Consensus is a difficult thing, we’re told, all but impossible to come by as our political climate continues to warm. Republican initiatives are threatened with veto and presidential proposals promise to be met with filibuster or, if necessary, government shutdown. Members of Congress do or don’t toe the party line and gridlock is a seemingly inevitable result.

So when Congress passed the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) on December 10th of last year to overwhelming majorities (85-12 in the Senate, 359-64 in the House) many excitedly jumped in to express their approval of the bill. “This is a Christmas miracle,” President Obama exclaimed. “A bipartisan bill-signing right here!”

Conservatives lauded ESSA for transferring power from D.C. to the states. Local responsibility for holding schools accountable became their watchword. “Fed ctrl [sic] rarely goes in reverse but it just did,” American Enterprise Institute scholar Rick Hess tweeted.

Progressives were enthused by other elements of the bill. “ESSA allows states and districts to take a more holistic approach to measuring progress by using additional measures of school and student success beyond test scores,” the Center for American Progress opined.

The unanimity was a welcome respite from the norm. The ESSA is so lauded, in fact, that when I googled “Every Student Succeeds Act reception” I had to scroll to the 3rd page before I found anything resembling criticism. This bill seems like a win for everyone.

For some, ESSA is a win simply by not being its predecessor – the much-maligned No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB). Once a supporter of NCLB, former Assistant Secretary of Education Diane Ravitch argues that its overemphasis on test results ended up having strongly negative consequences. “The basic strategy is measuring and punishing,” she said, “and it turns out as a result of putting so much emphasis on the test scores, there’s a lot of cheating going on. Instead of raising standards it’s actually lowered standards because many states have ‘dumbed down’ their tests or changed the scoring of their tests to say that more kids are passing than actually are.”

Others, like President Obama’s former Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, laud ESSA because they think it offers the right corrections to succeed where NCLB failed: “Although well-intended, the No Child Left Behind Act… has long been broken. We can no longer afford that law’s one-size-fits-all approach, uneven standards, and low expectations for our educational system.”

Bipartisanship. Empowering states and local districts to succeed where national government has failed. Emphasis on accountability. And most importantly, concern for failing students and schools. Sounds amazing.

Actually, it sounds a lot like No Child Left Behind.

* * *

Before we join the chorus of voices praising ESSA as “the fix” to the many problems facing U.S. public education, we would do well to remember that NCLB was also universally praised when it was passed in 2001. It sailed through the Senate (91-8) and the House (384-45). Conservatives lauded the introduction of accountability to the education sector, and progressives were excited that the nation’s most struggling students and students would receive the attention and funding that they deserved.

Fifteen years later, most experts agree that NCLB has failed our children. Will we be saying the same thing about ESSA in 2030? Any real shot an answer begins by getting the facts down first. Comparison like this one help us evaluate the two bills across four key areas: accountability, assessments, standards, and teacher/leader effectiveness. Even though such comparisons only offer us an incomplete picture of what a good school looks like, they are still crucial for bringing the policy differences between ESSA and NCLB to light. When I took a look at these comparisons I found three major differences between the bills.

The first keys on whether federal or local education policies are in control. ESSA allows states/districts to create their own standards and assessments, provided they have a system in place to judge their effectiveness. One of the key criticisms of NCLB, from both sides of the aisle, is that it was too prescriptive. For example, its mandate that 100% of students would be proficient in reading and writing was simply unrealistic. By doing away with such requirements, ESSA clearly seeks to limit the control of the Department of Education of what particular schools and districts must do to comply.

A second, related, difference is that ESSA abandons NCLB’s insistence on treating all students exactly the same. Instead, certain groups (e.g. English language learners and students with disabilities) can be evaluated on different scales. And thirdly, ESSA seeks to restore some elements of a well-rounded education that were deemphasized by NCLB. By defining math and science as “core” academic subjects and grading schools based these areas, NCLB sent a clear message to schools: reading and math are primary, and everything else is secondary. This lead many schools to drop their programs in the arts, physical education, and other “non-core” subjects.

