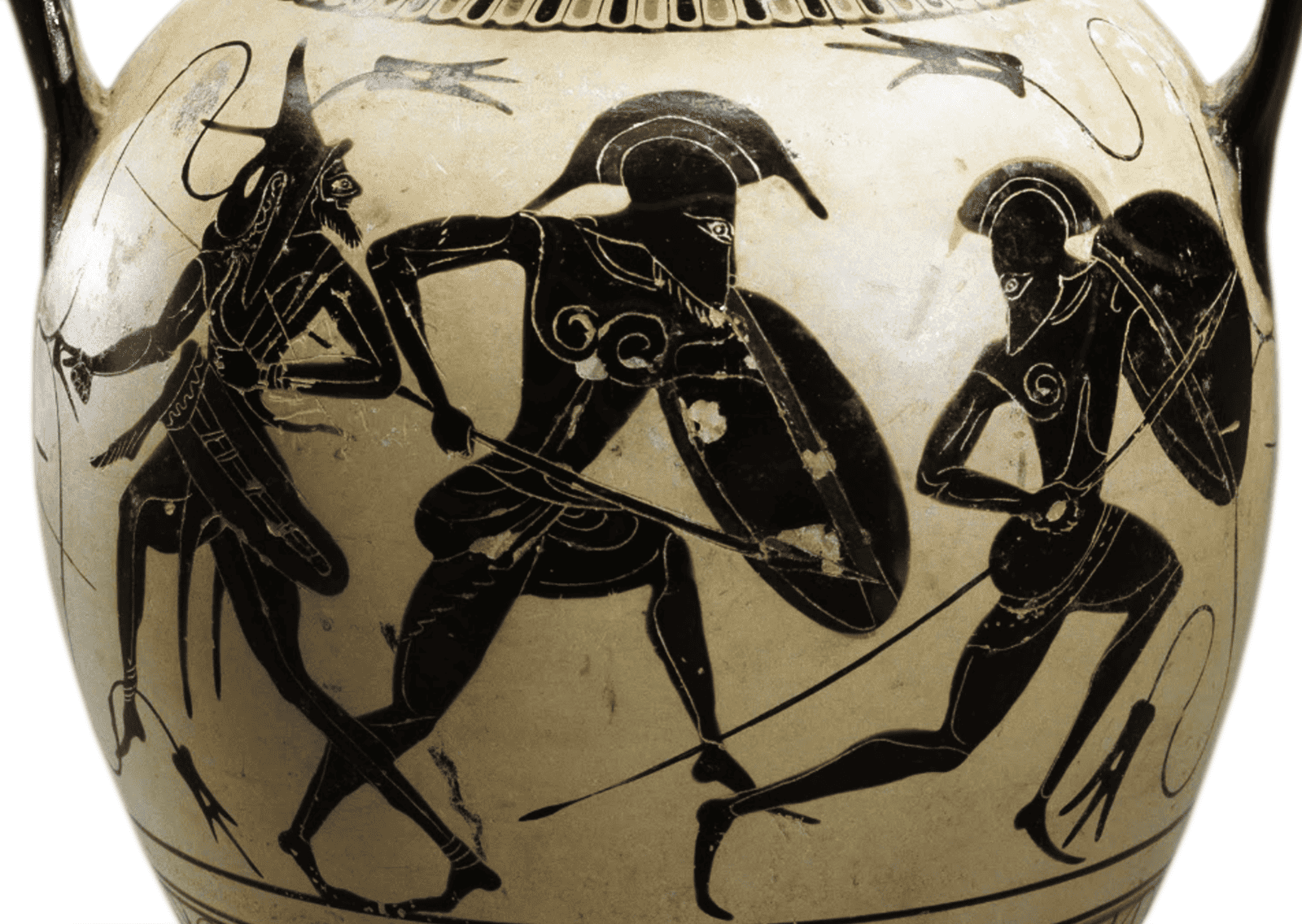

Homer’s Iliad tells the story of the Trojan War that has captivated imaginations for millennia. Yes, this is the conflict with the legend of the horse. And no, the Iliad does not recount this fabled military tactic. Instead, this epic poem focuses on the harrowing back-and-forth fight between two great armies whose fates are sealed by the petty and petulant gods. In a beautiful dactylic hexameter that is lost in translation, Homer vividly portrays the courage and costs inherent to hand-to-hand combat.

The story does not conclude with Greek triumph or defeat, however. The story centers on the intertwined fates of two of the most revered gladiators in antiquity: Achilles and Hector. The great Achilles is prophesied by his divine mother to live a short life full of fame and glory. Meanwhile, the equally mighty Hector carries the fate of his entire city on his shoulders. His rise or fall is told to be the survival or demise of thousands.

We all know the name Achilles, whether from the knowledge that he and the Greeks ultimately triumph or from the precarious tendon. Accordingly, we might anticipate that Achilles is the classic good guy. That he has pure motives and no flaws (apart from his heel). In contrast, Hector then is the stereotypical villain, defending an unjust cause and all-around plain despicable. At least, this line of thinking is reinforced by our favorite heroes like Spiderman and Hermoine Granger and renowned villains like Cersei Lannister and Emperor Palpatine. However, the Iliad’s heroes are far more complex and thus are perhaps the best protagonists and villains in all of fiction.

