Last weekend, nearly 2000 students came to Washington, D.C., in the name of a faith that does justice. These students attended the Ignatian Family Teach-In for Justice, the largest annual Catholic social justice gathering in the United States. This conference brings together students from Jesuit high schools, universities, and parishes, as well as other groups with an affinity for the Ignatian tradition and social justice. The Teach-In incorporates dynamic national speakers, informative workshops on a variety of social justice issues, moving prayer experiences, and caps off with participants speaking with legislators on Capitol Hill.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the Teach-In, hosted by the Ignatian Solidarity Network. The first Teach-In was hosted under a tent in Fort Benning, Georgia, and protested the School of the Americas, which trained many of the Salvadoran soldiers responsible for the murder of six Jesuits and two women at the Central American University (also known as U.C.A. El Salvador). These Jesuits were outspoken against the government for injustices against the poor and vulnerable. The original Teach-In sought to bring attention to these injustices and encourage response through prayer and demonstration.

Today, the Teach-In has moved to Washington, D.C., and incorporates a variety of social justice issues. Though some things have changed, at its core, the Teach-In remains committed to bringing to light injustices in the world today. Participants still draw inspiration from the Salvadoran martyrs, whose pictures line the main stage and are the focus of a prayer service held on the opening night of the conference each year.

It is fitting that at this year’s Teach-In, celebrating 25 years of gathering, there was a persistent theme of recognizing the work and experiences of those who have gone before us, as well as the need to collaborate in the work that still needs to be done. The legacy of our past can inform us on how we work to build a better world. These themes were present in the talks by each of the main presenters.

Bill McKibben: The fight for climate justice must be intergenerational

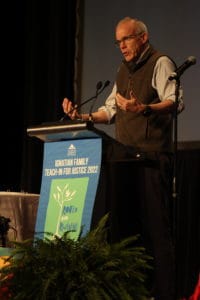

Bill McKibben was the first keynote presenter to take the stage. McKibben is a climate activist, a contributing writer to The New Yorker, and a founder of Third Act, which organizes people over the age of 60 to work on climate and racial justice. He also founded the first global grassroots climate campaign, 350.org.

Bill McKibben was the first keynote presenter to take the stage. McKibben is a climate activist, a contributing writer to The New Yorker, and a founder of Third Act, which organizes people over the age of 60 to work on climate and racial justice. He also founded the first global grassroots climate campaign, 350.org.

McKibben reminded participants of the ongoing climate crisis, made evident by natural disasters that often affect the poor and vulnerable. He also marveled at the advances that have been made in renewable energy as well as our reluctance to embrace these technologies as a society.

McKibben lauded the efforts that have been made by the younger generation in fighting climate change and commended the audience for what they have done and what they are capable of doing. He warned that this should not get the older generation off the hook. There is a tendency to want to hand off the climate crisis to the next generation, but that has been the problem with climate change all along. The older generations have a certain among of power and resources in the country and that must be used to back up the efforts of the younger generation. This has to be something that we do together.

“You need older people too! You know what old people do? They vote, and in large numbers. Old people also ended up with most of the money. If you want to take on congress or Wall Street, you want some old people backing you up.”

******

Michael O’Loughlin: A Hidden Legacy of Mercy

Michael O’Loughlin was also present for an event for young adults at the conference. O’Loughlin is a contributor at America Media, author of Hidden Mercy: Catholics, AIDS, and Untold Stories of Compassion in the Face of Fear, and host of the award-winning podcast “Plague: Untold Stories of AIDS and the Catholic Church.”

In this conversation-style presentation, O’Loughlin talked about the subject matter of his book and podcast, which is the history of the Catholic Church responding to the AIDS crisis. He spoke of his own desire as a gay Catholic to learn more about the compassion that members of the Church showed the LGBTQ community during the AIDS epidemic. O’Loughlin’s shared the stories of Catholics like Fr. Bill McNichols and Sr. Carol Baltosiewich, who both responded in different parts of the country and in very different ways to care for those who otherwise felt alone and abandoned.

In this conversation-style presentation, O’Loughlin talked about the subject matter of his book and podcast, which is the history of the Catholic Church responding to the AIDS crisis. He spoke of his own desire as a gay Catholic to learn more about the compassion that members of the Church showed the LGBTQ community during the AIDS epidemic. O’Loughlin’s shared the stories of Catholics like Fr. Bill McNichols and Sr. Carol Baltosiewich, who both responded in different parts of the country and in very different ways to care for those who otherwise felt alone and abandoned.