Clearly, NCLB did not meet its goals: the same schools continually placed in the bottom five percent, and the same students continued to fall behind in reading and math. In other words, many of our students were left behind. So, no wonder many are hopeful that the changes instituted by ESSA show signs of being impactful. It’s great that power is being placed lower on the scale, being put in the hands of principals and teachers rather than politicians.

But there’s one way in which No Child Left Behind and the Every Student Succeeds Act are very much alike. And it’s a similarity that we don’t like to talk about — something that affable Republicans and celebratory Democrats and laudatory media have all agreed to ignore: school integration.

NCLB and ESSA are sadly alike in their refusal take any steps toward integrating our schools either by race or socioeconomic status.

* * *

It was in 1966 1 that sociologist James Coleman discovered the one factor that affects student achievement far more than any other: the socioeconomic composition of the student body as a whole. For all the ink spilled about student-to-teacher ratios, AP class offerings, and teacher quality, these factors are far less effective at reducing the achievement gap than one simple word: integration.

We might think that things have changed since 1966, but they haven’t. Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam recently found that Coleman’s discovery still holds today. In his latest book, Our Kids, Putnam quotes Stanford sociologist Sean Reardon, who writes that the “gaps in cognitive achievement that we observe at age eighteen are mostly present at age six. School — unequal as it is in America — plays only a minor role in alleviating test score gaps.”2

We might think that things have changed since 1966, but they haven’t. Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam recently found that Coleman’s discovery still holds today. In his latest book, Our Kids, Putnam quotes Stanford sociologist Sean Reardon, who writes that the “gaps in cognitive achievement that we observe at age eighteen are mostly present at age six. School — unequal as it is in America — plays only a minor role in alleviating test score gaps.”2

Schools aren’t the source of the “achievement gap” in this country. Segregation is.

It’s an American — maybe a human — truism that we gravitate toward the people that resemble us. Our neighbors are likely to have similar median incomes and educational status. Crucially, they are also likely to be the same race.

So it’s no surprise that our schools mirror these communities. If our parents are highly educated (bachelor’s degree or higher) and white, they will send us to a school where our classmates also come from highly educated, white families. The result? An environment where all voices (teachers, administrators, parents, classmates) unite behind a common purpose: getting every student to college so she can be successful.

But if that example sounds familiar, let’s imagine another one, one where next to no one in the class has parents that have gone to college. Where most families are below the poverty line. Where – and it hurts here to put in words what the data says is true – all your classmates are much more likely to be black or Latino than they are to be white.

I can’t help feeling that the changes that the ESSA is putting into place, though praiseworthy, are not enough. Whether we ignore or it or not, economic and racial integration matter much for a school’s students than how many AP classes are offered or whether the Common Core is in place. Despite our reluctance to talk about it, apart from a few exceptional cases, students in these disintegrated environments are not going to go to college. Which means they are unlikely to have any social mobility. Which means they are stuck. And all this before kindergarten begins.

NCLB and the ESSA are each massive bills that have been meticulously crafted to satisfy Republicans and Democrats alike. Even more, they reflect most of the best educational thinking of their time. But both of these bills miss the key point: if we are really serious about closing the achievement gap, we must push for racial and socioeconomic integration in our schools. Until we do, we cannot expect anything to change.

For all the talk about the problems in our divided America when it comes to our education system, it’s what we’re united in ignoring that presents the real problem. It’s no party puncturing the celebratory balloon, but our near unanimous passage of bills like the ESSA and NCLB should in fact be unsettling. They should make us question why it is that we’re all in agreement. Is it because agreement is easier?

The pointed fact is that, in this instance, our unanimity is founded not only in agreement but in a collective silence. George Carlin had his “seven dirty words.” U.S. public policy has its own: race and class.

* * *

Segregation in this country has always played itself out in our schools. In 1954, Brown v. Board of Education had to explicitly state that separate was not equal.

