Last year, The Jesuit Post started the “Jesuit 101” series in honor of the Ignatian Year. This year, we want to continue this series and focus on the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Loyola, the heart of the Jesuits. We will explore a different aspect of the Spiritual Exercises each month with an explainer article and reflections or real-world applications for each topic. We begin with the First Week of the Spiritual Exercises.

How to Understand the Spiritual Exercises

The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius is the foundation of Ignatian Spirituality. The Exercises are divided up into four “weeks” or parts, each with its own purpose and theme. In the first week, the person undergoing the exercises, the “retreatant,” meditates on the reality of sin and our human need for a savior. However, in order to understand any part of the Exercises, including the First Week, one must know and embrace the “First Principle and Foundation.”

In a word, that foundation is that human beings are made to praise, reverence, and serve God in this life so that they may enter into eternal life with him in the next. Everything an individual thinks, says, or does should be ordered to this end, even if that means they have to embrace poverty, sickness, dishonor, or a short life. This foundation is meant to accomplish the goal of the Spiritual Exercises, which St. Ignatius says is “the conquest of self and the regulation of one’s life in such a way that no decision is made under the influence of any inordinate attachment.”1 In other words, the First Principle and Foundation is meant to cultivate interior freedom in the retreatant.

Once the retreatant embraces that foundational principle, they’re ready to enter into the First Week of the Exercises.

The Particular and the General Examination of Conscience

The first part of the First Week provides a framework for making a daily “particular” examination of conscience, as well as a framework for making a “general” examination of conscience. The particular examination is meant to help the retreatant root out particular temptations and sins with which they struggle—a key move in fostering interior freedom. The general examination provides the outline of what will eventually become the popular “Ignatian Examen.”

In the section for the general examination of conscience, Ignatius distinguishes three kinds of thoughts in a person’s mind: one that is the person’s own and arises entirely from their free will, and the two others as coming from either the good or the false spirit. In other words, the other two sources of our thought are from God’s spirit of love or from the evil spirit of deception and destruction that is at work in the world. This recognizes not only the existence of good and evil forces in the world, but that they can also have some sort of influence on our thoughts. It is important then to grow in awareness of these influences through this examination. Another way of thinking about it is to trace the source of our thoughts. Are they rooted in love and are life-giving or are they rooted in selfishness or anger and lead one into darkness? Which of these thoughts do we dwell on and what effect do they have on us and our actions?

After distinguishing three kinds of thoughts, St. Ignatius then parses out the thoughts, words, and actions which constitute either venial or mortal sins.2 Why would Ignatius begin the Exercises by focusing on examining our conscience? Why begin a spiritual retreat by focusing on sins? The answer to those questions is found by looking at the graces we pray for during the First Week.

The Grace of Shame and Confusion?

