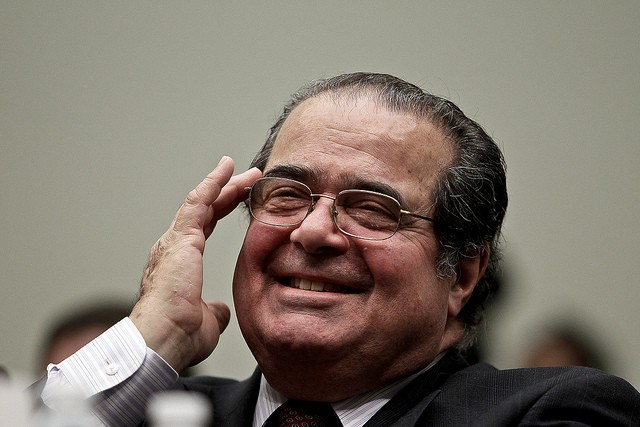

I met the late Antonin Scalia only once in my life. The college seminar I took on the Supreme Court included a trip to Washington, DC, during which we observed oral arguments and, afterwards, Justice Scalia spoke with us for the better part of an hour. It was incredibly generous, meeting with students for no reason other than he wanted to help us in our education, answering our questions, and offering us insights. He was gregarious, witty, passionate, and willing to engage us for the sake of our education.

It was a great moment for us, though likely less so for him. Indeed, I imagine he had done that routine countless times during his tenure as a judge and professor. He would not have known me. I, though, certainly knew him.

Indeed, going to law school in the first decade of the twenty-first century, it was impossible not to. His opinions were among the backbone of contemporary constitutional law. They were full of memorable quotes (“argle-bargle” being a recent and particularly bizarre one.) Moreover, they were passionate; you never had to ask what this Justice thought about a case. In many ways, he defined the mainstream of contemporary conservative legal jurisprudence.

To be sure, I rarely agreed with him. Indeed, my personal judicial hero was the other great Catholic of the Supreme Court, William J. Brennan, Jr, Scalia’s polar opposite when it came to jurisprudence.1 If his judicial philosophy seemed stuck in time, this is because he remained dedicated to the “dead” constitution.2 While this led Justice Scalia to be an energetic (if surprising) supporter of the rights of criminal defendants on certain questions and to declare flag burning to be protected speech, it also led him to be a staunch opponent of gay rights, of abortion, and much of the modern regulatory state. Through it all though, Scalia was often lauded for his writing, witty and memorable.

Yet it is precisely that writing, not merely disagreement with the man’s philosophy, that trips me up. For as witty and intriguing as it is, ultimately, it was equally problematic. Argle-bargles aside, Scalia’s writing had the tendency to become overblown, alarmist, and even rude. Particularly in dissent, what made his opinions memorable was language unexpected for a justice. For example, he described Justice Kennedy’s opinion for the Court in last summer’s gay marriage case as “the mystical aphorisms of the fortune cookie.” Or, in his concurrence/dissent in the abortion case of Planned Parenthood v. Casey3, Scalia is sidetracked from a strong and insightful critique of the lead opinion’s serious flaws and problems to a diatribe against “The Imperial Judiciary” that casts the justices he disagrees with as Nietzschean mystics leading the Volk into a new enlightenment. In another case, he casts the majority’s concerns about public school students students being forced to sit silently at a prayer before a football game, despite their disquiet at being perceived as supporting a prayer they disbelieve in, to be “nothing short of ludicrous.” And, when Justice Stephen Breyer last summer raised serious concerns about the death penalty, Scalia dismissed them as not only internally contradictory (a legitimate critique) but as “gobbledy-gook” (not a legitimate critique). Agreement or disagreement with Scalia’s positions is not the point. We can agree with him on the merits but still be frustrated with the rhetoric, the tone, and the style.

Often, I think, Justice Scalia’s passion was the source of such language. And this passion was genuinely a good thing. Indeed, when it did not slide into ad hominem or alarmism, his style was incredibly effective. Writing in Slate, Yury Kapgan highlights many of his compelling linguistic quirks. Scalia could “create truth out of metaphor” he writes, a powerful talent when the written word is essential to your vocation. Yet, as Dean Erwin Cherminksy notes, Scalia’s tone does “set[] a terrible example for young lawyers” and law students. And, I’d add, for the general public. It coarsens our discourse and moves us away from useful and necessary discussion about important, intransigent, and difficult policy and legal disputes. Instead, we are scoring cheap points. That might be nice for late night, but it is a shame for the United States Reports.

Antonin Scalia was an incredibly important judge, a justice of deep faith and passion for his vocation. His life had and will continue to have consequences for our lives for years to come. He helped make the language of the law accessible, interesting, and fascinating. At the same time, he also helped make it one more arena to score a cheap point from those we disagree with. No man, though, is perfect. Perhaps the best memorial is to pray for light perpetual upon Antonin as he rests in the next life, but to withdraw such light from those decisions which ridicule litigants and judges and coarsen our discourse

*******

Cover Image Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia by Flickr User Stephen Masker, via Flickr Creative Commons, available here.

- Indeed, their dueling opinions in the matter of Michael H. v. Gerald D., 491 U.S. 110 (1988), remain one of the great primers on the differences between conservative and liberal approaches to questions of personal freedom. ↩

- Which might also explain why the justice was apparently the world’s only St. Thomas More cosplayer. ↩

- Casey’s judgment is incredibly mixed, confusing, and one of the most difficult to sort out, regardless of whether one agrees with it on the merits; the lead opinion was a “joint” opinion by three justices, and nearly every other justice wrote a separate opinion concurring in some parts of the lead opinion and dissenting from others. ↩