I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

Like many Americans, I grew up with an inadequate understanding of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. In Catholic grade school, we heard snippets of the “I have a dream” speech and offered vague prayers for racial harmony during February. In high school, I began hearing classmates’ whispers aimed at undermining his legacy. In college, MLK Day meant committing to peace and service. Not until graduate school did I gain a fuller understanding of his teachings, actions, and legacy.

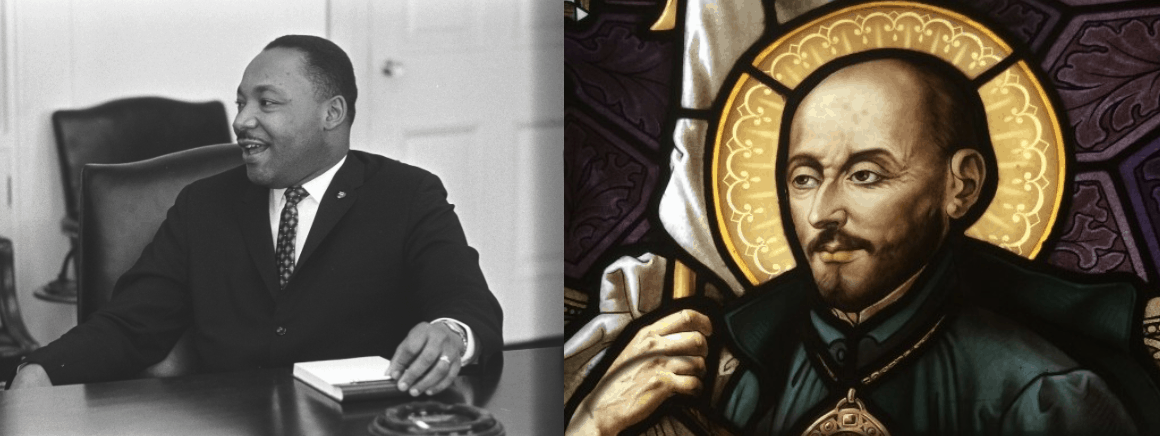

I recently read Dr. King’s book Where Do We Go From Here? It has shaped my understanding of Ignatian spirituality and its relationship to racial justice. Here are three lessons that MLK and Ignatius taught me about discernment and anti-racism.

Discernment and Freedom

What is freedom? It is, first, the capacity to deliberate or to weigh alternatives…Second, freedom expresses itself in decision…A third expression of freedom is responsibility…The immorality of segregation is that it is a selfishly contrived system which cuts off one’s capacity to liberate, decide, and respond.

King’s words on freedom sound quite like those of Ignatius. Ignatius spoke of freedom as being opposed to disordered attachments. We must cast off our attachments in order to freely discern God’s call. Doing so enables us to make decisions true to the Gospel.

It is a disappointment with the Christian church that appears to be more white than Christian, and with many white clergymen who prefer to remain silent behind the security of stained-glass windows.

Ignatius and MLK rightly identified fear as one of the greatest disordered attachments. A longing for a sense of security inhibits a movement toward God and justice. Elizabeth Eiland Figueroa states that “this clutching does not allow much space for God. Fear tells us that if we lessen our grip, chaos will ensue.” I constantly see arguments against racial justice, reparations, and liberation framed in terms of possibly dangerous consequences or an allied group not perfectly aligning to Church teaching. These arguments desperately cling to power and comfort, hiding behind the security of stained-glass windows.

In the Spiritual Exercises, Ignatius has the retreatant pray about three categories of people. Each has acquired a significant amount of wealth (not necessarily by wholesome means) and desires to part with it to save their soul. The first postpones until their death, deeming other things more important. The second rationalizes and deceives themself into believing that God wants them to keep their wealth. The third asks to be free from the attachment to the wealth, to do with it whatever God asks.

White privilege and white supremacy are particularly insidious because the attachment is often to comfort, social standing, or claims of social innocence with no awareness of their connection to whiteness and racism. Attachment to white privilege and white supremacy leads to an inauthentic faith. They are not open to the power of God’s justice. For me as a white man, Ignatian anti-racism means I must learn to recognize my unfreedoms regarding racism.

Vociferously Reject Heresy

The greatest blasphemy of the whole ugly process [of slavery] was that the white man ended up making God his partner in the exploitation of the Negro. What greater heresy has religion known? Ethical Christianity vanished and the moral nerve of religion was atrophied. This terrible distortion sullied the essential nature of Christianity.

In 1554, Ignatius wrote an emphatic letter on heresy to Peter Canisius. He states that the success of heretics was due to negligence of those who should have taken action to prevent false teaching, particularly the clergy. He encouraged the publication of pamphlets and easy-to-use print materials to combat heresy. Centuries later, American Jesuits published thousands of pamphlets aimed at evangelization and defeating perceived theological enemies like communism. We rarely, however, took on the heresy of racism with the same zeal.

Racism is a faith. It is a form of idolatry…In its early modern beginnings, racism was a justificatory device. It did not emerge as a faith. It arose as an ideological justification for the constellations of political and economic power which were expressed in colonialism and slavery. But gradually the idea of the superior race was heightened and deepened in meaning and value so that it pointed beyond the historical structures of relation, in which it emerged, to human existence itself.

Racism became an American ideology and embedded in white Catholic faith. In recent years, we white Catholics have begun making strides to address this heresy. I wonder what would happen, though, if we Jesuits and all of our institutions were to give anti-racism the same or more attention than we give to other priorities. Doing so would fit perfectly within our guiding Universal Apostolic Preferences.

Discernment Leads to Action

But declarations against segregation, however sincere, are not enough. The church must take the lead in social reform. It must move out into the arena of life and do battle for the sanctity of religious commitments.

The fruit of discernment is action. Bad discernment leads to actions that simply confirm our attachments. For example, I regularly encounter people arguing against action on racial injustice by using quotes from Dr. King’s “I have a dream” speech. Like most historic figures, both Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Ignatius Loyola face the danger of softened, misused, and abused legacies. In their lifetimes, they demanded bold action.

The practical cost of change for the nation up to this point has been cheap. The limited reforms have been obtained at bargain rates.

Discernment demands concrete steps and actions. We Jesuits have begun making some important changes, such as researching our participation in slaveholding and being in dialogue with the descendents of individuals who were enslaved. Dr. King makes several suggestions that Jesuits, our institutions, and our colleagues could pursue: using our significant purchasing power to demand changes from businesses; clergy collaboration to demand racial and labor justice; and, most importantly, organizing.

Strong discernment and anti-racism are responses to God’s love and action in the world. They demand the magis, a full commitment to God’s liberating action. Pursuing this liberating action asks us to cast aside disordered attachments, seek truth and authentic teaching, and take bold action. Ignatian discernment and anti-racism ought to spur us to a transformation of ourselves and our communities.