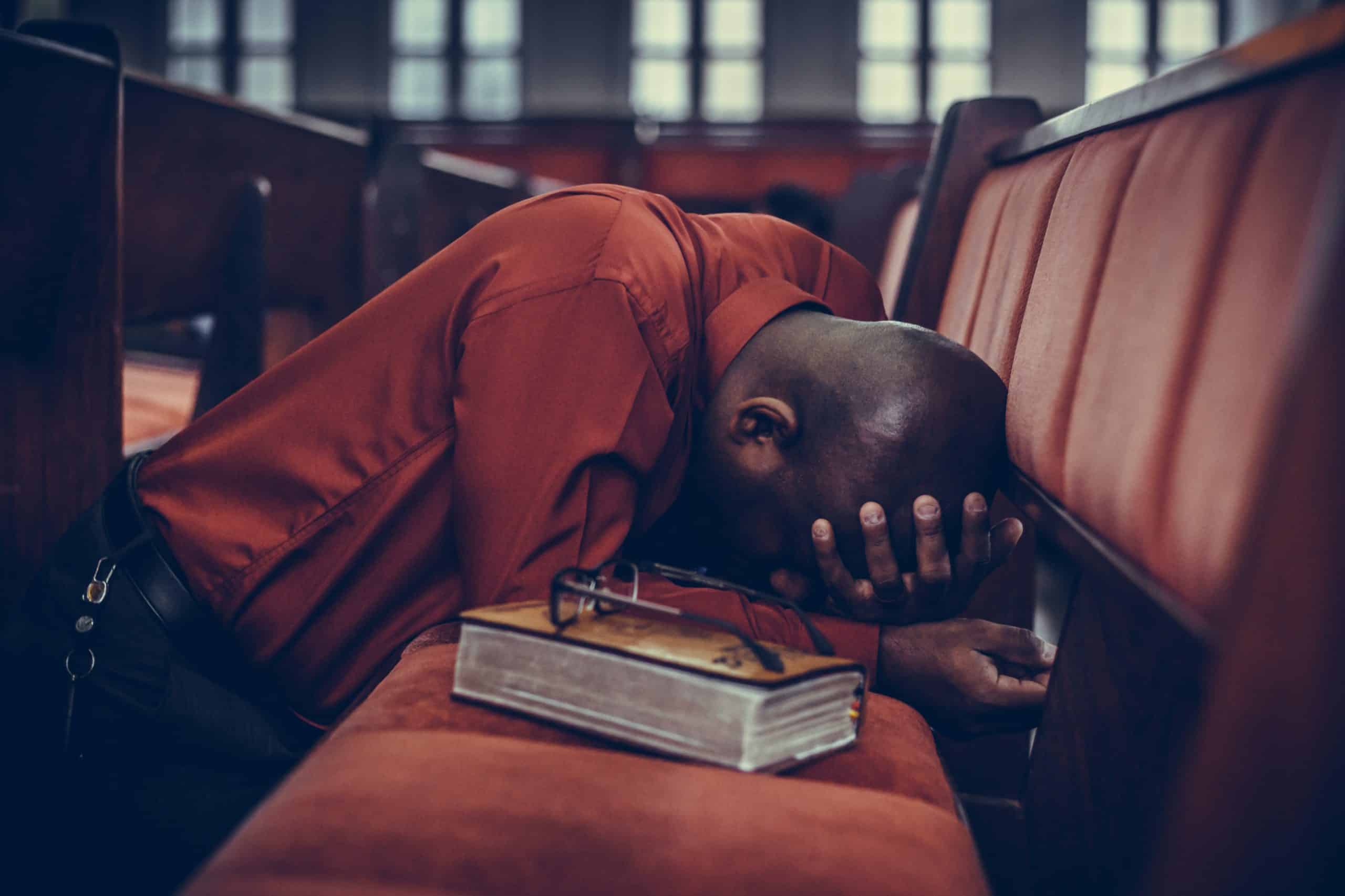

The meditation on sin in the First Week starts with meditating on the sin of the angels, the sin of Adam and Eve, and the sin of a person suffering the torments of hell. Retreatants are directed to pray using the “three powers of the soul,” which are memory, understanding, and will. They’re to use the memory to recall the story or scenario of each of the events above, their understanding in order to think more deeply on the matter, and their will so as to stir their affect.

Ignatius advises that the grace the retreatant should pray for in this meditation is to experience “shame and confusion” because of their sinfulness. That may sound like a shocking thing to pray for, so what is Ignatius getting at?

Recall the purpose of the Spiritual Exercises: having interior freedom to consistently choose God’s will in our lives. If we’re going to seriously pursue this goal, then we need to confront the reality of sin, since that is the very thing that will stop us from attaining that end. Sin to the soul is like an injury to the body. If we ignore that injury or pretend that it doesn’t exist, it will almost always get worse. This is true not just for individual sins, but for what are called “social sins” as well. The sin of racism is an obvious example, which is why confronting structural corruption and injustice is a “first week experience.”

Even if we recognize the need to confront sin, we may still wonder why we’re praying for the grace of “shame and confusion.” After all, aren’t these bad things in and of themselves? It’s helpful to focus on both the nature of sin and the “three powers of the soul” in order to know how we might benefit from the grace of shame and confusion.

