“Where were you when the blast happened?” It’s a new question added to the plethora of salutations and well wishes that usually season conversation here in Lebanon. The reference is, of course, to the Beirut blast which happened six months ago at 6:07 PM. Forgive the specificity, one of our clocks stopped ticking at the moment of the blast and we haven’t yet replaced it.

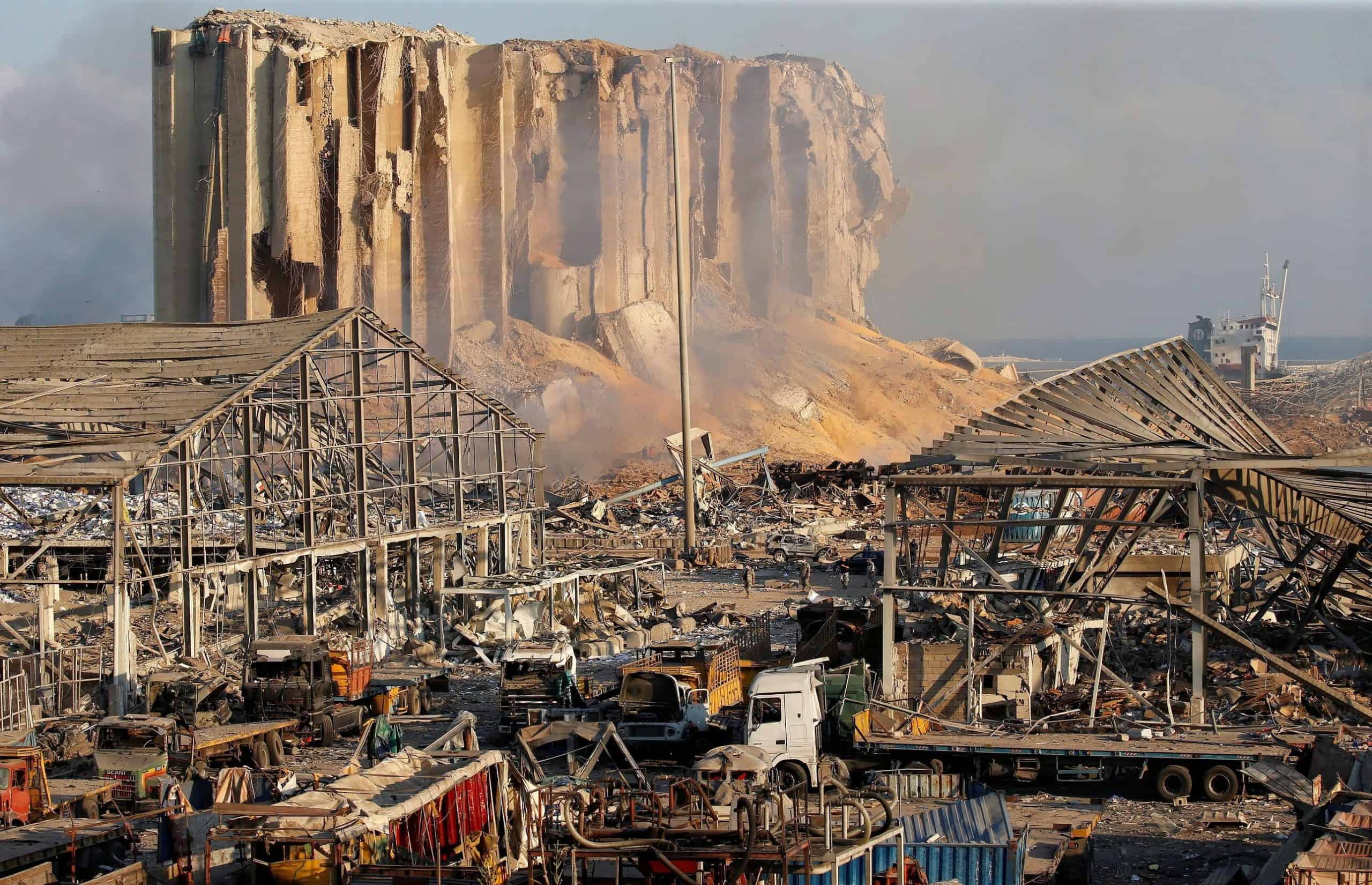

In a few seconds, carelessly stored ammonium nitrate at the city’s port devastated Beirut in a way that decades of civil war could not. More than two hundred people perished, thousands were injured, and an entire city sunk into a pit of shock and anger.

