In her 2004 book Hope in the Dark, Rebecca Solnit presents a compelling model of humanity in crisis. In the aftermath of the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco, she recounts, individual people rose above their differences and formed the communities necessary to sustain life amidst the ruins. Dorothy Day famously lived through that frightening time as a child and noticed the way people reacted “as though they were united in Christian solidarity.” 1 Her response animated the rest of her life’s work: Why can’t we live like this all the time?

Solnit recounts how this pattern plays out in crisis after crisis, from Hurricane Katrina to the September 11 attacks. People on the ground rise up and respond wholeheartedly to their neighbors in need. Those in power, on the other hand, are prone to react in fear, preemptively arresting “looters” and cracking down on the organic communities that spring up. If only we trusted those responding from the ground, Solnit begs, we might create the Kingdom of God on Earth that Day envisioned.

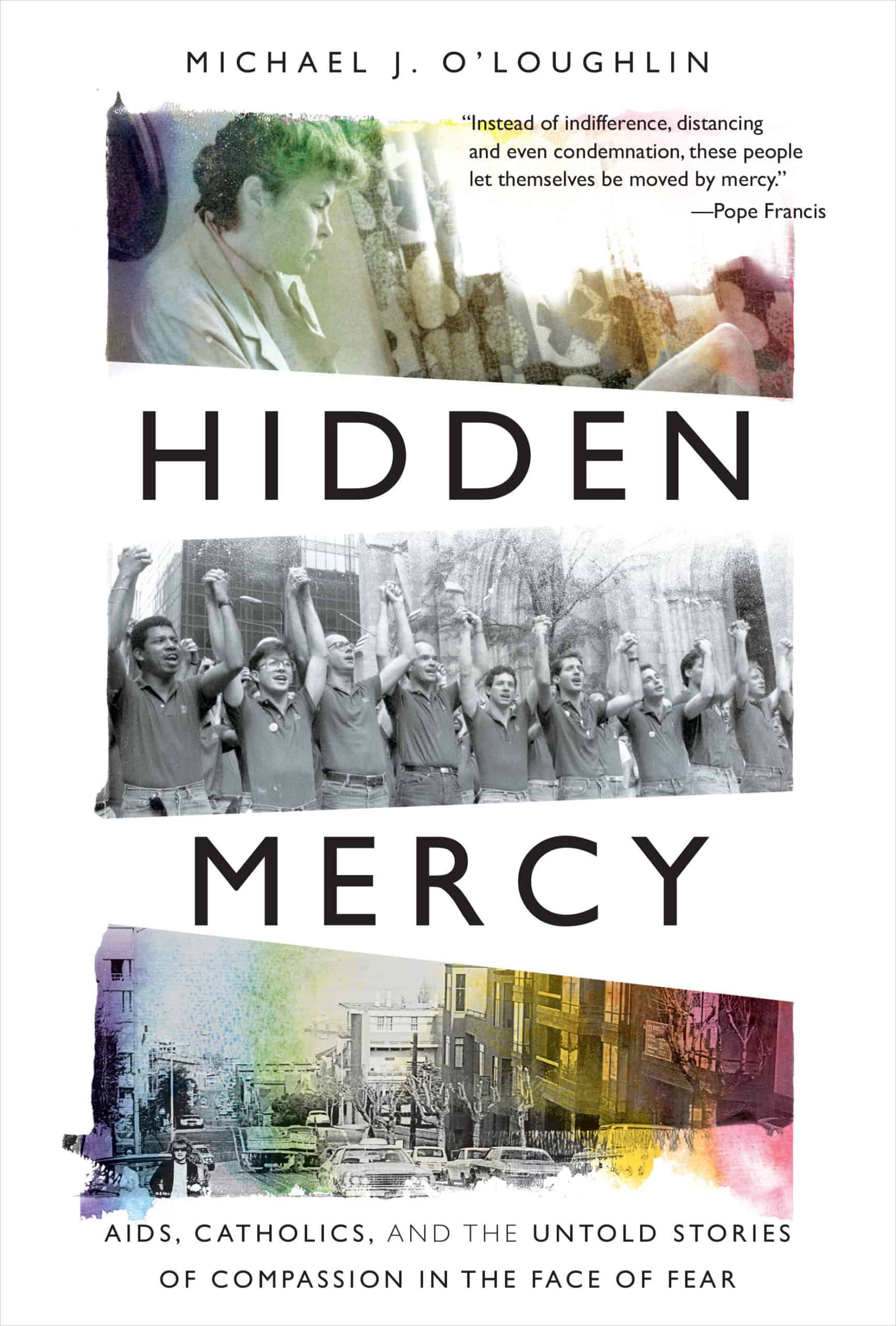

A new book adds further data points to Solnit’s thesis. Michael O’Loughlin’s Hidden Mercy: AIDS, Catholics, and the Untold Stories of Compassion in the Face of Fear recounts the story of those on-the-ground Catholics who persisted heroically in the face of the HIV/AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 90s. The book raises the same question Dorothy Day asked: Why don’t we, especially as Church, live like this all the time?

