My friends are not normal. Yes, they are (in my obviously biased opinion) extraordinary people, but what I really mean is that they are not at all representative of humanity. The problem comes when I think that the issues we talk about are other people’s primary concerns. They aren’t.

My college friends are impressive in their accomplishments and dizzying in their mobility. Of the twenty of us who stay in touch with an ongoing WhatsApp conversation, exactly three currently live in the state where they grew up. Three. And most of us have lived in at least three different states or countries since we graduated.

Because jobs and degrees frequently take people I know away from those that they love, I assumed it was an experience most people could relate to. I was even planning to write an article about it.

And then Arthur C. Brooks’ recent New York Times column overturned my assumptions. Looking at census data, he notes that Americans are less likely to move now than at any point since 1948. He adds:

In the mid-1960s, about 20 percent of the population moved in any given year, according to the United States Census Bureau. By 1990, it was approaching 15 percent. Today it’s closer to 10 percent. The percentage that moves between states has fallen by nearly half since the early 1990s.

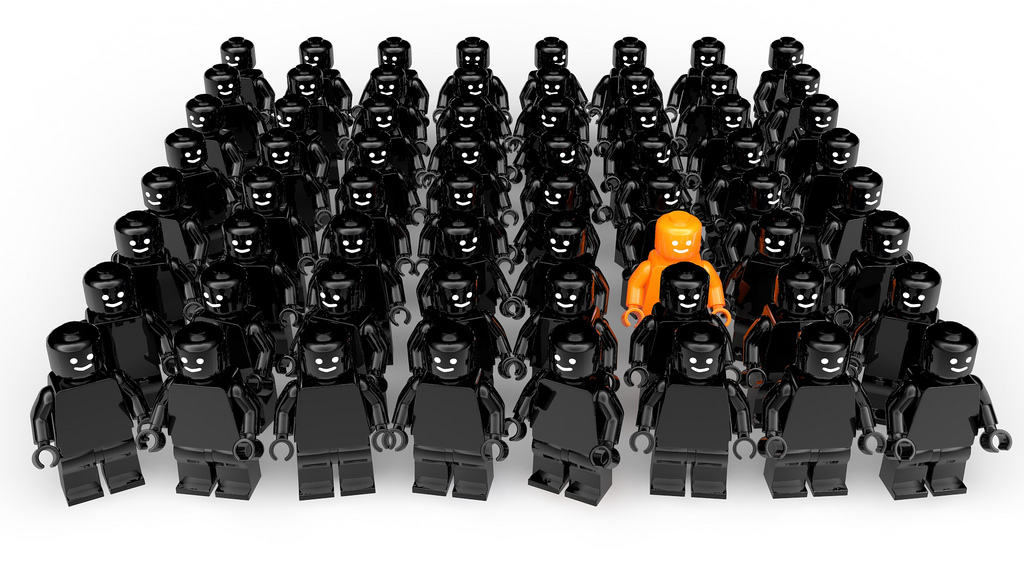

The gap between my perception of reality based on my close friends and reality, backed up by actual statistics, indicates how I need to break out of my little bubble. I might know a thing or two about people who are a lot like me, but it is foolish to think that what is normal for me is the norm.

A recent Atlantic article by Derek Thompson indicates how I’m not alone in making inaccurate assumptions.

In “The Average 29-Year-Old,” Thompson writes that “millennial” is oftentimes used as a media shorthand for “a college-educated young person living in a city” — a description that fits pretty much all of my friends. Most young adults in the US, however, did not graduate from college and do not live in cities. He writes:

The average 29-year-old did not graduate from a four-year university, but she did start college; held several jobs, including more than two in the last three years; is not as likely to be married as her parents at this age, but is still likely to be living with somebody; is less likely to own a home than 15 years ago, but despite the story of urban renewal, is more likely to live outside of a dense urban area like Brooklyn or Washington, D.C.

There’s even a term, “majority illusion,” to describe the inaccurate assumptions that people like me make based on one’s social circle.1

So, what is to be done?

Interestingly enough, the same column by Arthur Brooks that helped me see some of my own inaccurate assumptions is probably an example of what not to do.

Brooks frames his discussion of changes in Americans’ likelihood to move in terms of an “immobility problem,” but many people do not consider staying close to family and friends to be a problem. He writes that “migration has long been seen as a key to self-improvement” but does not discuss the negative effects it can have on community or family bonds. His column – which even suggests that unemployed residents of Mississippi should pack up and move to New Hampshire! – does not actually quote anyone from the places where he describes people as “stuck.”

Another Times columnist, who coincidentally shares the last name Brooks, offers another way. In a refreshingly humble mea culpa in which he looks back on how he was wrong about the rise of Donald Trump, David Brooks writes:

I was surprised by Trump’s success because I’ve slipped into a bad pattern, spending large chunks of my life in the bourgeois strata — in professional circles with people with similar status and demographics to my own. It takes an act of will to rip yourself out of that and go where you feel least comfortable. But this column is going to try to do that over the next months and years.

David Brooks recognizes that there is a problem, and I am interested in how he will expose himself and his readers to different perspectives in his columns in the years ahead. I hope to learn from his example — and from the people he learns from.

Not drawing conclusions based on one’s limited social circle is really just an elaborate way of reaffirming what many of us learned as kids: that when we assume, it makes an ass out of u and me.

– // –

The cover image from Flickr user Village9991 can be found here.

- In addition to such illusions influenced by my social circle, there is surely a whole lot of white, male, American privilege that warps my view of reality. ↩