I teach a student who has absolutely no business knowing what he knows about the blues. In perfect detail, he can describe the different types of blues scales and how they differ from the standard diatonic, or major, scale. After I had simply asked why a blues clip I played sounded different from a popular rock song my students listened to, he shouted, “They use different scales!” I simply expected someone to say, “It sounds different” or, “It sounds sad.” Instead, I was witness to a primer on music theory.

We had been reading Reservation Blues by Sherman Alexie. The novel looks to synthesize the cultural legacies of African Americans with the Spokane nation in Washington and uses the blues as the common language to bring the two together. It opens with Robert Johnson at a desolate intersection on the Spokane reservation.1

welcomia / Shutterstock

Both Johnson and the reservation are at a destination far outside the popular experience of the country, but this destination is not just geographic. In a sense, Alexie locates the juncture as an interior one and uses the toolkit of the blues and his own tradition to find direction at this particular directionless juncture.

In effect, Alexie writes a spiritual treatise, and he uses the mechanics of the blues to do so. Just as his characters stand at vacated interior locations, every human at some point loses direction and feels far from what was once certain and defined.

To help map out a decision at such a point, Alexie incorporates the idea of the blue note. Instead of presenting a linear narrative, Alexie shapes his plot in the likeness of a blues song, with fits and starts that make the reader’s heart jump. As a point of comparison, John Lee Hooker’s “Hobo Blues” lingers, reverberates and even haunts the listener, just as Alexie’s novel does. One thing that helps the music linger is the use of the blue note.

Blue notes are often subtle, but nonetheless able to grab and re-direct the listener’s attention. They use minor, or “sad” sounding notes, to move to a different part of the scale and continue the project of the song.

The blues have proven to be a great spiritual resource for me over the last few years, particularly because of the existence of these blue notes. When feeling uninspired in my work or weighing the choices between two equally great or horrible decisions, from choosing a major to determining the extent to which I want to collaborate with those who disagree with me, the blue note helps guide my spiritual musings. The blue note offers a lens through which to view the stuff of everyday life and cherish the meaning it communicates to me.

I look to the blues as a resource for spirituality because it dwells on the liveliness of bothSaturday nights and Sunday mornings. The energy created by encounters and relationships at these two times initially seem quite distant: one focuses more on entertainment and socializing; the latter usually carries with it an air of rigidity. The two seem like polar opposites, but it’s the blue note that helps me navigate both worlds. Not only can I exist in these worlds, but I can engage them, especially by bringing the same fervor I have at a blues gig to my worship the next morning.

Not so long ago, I was struggling with feeling no connection to either my workplaces or those activities that once filled me with excitement. Needless to say, I did not have much attraction to either the frenetic energy of Saturday night shows or to the solace that Sunday morning typically brought. I was stuck at a place that I did not recognize, and I lacked direction on which way to travel.

So, having stalled in this unfamiliar state, I turned to what had previously brought some clarity: the blues. This time, I had someone to help guide me through what exactly the blues were supposed to do.

A professor of mine explained that the blue note worked in the music the same way that desires work in my life. Whether that desire be for wholeness or direction, it is a desire that subsists both in the nightlife of my Saturdays and the worship of my Sundays. He encouraged me to take hold of that feeling of being without direction and allow it to reverberate, just as those blue notes reverberate in my memory after the song has finished. Doing so would allow me to identify what that void was, but it would also allow me to see what housed that sound in the core of myself.

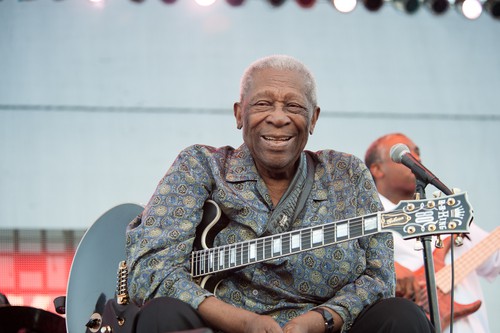

Randy Miramontez / Shutterstock

Blue notes are “flattened” notes. They have a unique purpose in the blues scale, but they do not comprise the entire scale. Rather, they serve to complement or accentuate the scale and so heighten the tones that lie therein.

Just so, when the protagonist of Reservation Blues sees Robert Johnson on his reservation, he calls out to him, “Are you lost?” “Been lost a while, I suppose,” is how Johnson responds. As he speaks, the narrator explains how “His words sounded like stones in his mouth and coals in his stomach,” which compels him to address a hunger for wholeness that Johnson has.2

Sherman Alexie and and countless others use the blue note in creative ways to give direction to their audiences as they look at the world and wonder how to engage it. Blue notes, therefore, help us navigate all dimensions of our lives, and when we inevitably feel like Johnson from Alexie’s novel, the notes will still reverberate in our memories and direct us once again.