A thinly veiled piece of climate alarmist propaganda. A groundbreaking exposition of Catholic ecological thinking. Well intentioned but economically naïve. A slippery slope towards extremist environmentalist positions.

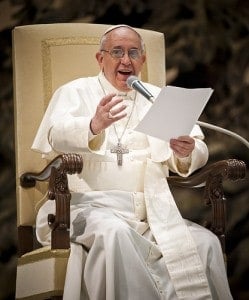

Such are the reactions to Pope Francis’s ecology encyclical — and it hasn’t even been published yet. Nevertheless Vatican sources have confirmed that the encyclical will appear sometime this month. It is reported that it will bear the title “Laudato Si” (Praised Be), a quotation from a St. Francis’s prayer praising God for creation.

The media storm created in the run-up to the forthcoming document is both unparalleled and exciting. The optimist in me hopes that the encyclical will demonstrate the way the Church is responding to a critical “sign of the times” confronting our age. I hope it is yet another opportunity to champion the rights of today’s poor, with an eye towards the well-being of future generations as well. But, I also have a nagging suspicion that the encyclical’s detractors may blunt the evangelical potential of a document showcasing Catholic theology of creation stewardship. The mainstream media have given platform to critical voices. With characteristic hyperbolic aplomb, a Fox News report has claimed that if Francis goes through with the encyclical, he “will be aligning himself with some Church enemies … which will test the faith of some Catholics.”

So we have a task on our hands. Building on the legacy of Popes St. John Paul II and Benedict XVI, the encyclical will further provide a footing and a framework for Catholic environmental initiatives. But when it is (finally) published, we need to be equipped to answer the critics. More importantly, we must be in a position to frame the debate on common ground, and emphasize the positive elements of this encyclical. How can we do this?

Here are six suggestions for the task:

1. Remember it’s not only about climate change.

Now the encyclical is almost certainly going to deal with the moral obligations of responding to the challenges of climate change in terms of prevention and mitigation. But it will put climate change in the context of the bigger picture of the increasing disconnect between humans and their natural environment. We often speak of humans having “dominion” over the earth. Some frame this as a human response to a divine injunction in Genesis. Others (perhaps of the non-biblical persuasion) appeal to the scientific progress of modernity. Far more than ever before, we can understand, harness, and even re-direct nature to our own determined ends. In either case, when dominion becomes self-interested domination, we are seeing (clearly, if sadly, in the rearview mirror) that this model of custody is simply not sustainable.

Climate change is just one symptom of an unsustainable consumption and wasteful use of resources, compromising present and future flourishing of human and non-human species alike. Other symptoms include the alarming rate of species extinction, destruction of forests, and desertification. To paraphrase the Catholic broadcaster Mary Colwell, climate change is not the only “environmental” game in town.

The poor are first to suffer when it comes to any and all forms of environmental degradation. This is the case with rising sea levels, and increased typhoon risk due to climate change. But it’s also the case when it comes to social and political instability, caused by issues like water scarcity. Consider: when a country experiences resource shortage or instability, who has easiest access to water, the well-to-do or the poor? Who has the ease of mobility to find (and procure) clean resources? Impacts on human health — e.g., from air pollution or rubbish accumulation — disproportionately affect the economically disadvantaged. We might also consider the plight of indigenous people who are functionally evicted from their land and forests to make way for mining activities or logging. The encyclical will likely talk about care for the environment through the lens of solidarity with the poor. In doing so, it will critique the shadow side of our consumerist economic models.

Such a critique is nothing new in Catholic thinking. It simply picks up and develops Benedict’s notion of the disjuncture between human ecology and the natural order outlined in Caritas in Veritate. Christiana Peppard puts it nicely in her article for the Jesuit magazine America: whilst Pope Francis has a “special charism for poverty and the environment, he is not inventing it ex nihilo, he is amplifying the unified message of his papal predecessors.”

2. Climate change “propaganda” – According to whom?

Much of the rhetoric leveled against the forthcoming encyclical emanates from pressure groups that deny anthropogenic climate change. Take for example the US based Heartland Institute, which is urging its supporters to “tell Pope Francis global warming is not a crisis!” They are highly critical of the Pontiff’s frequent calls for action over climate change and were especially dismayed by his personal involvement in the Lima Climate Change talks in December 2014.

The Heartland Institute is keen to spread its message. On April 27 it held a gathering in Rome to persuade the Pope that he has got it all wrong about climate change. The meeting was deliberately timed to coincide with a Vatican-hosted conference on the moral dimensions of climate change that took place on the following day.

Now I couldn’t possibly comment on the underlying agenda of these lobby groups (their sources of funding, for example) but it’s worth noting the short shrift Church leaders have given them: “The ideology surrounding environmental issues is too tied to a capitalism that doesn’t want to stop ruining the environment because they [certain movements in the United States] don’t want to give up their profits,” quipped Cardinal Oscar Rodríguez Maradiaga, who is a member of Francis’s so-called C9, a kind of ‘papal cabinet’ of nine cardinals from around the world.

Pope Francis has taken a keen interest in those with first-hand experiences of the effects of climate change. During his visit to the Philippines in January 2015, he made a special point of visiting victims of typhoon Haiyan. The significance here is that he is more interested in the voices of those who have everything to lose from continued ecological destruction, and is less concerned with those who have something to gain in promoting a “business as usual” approach.