O’Loughlin’s history presents a narrative starkly in contrast to how the Church and the gay community exist in the popular imagination of these very communities. O’Loughlin doesn’t shy away from the more difficult parts of the history, including the infamous antagonism between ACT UP and various archdioceses. But O’Loughlin’s narrative doesn’t dwell on the headline stories. Instead, he brings to life various characters otherwise sidelined in mainstream retellings of the time.

The two characters he most vividly brings to life are a Catholic nun, Sister Carol, and a Catholic priest, Bill McNichols. Early in that pandemic, Carol was a Hospital Sister of Saint Francis working in Belleville, IL, when she was sent to offer hospice care to a young man whose professional ballet career had been cut tragically short by an HIV diagnosis. Heartbroken by the dramatic toll the disease took on his body, Sister Carol convinced her religious superiors to let her go to New York to learn everything she could about the burgeoning disease. Meanwhile, Bill was a Jesuit priest recently missioned to study art in New York City. Across the archdiocese, gay groups were being progressively shut out of parish activities. Angered by the bullying, Bill responds to the invitation of various gay groups to serve as a spiritual minister, eventually taking on a role as a hospital chaplain and helping to design numerous icons that became spiritual touchstones.

Around the stories of Bill and Carol, O’Loughlin paints a complex picture of how the Church responded to the last American plague. Catholic hospitals, parishes, and even cardinals heard the cry of the sick and ministered to them. Pastors and hospital chaplains and sister nurses labor in the vineyard. Meanwhile, upper level managers in the American and Universal Church offer edicts that feel profoundly detached from the reality on the ground, often actively impeding the holy work being done. Like the power structures Solnit identifies, the hierarchy seems afraid of what fruit the ministry might bear. Bishops prohibit gay Catholic groups from holding Masses in their moment of deepest mourning. Meanwhile, older, traditional Catholic women in the Castro have their hearts opened by the young men dying and start a hospice in the neighborhood (complete with a very Catholic Bingo fundraiser!).

In addition to the numerous stories which O’Loughlin has rescued from the mists of time, he shares his own journey as a gay Catholic. Until now, the heroic work of Sister Carol, Father Bill, and so many others has gone mostly underreported, so the oppositional narrative has won the day. As O’Loughlin writes, to exist as a gay person the Church can be a “complex reality” without a clear playbook to reconcile the differences.

The stories in Hidden Mercy present a Gospel model of reconciliation. Jesus responds to need, and at our best, we imitate him and allow ourselves to be formed. Sister Carol admits she might never be comfortable talking about gay sex, but after watching a young man tend to his dying lover, she asks “Why is this wrong?” Father Bill experiences his hospital chaplaincy as a moment of healing from forced conversion therapy he had undergone as a young man. In San Francisco, an Archbishop finds his eyes opened and heart moved by the experience of spending time in a parish that had mobilized to help those dying of AIDS. Hearts are not moved and healed and changed by theories and philosophies, but by the response to tangible need in front of us.

Dorothy Day was a sort of patron saint for many who stood with the gay community during the AIDS crisis. In her lifetime she was reticent to discuss homosexuality, finding it taboo. Regardless, numerous Catholic worker houses were established to care for those suffering from HIV/AIDS. The greatest strength of Hidden Mercy is that it savors people’s uncomfortable humanity. O’Loughlin isn’t content to paint with broad strokes the heroes and villains of the story. Instead, he presents for us people as they actually exist, with existential doubts and imperfect ideas and numerous mistakes. Using these imperfect actors, God was made manifest for thousands of young men dying of AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s through loving Catholics responding to the needs in front of them.

Why, O’Loughlin seems to ask, can’t we respond like this all the time?

-//-

Hidden Mercy is available from Broadleaf Books and wherever books are sold.

- Dorothy Day, The Long Loneliness ↩