The Old Testament Hebrew word for sin (‘khata’) literally means to “miss the mark or goal.” Sin, then, is to forget the First Principle and Foundation. It’s to place someone or something other than God at the very center of our lives, thus forfeiting the most important component of our spiritual lives: gratitude. Ignatius wrote in a letter, “of all the imaginable evils and sins, one that merits the loathing of our Creator and Lord and of every creature capable of his divine and everlasting glory is the sin of ingratitude, being as it is the refusal to acknowledge the goods, graces, and gifts that we have received, and so the cause, principle, and source of every evil and sin…”

Now, in the course of remembering all the good that God has done for us, which is a common thread running through all of Sacred Scripture (especially in the Psalms), then how can a person not feel shame for the ingratitude inherent in turning away from the Lord? And if we truly understand the First Principle and Foundation of our lives, yet still we will something other than God’s vision for our lives, how can we not be confused? Simply put, sinning doesn’t make sense. It’s easy to understand this when sin is particularly egregious, like in the case of someone murdering a person in cold blood. That’s something that we can’t rationalize. But what’s true in that case is fundamentally true for all sin—in the light of our purpose as creatures created and destined for eternal life with God, sin isn’t reasonable. So we pray for the grace of shame and confusion at the presence of sin in the world and in our hearts.

Sin and the Love of God

The final movement of this prayer in which we ask for this terrible grace points us out of that darkness. Ignatius directs us to imagine Christ our Lord before us on the cross, and to ask him why he would do such a thing as become a human being and die for our sins. Of course, there is only one answer to that question: “For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him might not perish but might have eternal life.”3

This is really the fundamental grace of the entire First Week. We confront our sin—we stare it in the face in all its horror and shame—in order that we might know that God has loved us and will love us through it all. St. Paul may not have undergone the Spiritual Exercises as such, but it’s this very First Week grace that allowed him to write, “For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor present things, nor future things, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.”4

Pope Francis embodied this grace when he was asked by a reporter, “Who is Jorge Mario Bergoglio?” Pope Francis responds, “I am a sinner. This is the most accurate definition. It is not a figure of speech, a literary genre. I am a sinner.”

After asking Christ on the cross why he would suffer for us and seeing that it can only be because he loves us, we are then directed to ask a threefold question: “What have I done for Christ? What am I doing for Christ? What will I do for Christ?” Just like Pope Francis has made mercy central to his pontifical mission because he knows what it means to be a loved sinner, so we too are called to make a response of love after we embrace God’s mercy.

The End of the First Week with Christ the King

Finally, the meditation known as “The Call of Christ the King” is a bridge between the first and second week of the Spiritual Exercises. Ignatius directs us to first imagine a political ruler who makes all the promises politicians make (everyone will be fed and have a roof over their heads, injustice will be rooted out, sickness and disease will disappear, etc.). But this ruler, Ignatius says, is able to actually accomplish everything they promise. The only condition on our part is that we imitate this ruler in everything. We wear what they wear, speak how they speak, eat what they eat, and so on. What sane person wouldn’t follow such a leader? The second movement is that if we are so willing to follow a merely earthly ruler, how much more should we consent to follow Christ the King of the entire Universe, the one who is accomplishing and will accomplish everything that he has promised?

This final prayer perfectly prepares the retreatant to follow Christ in his earthly ministry all the way to Palm Sunday, which is the topic of the Second Week of the Spiritual Exercises. During that week, we see Christ speak to people. We see the way he treats the rich and the poor, the beggar and the soldier, the strong and the weak. And we strive to imitate him in our own life.

Do Not Be Afraid

With its focus on sin, the First Week can seem intimidating. But it’s important to reiterate that we only confront the reality of sin in order to embrace the much more fundamental reality of God’s mercy and love. One of the Jesuits’ governing documents frames it this way:

“What is it to be a Jesuit? It is to know that one is a sinner, yet called to be a companion of Jesus as Ignatius was…”

Anyone who has undergone the First Week of the Spiritual Exercises should be able to identify with the above statement. All of us have fallen short of the glory of God, yet all of us are called to become friends of the Lord and to follow him. That’s what the Second Week has in store.

- Spiritual Exercises annotation 21 ↩

- It is this part of the Exercises that actually got Ignatius in trouble with the Inquisition a couple times, since when Ignatius first started giving the Exercises to people, he hadn’t studied theology, nor was he an ordained minister. In order to prevent getting in trouble, Ignatius discerned that he should study theology and pursue priestly ordination. During his studies, he met Francis Xavier and Peter Faber, who would later co-found the Society of Jesus alongside their friend Ignatius. ↩

- John 3:16 ↩

- Romans 8:38-39 ↩