I loved La La Land.

Yet among other better-written and more powerful films like Manchester by the Sea, Hidden Figures, and Moonlight, I never for one thought it deserved to win the Academy Award for Best Picture this year. Still, I knew that La La Land was the overwhelming favorite1 going into tonight.

And – for a moment, what America expected came true. My heart dropped with disappointment as the La La Land cast walked up the stage. While I adored the nostalgic portrayal of Los Angeles, the romanticization of highway traffic, and the musical numbers that delighted my heart, the film couldn’t communicate the deep struggles people face because of race and sexual difference. It charmed my heart, but couldn’t pierce it.

My heart lay with Moonlight. That film documents the intersection of race, class, and sexuality in emergent Miami boy Chiron. Growing up with a single-parent, drug-addicted mother, Chiron realizes early on something is different about him. So do the other kids whose treatment of him lead him down a path he couldn’t have dreamed for himself. The movie reflects life, being at the same time painful and hopeful.

The film deserved to win best picture this year.

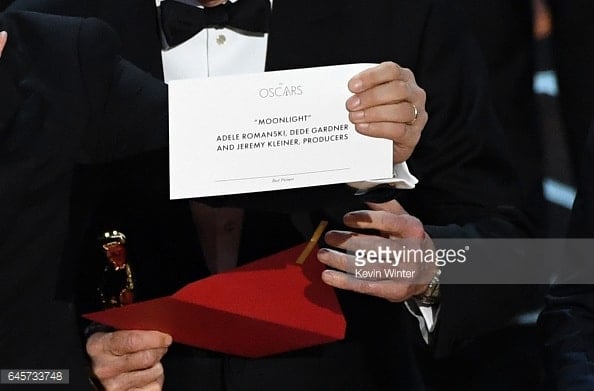

Regardless of your film preference, the next moment was literally horrifying. Some backstage producer2 emerges on stage. Was he really collecting Oscar awards from the La La Land group?

And in a frantic moment, Moonlight was declared the real Best Picture this year.

While it was good to see a movie more important to me win the big prize, it still hurt that Moonlight’s win was literally overshadowed by a controversy of someone else’s making. This seemed a cruel irony. A movie makes (beautifully) visible the struggle of someone who has been invisible to Hollywood and its moment in the sun is stolen.

* * *

Earlier in the evening, when accepting the award for Best Adapted Screenplay, Barry Jenkins said the film seeks to speak for “all you people who feel like there’s no mirror for you” especially during these troubled days in our democracy.

Tarell Alvin McCraney whose semi-autobiographical play3 became the screenplay stood with Jenkins and proclaimed the film to be for “all those black and brown boys and girls and nongender conforming who don’t see themselves, we’re trying to show you, you, and us.”

And so, in Faye Dunaway’s Steve Harvey moment,4 the story of someone who is already nearly invisible — a black boy growing up poor trying his best to make sense of his emergent sexuality — was made less visible still. And this is a story that needs telling: how our demonizing of some traumatizes and stunts the humanity of others.

But, more importantly, Chiron’s story needs telling because it is a story of hope. It calls us to imagine that there is another world possible — one where we can break out of those early traumas to find redemption and healing. One where people can break out of categories aimed to limit, constrict, and marginalize.

That message is fragile and elusive. When we lose our focus on those whose lives are marginalized in any way, they disappear. It is so easy to allow our own insecurities, prejudices, and selfishness to propel us into ignoring people who we don’t understand. And we can lose sight of the humanity in people who we do not see. I hope this doesn’t get lost in the mix up.

- One site had it at near even odds. ↩

-

Watching the #Oscars producers slowly tell the #LaLaLand team they didn’t win Best Picture is WILD. Keep your eyes on the background pic.twitter.com/3TRUWZAMjH

— Jarett Wieselman (@JarettSays) February 27, 2017

- See the excellent NBC story here. ↩

- ↩