Some days, you try and have a conversation and just feel like hitting your head against a wall. It goes nowhere, you feel frustrated, and you wonder why you bothered.

The last few days have been like that for me regarding immigration. A topic like this should be fairly straightforward to discuss. People are suffering, we have resources, let’s make things happen. And yet…

I have seen arguments like “I can call North Korea a shithole country, but it’s not racist, because South Korea is fine, they’re the same race, so calling something a shithole country is just saying something true.” (That one actually happened, by the way.) Arguments abound online about safety and security and how it’s their own fault that their country is so messed up. No matter how many times you try and talk, things just devolve into shouting.

Catholicism has a rich intellectual tradition that can speak to the current situation—a tradition which Pope Francis has brought out in full force, with his great pastoral instinct. Scripture has much to say about immigration. When Pope Francis declared in December that “the presence of God today is also called Rohingya,” referring to a massive group of Muslim refugees in Bangladesh, this was an absolutely Biblical argument based on Matthew 25.

But even for those who have questions about the Bible, there is a philosophical tradition that Catholicism draws upon.

One of the key concepts at our disposal if we wish to make an argument that does not rely on a specific religious tradition is that of human flourishing–the idea that there are drives and abilities that all humans have which it is good to fulfill. Human flourishing was the basis for much pre-Christian morality. Aristotle’s entire system of virtues revolved around what helps humans to flourish. Christians like Thomas Aquinas would later use this as the starting point for their own systems of ethics. When Jacques Maritain helped draft the U.N.’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, he was drawing upon this tradition of Aristotle and Aquinas. People have these rights because they need to flourish.

But as soon as we look at these rights, we start to see problems. Article 5, for instance, says that “No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” How many arguments have we seen since the start of the War on Terror about what counts as “torture,” or what is “degrading”? The statement seems so simple, and we should be able to say “respecting this right allows a person to flourish.” But we cannot even do that.

We cannot do that because we cannot agree on what it means for a human to flourish. And plenty of people don’t care if a person flourishes. Ron Swanson of Parks and Recreation called capitalism “God’s way of determining who is smart and who is poor.” That might be a caricature, but not by much. If you aren’t flourishing, this line of reasoning goes, that is your own fault. God helps those who help themselves, after all.

If we want to have the conversation on immigration, first we need to have the conversation on flourishing. We need to talk about what it means for a human to be what they were meant to be, and why that matters. Aristotle’s entire system of virtues, of how to live to develop our human potential—and many of the rights we hold dear today—depend on that conversation.

If we want to have the conversation on immigration, first we need to have the conversation on flourishing. We need to talk about what it means for a human to be what they were meant to be, and why that matters. Aristotle’s entire system of virtues, of how to live to develop our human potential—and many of the rights we hold dear today—depend on that conversation.

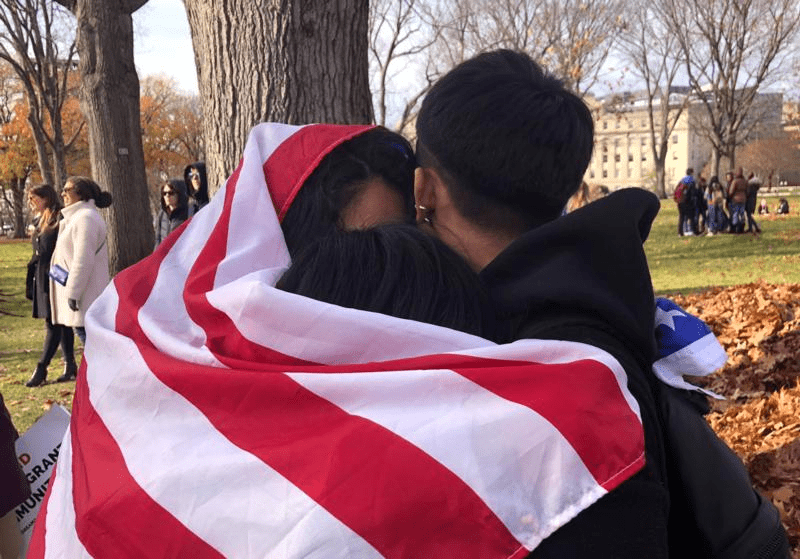

In the meantime, we can still continue to act and advocate. We can still point out the suffering of those migrating, we can point out how U.S. foreign policy is responsible for much of this suffering, and we can give aid and sanctuary to those who come. But while this might alleviate some of the symptoms for the moment, there is still an underlying disease of how we think about immigrants and their home countries that shapes how badly we treat them. Protests and aid are good, but they are short-term solutions.

The long-term solution is talking about what it means to be human, and what we owe to our fellow humans. We can help promote the people who have come here and help share their experiences of migration to help make the issue and its causes concrete for people. Earlier this month, for instance, the U.S. bishops’ conference sponsored an event at Catholic University of America that featured not only policy experts, but shared the stories of immigrants, including child migrants. It is easy to say “I don’t care” about an idea, but it is much harder to say “I don’t care” while you’re looking someone in the face.

These are the conversations that shape policy and move hearts and minds. Aristotle himself observed that if you are not getting anywhere at one level of conversation, you need to go to the more basic level until you have some principles you agree on. Right now, there is no shortage of disagreement. Our conversations are going to have to get very, very basic if progress is to be made.