Olga Lossky

We’ve tried to cut a wide swath in our selection of interviewees for the Catholic Writing Series. We’ve polled poets, critics, and writers of fiction and memoir. We’ve spoken to men and women. We went beyond these United States, to our neighbor to the north. And this week, we’ve gone even farther outside the proverbial box. Olga Lossky hails from France, and is an outlier among our contributors in an important sense: She is of Orthodox Christian background. And her religious heritage, as we will see, makes a generous contribution to her work, giving her something in common with our other authors of faith. So first off, many thanks to Olga for being a part of our project.

Nicolas Steeves, S.J.

Olga came to our attention via a good Jesuit friend from my days in Rome. Nicolas Steeves was born to an American father and a French mother in Paris, France. He immediately moved to the snows of Vermont and the woods and ponds of the Boston area. He left the US again as a child for the vineyard-covered slopes of Southern Burgundy, France. Playing the piano and reading novels at night helped him through adolescence. He gave up being a financial lawyer and joined the French Province Jesuit novitiate in 2000. For better or for worse, his big mouth and imagination did not stay at the novitiate door: They marched in with a love for good preaching and singing. Nicolas has just completed a doctoral dissertation on the role of the imagination in Fundamental theology at Centre Sèvres-Jesuit Faculties in Paris and will go on teaching at an academic and a popular level, particularly with young adults. Although he enjoys speaking with friends and preaching, he is also amazed at the grace of hearing confessions and listening as a counselor and spiritual guide.

Nick and I met in Rome in 2009, when we were both students at the Gregorian University. On occasion we would wander over to Trastevere, drink a few beers, and talk literature. Naturally, his ears perked up when he heard that TJP was moving this series forward. As Olga is a personal friend of his, he tossed out the idea of including her in the lineup. Nick then recorded a live interview with her, transcribed it, and translated it into English. So we also have Nicolas to thank not just for broadening the horizons of the Series, but for his monumental effort in getting this interview to e-print.

I’ll now hand the mic to Nick. Enjoy his chat with Olga. And as usual, keep the conversation going.

__________

Olga Lossky was born into a family of Orthodox theologians of Russian descent, in Paris, France, and grew up in Dordogne, the French South-West. After studying literature, she began work in the free-lance publishing sector, and particularly in the genre of religious writing. She drafted a biography of the Orthodox theologian Elisabeth Behr-Sigel, Toward the Endless Day, in 2007. She has also written and published three novels, Requiem pour un clou (Gallimard, 2004), La Révolution des cierges (Gallimard, 2010), and La Maison Zeidawi (Denoël, 2014). Her two first novels were published in the prestigious (and not especially religious) “NRF” collection at Gallimard. Her biography of Behr-Sigel has been translated into English, but her novels haven’t… yet.

__________

Nicolas Steeves: Your third novel, La maison Zeidawi (The House of Zeidawi), is hot off the press. Now, English-speaking readers might know your well-received biography of Elisabeth Behr-Sigel, Toward the Endless Day (University of Notre Dame Press, 2010), but your novels haven’t been published in English yet. Could you tell us something about them?

Olga Lossky: My first novel, Requiem pour un clou (Requiem for a Nail), was published ten years ago. It’s the story of an old man who lives in a communal apartment in 1950’s Moscow, who, one morning, finds a nail in his shoe sole. Since he’s a hoarder, he refuses to throw the nail out and just bangs it into his wall. Now, since it looks ugly, standing there alone on the wall, he finds a painting at the back of his closet and hangs it up. Then, he starts daydreaming in front of the painting, which represents a church with people streaming out of it, in the Russian countryside, pre-Revolution. He daydreams so intensely that you lose track of reality. Is reality in the painting, which depicts the story of a young man during Holy Week, who leaves to find his missing father, a painter? Or is it in the shared, overcrowded apartment this old man lives in, a place in which he feels so strangely isolated? The novel constantly moves back and forth between both stories, which kind of mirrors the more general mise en abyme a reader experiences when reading a novel.

NS: You mentioned a church with people streaming out of it. Is religion very present in your novels as a thematic element?

