Have we Jesuits educated you for justice? You and I know what many of your Jesuit teachers will answer to that question. They will answer, in all sincerity and humility: No, we have not. If the terms “justice” and “education for justice” carry all the depth of meaning which the Church gives them today, we have not educated you for justice.

In 1973, Jesuit Superior General Pedro Arrupe delivered his famous “Men for Others” speech to a group of Jesuit alumni in Spain.1 This seminal talk prompted Jesuit schools around the world to examine their work and their mission. Arrupe was disheartened that millions of Jesuit-educated alumni around the world had not learned to love the poor, to live a faith in service of justice.

I have been in and around Jesuit schools my entire life, and this year I have begun teaching at a Jesuit high school – as a Jesuit. I have my own answer to the question of whether the Jesuits have educated me for justice. But what about what I have done for my students? Forty-two years after Arrupe’s speech, I decided to ask them.

***

I teach theology to first- and third-year students at Marquette University High School in Milwaukee, WI. My junior course, Christian Discipleship, presents the theology behind Catholic Social Teaching, which is designed to help students think about how to live out that teaching.

The first homework assignment I gave them was to read Fr. Pedro Arrupe’s famous speech, “Men for Others.” As a teacher, I wondered how I could get them to engage more deeply, and personally, with the text. As I reread the speech, I came across Arrupe’s question: “Have we Jesuits educated you for justice?” I assigned the students to write two paragraphs answering that question, and a third paragraph asking them what injustice they find particularly challenging, distressing, or confusing.

I expected a collective general nod of agreement, and perhaps an occasional “yeah, but we could do better.” Instead, I received in-depth analyses of the injustices they see and experience in high school – and a clear desire to learn more, particularly about the injustices they found confusing.

So I gave them the question: “Have we Jesuits educated you for justice?” Their responses can be broken down into four broad categories:

1) yes, because that’s what the teacher wants to hear…

2) yes, and here are the ways I’m challenged…

3) no, I have hardly been educated for justice.

Lastly there were the students who – in a way that would make Socrates proud – asked questions about the initial question, and then supplied their response.

***

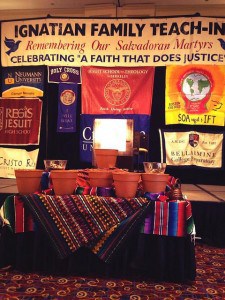

Several of these young men answered (1) yes, mostly likely because they thought I would reward their answer. Other students answered (2) yes, and spoke movingly of their experiences. Marquette High has a yearly school-wide theme. Last year’s theme was “Work for Justice.” The school community reflected on and commemorated the 25th anniversary of the El Salvadoran martyrs. Additionally, the school read Enrique’s Journey and had frequent discussions about the plight of immigrants in the United States.

The 2) yes students found the school theme and book to be positive, transformational experiences. Moreover, they felt empowered to have more discussions and seek new answers. One student, “Frank,” answered, “I am confident that Marquette University High School has given us the tools we need to go out and work for justice.”

They also related questions of justice to their experiences at Marquette High and the surrounding community. Frank hopes that “students, faculty, and administration will go out and set the world on fire throughout their daily life.” His own education inspires him to aid others in getting a similar education. The hope is to help them fight poverty, thereby defeating injustices like famine and war.

I had a few students that said, 3) “No, I haven’t been educated for justice.” These were blunt answers that did not skirt any hard questions. These students felt like their theology classes might bring up questions of justice occasionally, but their experience as a whole left them empty.

One of my students, “Tim,” said that the school had made a good start in educating for justice, but still needed to take greater action. Despite last year’s theme of “Work for Justice,” Tim feels that little has changed in the school. In particular, he sees the need for justice to become a normal part of who we are as school, rather than a remarkable ‘extra’. He explains:

The term “radical” has such a negative connotation that people are afraid to do the right thing in fear of being deemed as such. In order for justice to be taught, the “idea” of being a radical needs to be normalized. Jesus was a radical, and definitely an advocate for true justice. So why is it so taboo to ask for justice?”

The 3) ‘no’ students said that for the majority of their school day, and in their homework and extracurriculars, they had been taught to think about one thing: success. “George,” for example, felt that “a majority of the teaching done by Jesuits and MUHS staff has been focused more towards the preparation for college and education” rather than forming religious and justice-minded men.

Sadly, they saw justice (sometimes like theology classes) treated as a secondary venture, to be talked about occasionally, but pushed to the side for subjects like math and science. These students felt the school wanted them to stand out more for their educational prowess, not their Catholic commitment. I must admit to being pleased to see several students who wanted to challenge their comfortable setting. They wanted to see questions of justice brought up in every class and outside the bounds of classroom walls.

The final group of students did more than I had hoped. They didn’t just answer, but analyzed the question. Most students in this category believed their Jesuit education helped them consider and ask questions about justice. But they want more.

One student, “David,” made a remarkably astute observation. The Jesuits had not educated him for justice. Rather, the Jesuits had educated him about justice. One little preposition, and the whole phrase takes on a different meaning. David explains that Jesuit education has done an excellent job of educating about justice. Educated for justice is another question, though. He responds,

“During my journey at Marquette University High School, I believe that my Jesuit education has yet to fully educate and prepare me to work for justice. During classes and assemblies I learn about only the ideal processes and outcomes necessary to create economic, political, and social justice even though I have not learned about the reality of the progressions and results.”

David knows that we are called to live justly. He understands what a just society should look like and how it should behave. He says, correctly, that this was not the ultimate goal of Arrupe. Rather, Arrupe wanted Jesuits to educate for justice. Although thankful for his education, he feels limited, powerless, and lacking the tools necessary to make change in the world.

***

The excellent response forced me to pause and consider my own nine years of Jesuit education. Did St. Louis University High, Creighton University, and Fordham University educate me for justice? Have my five years of being a Jesuit educated me for justice?

Honestly, the questions makes me uncomfortable because it leaves me uncertain about my own experience and identity. I want to answer a full-hearted “Yes!” because of the teachers and mentors that helped shape me. But a nagging part of me mutters “not really,” because of the work we still have ahead. As a Jesuit, I want to say that in the forty years since Arrupe, we have learned to educate for justice. But the truth is, we have a long way to go.

My hope is that as an educator and part of wider institutions, we can move from educating about justice toward educating for justice. I hope we can use tools of social analysis to challenge our comfort. I hope we can emulate Pope Francis by taking in refugees, working for economic justice, and taking action to protect the earth. I hope we can follow the challenging words of Arrupe: to truly shape our students to be men and women for others.

So, Jesuit-educated students, alumni, and friends, I ask you: Have the Jesuits educated you for justice? How can we do more? How can we never tire of living a faith that does justice?

- Arrupe’s speech was so-titled because nearly all of the Jesuit alumni in Europe were male. The vision Arrupe sets forth is not particular to the sex of Jesuit students, however. This explains why coeducational institutions, particularly in the United States, have adapted this phrase as “Men and Women for Others” or “People for Others.” Later tweaks, emphasizing solidarity over service, have yielded “Men and Women for and with Others.” ↩