One of the greatest gifts of O’Loughlin’s work is bringing to light the hidden legacy of Catholics working with great care and compassion for and with the LGBTQ community. This legacy can help inform and motivate Catholics today as we continue to learn how to care for this community.

******

Maka Black Elk: Recognizing the stories of the past in order to bring healing and reconciliation

Maka Black Elk took the stage for the second keynote of the Teach-In. Maka is the Executive Director for Truth and Healing at Red Cloud Indian School on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. Red Cloud is one of the few remaining Jesuit schools serving an indigenous community in the country.

Maka Black Elk took the stage for the second keynote of the Teach-In. Maka is the Executive Director for Truth and Healing at Red Cloud Indian School on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. Red Cloud is one of the few remaining Jesuit schools serving an indigenous community in the country.

Maka addressed the tragic history of Native American boarding schools and the Catholic Church’s involvement in some of these schools. Part of the purpose of the Truth and Healing Project is to bring to light the stories of those who experienced trauma from these schools. He shared powerful stories of individuals who were estranged from their families and made to feel ashamed of their Indigenous identity as students of these schools.

“What is Truth, Healing, and Reconciliation as a process? There is not one answer. It’s something that individuals, organizations, or even nations can go through to heal from great harm. We do this first by examining the truth.”

Maka Black Elk also talked about his Catholic faith as an indigenous person. “I am indigenous and Catholic. It might seem illogical that both of those things are true.” He reminded the audience that the historical Catholic Church and the faith itself are not always the same thing. We can and must recognize the atrocities that have been done in the name of faith, while recognizing that is not the faith itself. “What happened to indigenous peoples in the boarding schools was not of the faith. They were acting against the faith. There is no excuse for that.”

What does healing from this past look like? Maka said that healing is a personal journey and that will look different for each person. We cannot make people heal, but we are responsible for providing the things that people need to heal. “We have to believe that healing is possible and that we can want to heal. We also have to believe that we are worthy of healing.”

******

Olga Segura: Black Lives Matter and the Catholic Church

The final keynote of the weekend came from Olga Segura. Segura is a freelance writer and author of Birth of a Movement: Black Lives Matter and the Catholic Church. She was previously the opinion editor at the National Catholic Reporter and an associate editor at America Media.

The final keynote of the weekend came from Olga Segura. Segura is a freelance writer and author of Birth of a Movement: Black Lives Matter and the Catholic Church. She was previously the opinion editor at the National Catholic Reporter and an associate editor at America Media.

Segura’s work is grounded in the conviction that every single person deserves to have their needs met and that we must recognize the communities for whom this is a struggle. People of Color continue to be the target of profiling and marginalization and although our Catholic faith calls to work against such injustices, we must also recognize the ways in which our faith has perpetrated this marginalization. “My Catholic faith demands that I name and confront white supremacy and the role Christianity has played in sustaining it.”

Similarly to Maka Black Elk, Segura proclaimed the importance of recognizing the truth of the injustices that have been perpetrated against people in our society as a path towards healing and bringing about justice. This is why she has focused much of her reporting and her book on the Black Lives Matter movement since it “taught an entire generation how to imagine, fight for, and build a world that refuses to cosign human beings and other beings to disposability.”

Segura shared how these movements taught her to be Catholic and appreciate her Catholic faith, a faith that calls us to solidarity and to seek justice, especially for the most vulnerable. What does solidarity look like for White Catholics? First, it must include a dialogue around power: who has it and who does not. Many people have engaged in these conversations, especially in the past few years, but it cannot stop there. Power must be confronted and work must be done to center those who have been left at the margins of society.

“White allies must ask themselves: What are some of the immediate ways that I can help? What are some of the long-term ways that I can help? What are some ways I can use my privilege, access and resources to center and support marginalized women, men, and children? How can I hold myself accountable while we think through strategic ways to work toward liberation? And how can I do this work without placing the burden on People of Color?”

******

A Faith that Does Justice

There are many more presenters and speakers who were part of the Teach-In this year, each presenting on the realities of injustices in our world, but also the hopeful ways in which people are working to bring about justice and the Kingdom of God. The beauty of the Teach-In is that it brings together so many people from all over the country who are motivated by their faith to work toward justice. The work might take time and even expand over generations, but it is work that we do together. The Teach-In is a powerful reminder that we are not alone.

The Ignatian Family Teach-In models the best aspects of our Catholic faith. We gather to recognize that we are a community, bound by faith and love. We engage in instruction and teaching as we learn about problems in our world and how we might respond. We pray together for strength, forgiveness, healing, and unity. Finally, we put our faith in action by speaking to those in power and returning to do important work in our communities.

Here’s to another 25 years of bringing people together to live out a faith that does justice.