When I arrived, a few weeks after the explosion, I witnessed a post-apocalyptic scene of shattered glass and strewn debris. Yet, there have also been many invisible wounds. In my work with the Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS), I’ve listened to our psychologists and social workers tell stories of traumatized children who refuse to sleep next to windows. I’ve seen grown men and women crouch in fear at the sound of thunder. Many of the Palestinian and Syrian refugees (estimated at 170,000 and 1 million respectively), live in areas badly damaged by the blast.

Many refugees have shared that the blast triggered memories of the circumstances that led them to leave home. The tragedy of the blast has been compounded by an economic crisis (the value of the currency has declined by 80%), a political stalemate (no functioning government), and a surge in COVD-19 cases that has utterly overwhelmed the hospital system.

It’s from this vantage point that I’ve been listening to Pope Francis’s calls to grow in fraternity, especially via Fratelli Tutti and the various overtures that he has made towards those of other religious faiths. Indeed, Pope Francis notes that his 2019 meeting with the Imam of the Al-Azhar mosque in Abu Dhabi served partly as the inspiration of Fratelli Tutti.

The legacy of the meeting also continues today through International Human Fraternity Day, which was celebrated yesterday. Pope Francis is also planning on meeting with the foremost religious authority in Shia Islam, Grand Ayatollah of Iran, Ali al-Sistani, when he visits Iraq next month. These gestures are really quite profound in Lebanon, where the confessional structure of the government (the President has to be Maronite Christian, the Prime Minister, Sunni, and the Speaker of the House, a Shia) makes religion and politics very difficult to separate. In such a climate, religion can sometimes appear to be a source of division.

In Fratelli Tutti, however, Pope Francis suggests that suffering can be a locus where those of different faiths can connect. Using the example of the Good Samaritan, he proposes:

Jesus asks us to be present to those in need of help, regardless of whether or not they belong to our social group. In this case, the Samaritan became a neighbour to the wounded Judean. By approaching and making himself present, he crossed all cultural and historical barriers. Jesus…challenges us to put aside all differences and, in the face of suffering, to draw near to others with no questions asked. I should no longer say that I have neighbours to help, but that I must myself be a neighbour to others.

The Good Samaritan is only one image of compassion. Another possible image is the hospitality of Abraham and Sarah (Genesis 18), a story shared across Islam, Judaism, and Christianity. Three strangers approach Abraham as he stands at the entrance of his tent. Then, as now, hospitality can be a matter of life or death in the Near East. Abraham moves towards the strangers, welcomes them, and entertains them while Sarah generously prepares a meal. In the very carnal actions of feeding the hungry, and making themselves available for conversation, Abraham and Sarah find that their relationship with the strangers and with God unfolds in tandem.

Religion does not limit itself to the fuzzy stuff. We’re also heir to the often violent narratives that surround the formation and continuation of religious communities as they differentiate themselves from their neighbours. Divine election can often be accompanied by genocide, imperial enforcement of orthodoxy, and conversion by compulsion. Yet, we always have a choice of what images of God and neighbour to hold. Pope Francis is inviting us to pay special attention to those narratives within our respective traditions that foster hospitality and allow us to receive each other in charity.

When I look at the moments of consolation amidst the darkness that I’ve experienced here in Lebanon, I think that I get a sense of what the Pope means. In my work with JRS, I’ve been struck by the communities that form around suffering. Our staff and beneficiaries come from Sunni, Shia, and Christian traditions. We have Syrians, Lebanese, Egyptians, Jordanians, Iraqis, and Americans, who work side by side. Of course tensions and differences exist, and we acknowledge them. We also experience ourselves as connecting with a far more fundamental reality.

This reality is beautiful, dizzying, and terrifying. It’s the knowledge that we are all wanderers and stand in need of respite from the harshness of the desert. It impels us to see the angelic in the stranger, the messenger who reveals the uncomfortable truth of our fragility and yet invites us to grow through fraternal service. It is the possibility that even amidst the crunch of broken glass, we can hear the faint but steady call to trust that our meanderings trace out a path to a shared home.