3. The Church is not walking into another “Galileo Affair”

One strategy for undermining the encyclical is to overemphasize the unsettled aspects of the science of climate change and give stage to a minority group of scientists who question anthropogenic climate change. The reasoning given is a fear that the encyclical will commit the Church to an unsettled hypothesis of science, and thus irrevocably fetter the Church to the wrong side of history. Climate change skeptics (it is argued) pick up the heroic mantle of Galileo, whose heliocentrism eventually was proven correct to the shame of credulous Church officials. Thus the Church should cautiously refrain from landing — once again — on the wrong side of history.

The problem with this view is that it portrays climate change as an either/or issue between “self-interested alarmists” and “truth-speaking skeptics.” The reality is more complex. Social encyclicals (like the sciences themselves) seek to present the best thinking of the Church at the time. It is reasonable for Francis — whose own academic background is in chemistry — to side with the scientific consensus (including his own Pontifical Academy of Sciences) on the link between climate change and human activity.

And let’s face it, the stakes are pretty high. Withholding action (on the specious grounds of awaiting unanimous scientific agreement) is a risky strategy. There’s a justice issue here. As Cardinal Turkson says, whilst the Church is not an expert on science, it is “an expert on humanity – on the true calling of the human person to act with justice and charity.” The just and charitable person errs on the side of caution — especially when the well-being of the poor and vulnerable may be at stake.

4. Regardless of our preferences, the encyclical has something to say to everyone.

A more nuanced strategy taken by critics is to relativize — and thus minimize — the encyclical’s potential application. For example, the eminent Princeton law professor Robert George highlights the distinction between papal pronouncements concerning moral norms (binding on Catholics) and statements about disputed empirical fact (not binding). The argument is that since climate change is a question of empirical fact, the faithful are not bound by those parts of the encyclical relating to climate change.

But we make prudential judgments on how to interpret empirical facts — and derive from them moral norms — all the time. The “theory” of anthropogenic climate change rests on the established fact of our reliance on non-renewable resources. Our current dependence on carbon-intensive forms of energy raises a whole host of underlying moral issues: Not just questions like “Who should profit from their extraction?” or “Whose resources are they to keep, share, exhaust, etc.?” But more deeply, “To what shared first principles do we appeal when we disagree in our judgments of how to use finite resources?” The environmental and social impacts of e.g., mineral extraction, necessarily raise questions of prudential judgment about competing interests; and how we come to render prudential judgments requires us to reflect on our underpinning (if unspoken) moral norms. For people of religious belief, moral norms draw from the well of faith claims, in order to reflect on empirical facts and make prudential judgments. For Catholics in particular (like Pope Francis or Professor George), environmental issues deeply involve the non-negotiable moral norms of care of the human person (because of our inalienable dignity, having been made in the image and likeness of God).

So in the end, we cannot realistically draw a solid black line between (1) what the Pope says about climate change, and (2) what can be regarded as “real” moral issues. Though we may be tempted to do so, we cannot nuance our way out of the moral demands presented in the encyclical, because they bear on the well-being of the human person.

5. Collective action on the environment is inherently Catholic.

A major bugbear of libertarian critics of the environmentalism is that a response requires international collectivist action. As Michael Winters has pointed out, they were are highly suspicious of Francis’ COP-20 address when he said that the challenges of climate change can only be confronted through “collective action” which overcomes mistrust and fosters “a culture of solidarity, of encounter and of dialogue”. Surely, they ask, there is an anti-business and socialist agenda at play here?

And yet this is not what business leaders are saying themselves. A recent Vatican-sponsored conference for business executives, academics and civil society leaders underlined support for just the sort of collective action on climate change the Pope is calling for. Ecological meltdown can only be prevented through a framework of global governance that will stimulate enterprise and develop innovative solutions. A ‘green economy’ incentivizes initiatives like the development of the Solar Impulse plane, which made its maiden voyage earlier this week.

The Church, as the world’s oldest and largest international organization, is uniquely placed to shepherd a collective response to environmental challenges. The Church can help forge what Benedict’s Caritas in Veritate described as more “fraternal” ways of doing economic development. The agenda here is strictly Catholic, geared towards universal human flourishing rather than narrow political ends.

6. Read it, absorb it, and talk about it!

Now I know we all lead busy lives and the general principle of “why read it first-hand when you can rely on another’s summary?” works pretty well more often than not. But this encyclical is different. Given the partisan nature of the reporting in the lead up to the document, the summaries that will be doing the rounds when it is finally released will be particularly agenda-driven. So go to the source — read the encyclical itself. And before reacting, meditate on the text with the same spirit of magnanimity with which we would hope our secular counterparts would receive other Church pronouncements.

Underlying the fears of many intra-ecclesial critics of Pope Francis is a lurking suspicion that he is yielding too much to secular peers. His fans, on the other hand, argue that Francis is seizing an opportunity to make bridges with those outside the Church on a challenge confronting the whole of humanity. But Francis’ fans and detractors alike recognize that the whole ecology debate is characterized by divergence and line-in-sand drawing. As in other politicized issues, the various “actors” are prone to simply talking past each other, relying on settled political allegiances and truisms. And there is a real danger that this polarization is being brought into the Church in the interest of expediency. So tolle, lege: pick it up and read it yourself, as a responsible citizen and Catholic!

* * *

In our reactions to Pope Francis’s ecology encyclical, let us aim to be conduits for dialogue and see it as our mission to “reconcile the estranged.” Reconciling the estranged is, after all, one of the founding goals of the Society of Jesus. The world may very well depend on it.