I grew up around national parks and forests. My family didn’t have the money to take four kids to amusement parks, and so we instead learned the joy of camping and hiking. For the last decade or so, I have developed an incredible love of outdoor spaces not just for the beauty they offer, but the values they represent.

I have had several opportunities to live out these values as a volunteer/intern ranger at Wind Cave National Park and Newberry National Volcanic Monument, as well as other trail-building opportunities. As part of our ranger duties, we are entrusted with the safety of both the land and the guests who visit.

With recent debates about the value, use, placement, and size of public lands taking center stage, I’m curious: what makes public lands so important? What threatens our lands, and who does that threat most affect? How can we protect it?

In this first of three pieces, we’ll explore what makes public lands so great and why folks love them.

****

A few weeks ago, I spent a Wednesday evening gazing upon moonlit mountainsides and stars among dancing pine branches. This was after whitewater rafting and walking through wildflowers in snow-melting meadows. These experiences are all thanks to federal public lands.

In 2016, the US National park Service welcomed over 330 million visitors, an increase over 2015’s 307 million and 2014’s 300 million. Likewise, national forests saw a 5% increase from 2005 to 2015, not including over 300 million people driving through forest scenic byways. Public lands are booming in popularity. From their incredible vistas, to their deep views into the past, to a chance to determine our future, federally-managed public spaces help define and shape America.

Federal public lands offer a great deal of opportunities to the American (and international) populace. Each major branch of public land management has a different mission, but are largely unified in four main areas: protect history and heritage; support environmental stewardship; provide opportunities for recreation; and manage federal resources.

Public lands do a great deal to tell the stories of America. Lands, resources, and communities tell the stories ranging from pre-Independence, to the Civil War, ancient and modern indigenous communities, and jazz. Many of these stories belong to communities often otherwise ignored and oppressed, including the history of how setting aside and maintaining these lands often involves oppression. For many persons, these public spaces offer a locale to encounter their own heritage and identity.

For example, in a tour of Wind Cave National Park, you would learn about the Lakota creation stories associated with the cave, the first white men to come across it, and how it became a park. Even reading about the origin of national forests gives one a sense of the cultural, political, and ethical questions facing America – were lands for logging, leisure, or both? Ken Burns stunning documentary series “National Parks: America’s Best Idea” tells how America came to be and how those stories get passed on.

These lands also protect vulnerable environments. The land – and frequently water – found in these spaces tell of our environmental past, often holding keys to understanding our future. They help us to understand climate change, environmental degradation, the importance of forest and grassland fires, and much more. They provide places to not only protect endangered species, but opportunities for wildlife to flourish.

Endless opportunities for recreation like hiking, photography, camping, hunting, mountain biking, and sailing abound in federal lands. Even driving along scenic highways can count as a recreational visit to federal lands. Approximately 153 million people live within 50 miles of a national forest. And federal lands are not just western wanderings. They can be found in our biggest cities. When one considers places like the Smithsonian Museums and the National Mall, Statue of Liberty, and Golden Gate Bridge in highly populated areas, the number of Americans living near federal public spaces and opportunities for recreation are astounding.

In many ways, federal lands are democracy in action. They are the amalgamation of resources managed by the federal government for, well, us! They point to the limits of commodification, and instead create spaces that have value beyond just dollar signs. Wilderness areas, for example, are places so wild and free from human interference that trail crews can’t bring anything more advanced than a Pulaski. We also have a say – indeed a responsibility! – in the management of a massive array of resources like forests, burial grounds, dams, and artwork.

In addition to these values, public lands provide incredible amounts of employment, especially in rural communities. In Montana, for example, the outdoor recreation industry provides about 64,000 jobs. Though it may not seem like many, that’s one in every 16 jobs in Montana. Nationally, outdoor recreation provides over 7 million jobs. This recreation generates almost $125 billion in federal, state, and local revenue.

****

These spaces provide rich encounters with the environment, history, and joyful pastimes. For many, they also provide an encounter with God. For authors like Emerson and Thoreau, public lands represented the fullness of transcendentalism, a possibility to encounter the divine in the wilds of nature. John Muir, who grew famous for his dedication to protecting the Sierras, stated, “Wander here a whole summer, if you can. Thousands of God’s wild blessings will search you and soak you as if you were a sponge, and the big days will go by uncounted.” He later commented, “In God’s wildness lies the hope of the world – the great fresh unblighted, unredeemed wilderness. The galling harness of civilization drops off, and wounds heal ere we are aware.”

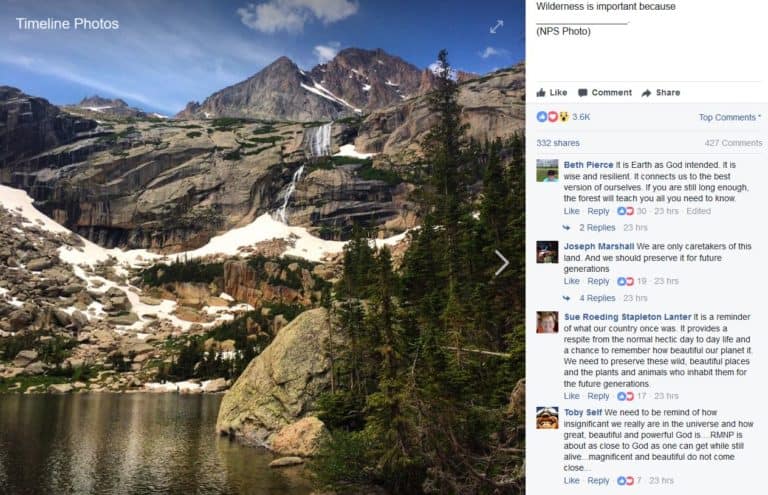

On a recent Facebook post from Rocky Mountain National Park, one gentlemen pointed out that the grandeur and beauty of the park were “about as close to God as one can get while still alive.” Another stated that the wilderness is “Earth as God intended,” a chance for us to be fully ourselves. One woman very eloquently said that, “[Wilderness] shows the glory of our Creator and it gives proper balance and health as He designed the earth to function! We need to be able to see The LORD manifested in His creation! Psalm 19 and Romans 1 and John 1,(The Bible).”

I recently surveyed my friends to see what made public lands so special to them. For many, public spaces are a place of reprieve. They’re a chance to relax, disconnect from technology. They’re therapeutic spots for deepening spirituality and restoring mental health. Public lands provide rich stories, often influencing our lives. For folks like my high school classmate Rob, these federal lands are “a quiet place to make sense of all our thoughts and knowledge and feelings, and hope to find wisdom and direction during our time there. And for some, it’s a way to connect with those close to us, or maybe not so close, and come closer in humanity as a whole. The scale and beauty of these places tend to lend perspective to those willing to drink it in…”

They’re the place of memories – hiking trips with dad or learning about the fight against slavery. Perhaps my friend and former coworker Marlene said it best: “My fondest memory was visiting Redwood National Park years ago with two young sons. Their faces were beaming with amazement as we walked through a grove of redwoods. It was not just a moment for me, it was a heartfelt ‘soulment.’”

****

What makes open spaces special for you? What are some of your favorite memories? What do you see as threats to these public lands? Let us know your thoughts in the comments and I’ll be sure to address them in the next piece.

Be sure to check back for the follow up pieces: the biggest threats to federal lands, and what we can do to get involved.