The GOP Establishment doesn’t want Donald Trump to be the nominee. But is there anything they can do about it? And what happens to the Republican party?

[Editor’s Note: This is part II of Bill McCormick’s extended look at the GOP’s options. Part I was published on Thurs. March 9.]

Parties Come and Go

With the next round of primaries occurring tomorrow, on the Ides of March, it’s an auspicious time to continue to take stock of national politics.

Let’s say that Trump does win 1237 delegates by the summer, or he survives a brokered convention. What then?

Well, either he wins or he loses the general election. No doubt either path would be full of surprises. He could win by energizing the GOP base, which would likely involve stoking white populism and anti-Clinton sentiments. Even if he wins, of course, he may succeed in alienating a substantial portion of the GOP base.

He could lose, however, by depressing GOP turn-out and mobilizing Democrats against himself. If he loses that way, it could be in a big way.

If so, then the GOP will have the opportunity to do the hard thinking that they seem not to have done during the past seven years. Perhaps a Trump candidacy would be bad for candidates down the ticket, as well, resulting in losses in the House and Senate. The GOP could fall out of power for some time. This would not be without precedent.

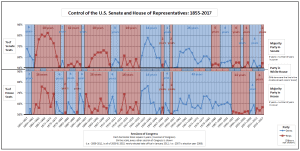

In fact, for most of the history of this country, our two political parties have alternated control over the White House and Congress, typically for some decades at a time. As one party gains ascendancy, the other recedes into the the minority. (Although there are important exceptions, like Eisenhower winning two terms in a Democrat-dominated era.) Note such regular intervals of partisan control in this chart:

[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Presidents_and_control_of_Congress]

[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Presidents_and_control_of_Congress]

Recent decades, however, have blurred this pattern. Moreover, rare have been the moments since 1968 when the same party has held both the Congress and the White House. Given the overall historical trend of U.S. politics, can we expect this instability to settle down into relatively stable alternations of power? If the Trump nomination leads to a GOP bust, then we might expect the instability to settle.

If the GOP loses this election, then the party could splinter or even disintegrate. But these are unlikely scenarios. The two-party system has been remarkably resilient over time, and nothing predicts success like success. Third parties and independent runs have not met with much success, as Michael Bloomberg has had to admit.

So perhaps the GOP is here to stay. But if parties do not die, it is because they change. Periodic massive changes are what political scientists have called “re-alignments.” Indeed, the Democrats and Republicans have both re-invented themselves in recent memory. The FDR coalition that allowed the Democrats to control Washington for decades broke up on the shoals of civil rights and Vietnam. Indeed, the Democrats endured some dark days, perhaps only finally ended when Bill Clinton took office in 1993 with his centrist coalition.

For their part, the Republicans were reborn with the Southern Strategy of Goldwater, Nixon and Reagan, a strategy that deliberately sought to nab white Southerners who felt abandoned by LBJ and Carter. It thus has come to pass that the party of Lincoln now attracts conservative white voters, and that black and liberal white voters feel most at home in the former party of George Wallace and Harry Byrd. You can’t make this stuff up.

For many, it is is a sign of psychological pathology that so many in the chattering class are devoting time and energy to envisioning scenarios by which Trump could still lose. That may be. People often only ask questions when bad things happen, as Mark Wahlberg says in the movie “I Heart Huckabees.”

But Trump’s rise, we have seen, raises a host of fascinating questions about how the primary system works, how parties function, and how they must change when they do not. My hope is that all of this wailing and gnashing of teeth would take a contemplative turn — that we complain less and reflect more. For how else will we look beyond our present morass to the future?

Humility?

What could a Republican party of the future look like? That is something to be worked out in the next decade. As David Brooks has argued, this task makes this nomination particularly important:

This isn’t about winning the presidency in 2016 anymore. This is about something much bigger. Every 50 or 60 years, parties undergo a transformation. The G.O.P. is undergoing one right now. What happens this year will set the party’s trajectory for decades.

Words like “transformation” conjure the image of a beautiful butterfly emerging from a cocoon. But it is the humble caterpillar that must enter the cocoon, and remain for some time. Perhaps life in the cocoon, willed or not, is the GOP’s immediate future.

This is a fate that would require humility, a virtue in short supply in our political life. It is not, moreover, only the GOP who are bereft of it. I suspect where we most need humility is in our desires for a Great Leader, someone who can sweep in and make everything better. U.S. politics has come to revolve around the presidency to an obsessive level. Eight years ago, it was Barack Obama who was going to fix everything. Now it’s Donald Trump. Who will it be next in 8 years?

This is a profound irony: many of the same people who criticized Democrats for idolatry toward Obama are now making a graven image of Trump. Thus is the cycle of unreasonable expectations and crushed hopes perpetuated. The worst part about such “presidentialism” is that it encourages the perception that voters have no control over the process, increasing feelings of both powerlessness and frustration. Then, when the worst does come to pass, one must choose between being one of the two dominant postures towards American politics: angry and apathetic.

The first step out of this cycle of anger and apathy is to moderate our expectations for the presidency, even for politics in general. To do so would restore a sense that citizens, too, have a role to play, that we cannot simply drop our problems at the feet of the Great Leader and say, “here, YOU fix it.” Then we would be confronted by the question of what we should do with this new-found responsibility. What responsibilities do I have as a citizen to the good of my country? What part ought I contribute to this enterprise? I suspect the answer, if we’re honest, is more than “my anger and apathy.”

–//–

Title Image: “Fighting Elephants” by Flickr user shplendid is available online here.