Yes, Achilles is a hero. But his tragic flaw is his uncontrollable rage. In fact, the opening line of the massive tome clues the reader into the centrality of this weakness: “Sing, Goddess, Achilles’ rage, black and murderous, that cost the Greeks incalculable pain, pitched countless souls of heroes into Hades’ darks.” Early in the story, the leader of the Greek army King Agammenmon denies Achilles his war-prize mistress Briseus. In response, Achilles fumes in his treasure-laden boat all while casually strumming his lyre while countless Greek soldiers are killed with his absence on the battlefield.

Our great hero subsequently appears more concerned with his honor than with his peers’ human life. Several Greek commanders attempt to persuade Achilles by appealing to the love of soldiers’ families back home and to his duty to his nation, but he remains resolute. Only the desire to avenge the death of his dear friend Patroclus impels Achilles to return to the skirmish.

And no, Hector is not a one-sided villain. Indeed, his unwavering pride leads to his death. His family and the King of Troy entreat Hector to fight Achilles another day when the odds might be in their favor. Still, Homer deftly tinkers with the reader’s sympathies. In one of the most tender scenes of the story, the mighty Hector shares a tender embrace with his baby son who had initially started to cry when he saw his father in his imposing war helmet. Hector then sets the helmet aside and spends a moment, not as a hero, but as an affectionate father with his small family. Hector’s steadfast commitment to the protection of his townspeople and loved ones stands in stark contrast to Achilles’ apparent selfishness.

Why does Homer develop his heroes this way? Why does he make his hero Achilles seemingly less perfect while painstakingly humanizing Hector? With three thousand years separating Homer and today, it is impossible to conclude definitively. To me, though, Homer nuances his characters to offer rich insights about humanity. Unchecked emotions might impede decision-making. Our enemies are still human persons who love deeply and are loved by others. And, above all, even the best of mankind (apart from Jesus) is not a god, no matter how hard we might try to grasp for perfection.

Homer stresses that humanity is a mixed bag: good and bad, errors and triumphs, love and loss. The story of the fall in Genesisーwhich might have been written down around nearly the same time as the Iliadーshares the same message. Although Adam and Eve ate from the Tree of Knowledge, humans are not God. Due to original sin, we disobey, we fall for the enemy’s tricks, and we can convince others to go along with our perhaps well-intentioned yet misguided plans. Even the heroes of the Old Testament like Noah and King David yielded to temptation and sinned.

This focus on humanity’s flaws might come across as discouraging. Are we fated, like our Greek heroes, to destruction and demise? Absolutely not! Recognizing our imperfections is not just good news, it is intrinsic to the Good News. A core message of the Gospel is that we believe in a God who loves us so much that he sacrifices His only son as expiation for our sins. Paul summarizes this best in his letter to the Romans: “Indeed, only with difficulty does one die for a just person, though perhaps for a good person one might even find courage to die. But God proves his love for us in that while we were still sinners Christ died for us” (Romans 5:7-8).

As Christians, we can admire the bravery and talent of Hector and Achilles, but we have a better paradigm of what it means to be human: Jesus Christ. The Greek heroes risked their lives for their own pride and ego, all the while leaving a path of wanton destruction and death. Conversely, Jesus offered Himself for others, for us sinners. The followers of His Way do not live for themselves but rather the Kingdom.

Accordingly, Ignatius organizes the four weeks of the Spiritual Exercises by beginning with a reflection on sin. The retreatant ponders how sin entered humanity and then how personal sin has affected their life. The objective is not to despair at humanity’s brokenness but rather to accept that humanity cannot achieve perfection on its own. But the Second Week shows us that there is another way to live in the footsteps of Jesus Christ. The Third Week then brings us to the foot of the Cross, with the Fourth Week then culminating in contemplating God’s cosmic love for the world. Sin does not have the final word in God’s story nor ours.

Accepting our flaws is also simply good for us as human persons. When I accompanied those aforementioned audacious high school men, I was astounded by the amount of pressure many of them felt: the pressure to please their parents, to fit in at school, to perform well in sports, to afford college, and so on. One student, in particular, struggled on a test. Over the next few days, I could tell that he was fixated on his grade, so I told him that test corrections are more important to me. After all, I said we tend to learn more in the long run when we correct our mistakes and not regurgitate some memorized facts on paper. A visible weight was lifted from his shouldersーand he outperformed on the final exam.

Something about our human nature wants to ace the test on the first try. We believe in the illusion that we can be perfect. Some might even strive to be a god. Inevitably, though, we will fail. We break our New Year’s resolutions and Lenten sacrifices. We give into temptation and pass along gossip or accidentally hurt a loved one.

When we deny this part of our nature, we not only set ourselves up for failure but also fail to accept the immense love and grace that Jesus offers. Christians profess faith in a God who loves us perfectly even though we may not always be perfect. Indeed, we are like Achilles and Hector in that we are a mix of good and evil, of love and sin, of will and temptation. But that is Good News.

Author’s Note: Thank you to Fr. Michael McCarthy, SJ for first introducing me to the classics through the Iliad. Without your passion and enthusiasm, I would not have considered how these ancient texts hold timeless wisdom for me today.