But, contrary to some contemporary narratives, segregation did not end with Brown. When Arkansas’ Little Rock Central High School admitted nine African-American students in 1957, the reaction was so violent that President Eisenhower had to send in the National Guard to protect these students. Almost a decade later, in United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, the Fifth Circuit Court needed to order school districts to racially balance their schools under federal guidelines.

While the South’s segregation was violent and explicit, other parts of the country have been more subtle. In 1976, 45.1% of the South’s African-American students were attending majority white schools, compared to 27.5% in the Northeast and 29.7% in the Midwest. “Yes, but that was a long time ago,” I like to whisper to myself, “today things are much more equitable.” But it’s not the case. We Americans continue to resist socioeconomic and racial integration in our schools.

Look, for example, at what happened when integration was forced upon the high performing school district of Francis Howell in Missouri. When the nation’s lowest performing school district (Normandy) lost its accreditation, a transfer law was triggered that allowed Normandy students to choose a nearby district. An excellent episode of NPR’s This American Life called “The Problem We All Live With” tracked what happened, but you already know the story; it’s a tale as old as America. Families in Normandy, almost all African-American, were elated at the opportunity to get their children out of failing schools and into the much better schools down the road. Many Francis Howell families, almost of them white, fought this integration tooth and nail.

This integration took place in August 2013. No, President Obama didn’t need to bring in the national guard, but it ought to make us ask how much have we really progressed since 1957.

* * *

Let’s be clear, though: this is not just a Missouri problem. Or a southern one. It is an American problem. It is America that continues to disintegrate, to stratify itself by income and race. And our disintegrated schools are the result of our refusal to live well with one another.

Moreover – and as a Jesuit and a Catholic this is an even more urgent confession – this is not just a public, or a public education problem. Jesuit schools, private schools, Catholic schools – the schools that we hold dear have a serious integration problem as well.

“What about the Cristo Rey model?” we might ask. “Isn’t that all about bringing Catholic education to those who can’t afford it?” On one hand, yes, it is. However, Cristo Rey schools are themselves not well integrated along racial or socioeconomic lines. Most Cristo Rey schools have Latino and/or African American students, but very few white students. All of the students are economically poor. I don’t mention this to throw stones at the Cristo Rey model (which I love, and wrote about here). Instead, I mention to highlight how difficult it is for even the most successful and laudatory school models to take on a problem we don’t want to talk about.

Public or private, independent or Jesuit, we need to start talking about racial and socioeconomic integration in our schools. Otherwise we are ignoring the primary source of the achievement gap and become complicit in preserving an unacceptable status quo.

This starts by being skeptical when we hear voices proclaiming the ESSA a panacea for our kids. Yes, it is a better law than NCLB, but that doesn’t mean it’s going to solve the problem we’ve long ignored. Which means we should be unsurprised when, ten years from now, the results from the Every Student Succeeds Act are more or less the same as those produced by No Child Left Behind. If Congress really wants to get serious about closing the achievement gap, they will begin by looking at racial and socioeconomic integration in our schools.

Furthermore, let’s not be content to let this be a problem for Congress to solve. Let’s push for racial and socioeconomic integration in our own schools, no matter whether they are public or private, non-sectarian or Jesuit.

–//–

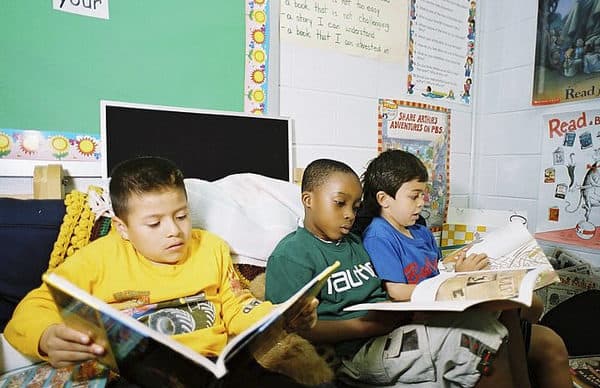

Title image courtesy of US Department of Education, available on Flickr here.

Chairs on desks image, “A classroom at Villa-Maria high” by Flickr user Colleen is available here.