OL: Yes, it is, but in practical senses. It shows up almost involuntarily. My first two novels take place in Russia, so the cultural context calls for it; the Orthodox religion plays a narrative role. In my third novel, located in Lebanon, it comes back in a different form. But it’s also my personal history—religion is a very familiar environment to me.

NS: But at the same time, your novels aren’t strictly speaking religious novels. The central character is never, say, a priest.

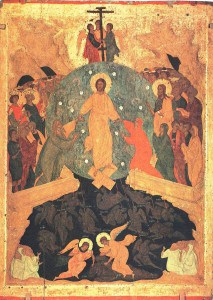

OL: Well, can you call a novel “religious” just because the main character is a priest? Is The Passionate Heart (ed. note: a 1953 novel by B. Beck and 1961 film: “Léon Morin, Priest”) a religious story? It’s not as if I aim to promote some sort of Christian apologetics in my work. In my second novel, La révolution des cierges (“The Church Candle Revolution”), one of the two main characters is a monk, who paints icons. Religion, Orthodox religion, is present as a narrative factor, but not—at least, that’s how I see it—not in order to promote religion through outright apologetics.

NS: From my standpoint as a Catholic reader from the Latin tradition, my impression is that your novels present the faith somewhat indirectly, like flashes of light bouncing off icons, like gold just shining there, a ray of sunlight… You put a strong accent on the Resurrection, don’t you?

OL: I try to represent Life—life in its reality, its grittiness, its gashes of hope coming from elsewhere, stemming from a lack, from a yearning, from a quest for something else. I try to show that this quest sometimes yields fleeting moments of communion with something else, something transcendent. The interest of the monk character in my second novel lies in his faith journey. As you read the novel, you find that he became a monk, not by vocation, but through a chaotic life-path which made the monastery a safe haven where he could exercise his artistic activity. But at the same time, painting icons is not just an “artistic activity;” it has a very strong theological foundation. So, what I like to depict is the ambiguity of our faith-bound travels: We’re never completely sure, we’re ridden by doubts, question, perplexities. It’s that kind of scene that I enjoy presenting to readers.

NS: How do you see Christian writing—whether Orthodox or not—in France today? France has a reputation as a very secular country, after all. Have you experienced difficulties as a novelist who is a believer?

OL: To give a bigger picture, I think there are two types of “Christian literature”. There’s a Christian literature, more like essays, geared for believers, which, so to speak, preaches to the choir. In France, this was the like of such big figures in Orthodoxy as Olivier Clément – of course, they don’t speak exclusively to believers, but they broach topics of faith in explicit ways. They touch believers first, and then hope to touch others beyond faith. Today, we have philosophers in the same vein, like Bertrand Vergely or Fabrice Hadjadj—people who really place the question of faith at the center of their work. In fiction, by contrast, it’s tougher to follow that line. Fiction obeys other rules, where, first of all, you write whatever comes out of you. You write from your inner motions and emotions, not necessarily to witness to your faith–at least, not consciously.

NS: How open, do you think, is our culture to the kind of literature that presents God, religion, and faith more explicitly? Are we in a situation where, as Flannery O’Connor said, writers have to shout for the deaf and draw large figures for the blind, or is a writer of belief better off presenting God’s call in more subtle ways?

OL: I think that God’s call today cannot be explicit. At least, that’s how I feel. People are so fed up and distrustful of a cultural Christianity that even vaguely relates to God or religion often triggers suspicion. This situation, however—secularization, post-Christianity, laïcité, whatever you call it—is a great opportunity. We’ve come back full circle to Christian origins, to a world like the one the Apostles were sent to preach to, to an uncharted land that isn’t antagonistic towards a religion that has been exploited, or that has lapsed so often into communitarianism, or that has led to so much bloodshed in all our Christian denominations. There’s a spiritual thirst today at all levels, a yearning for something else. That’s where a novelist with strong Christian beliefs can pitch in and help out.

NS: You bring a lot of your own background into your work. But given how unfamiliar – even exotic – this background may strike readers here, how do you handle things so that the Russian, Lebanese, or Orthodox facets of your novels don’t end up sounding like folklore?

OL: I really write what comes to me… I really strive so that my writing is inspired, in the strongest sense of that word. Writing is truly ascetical. It’s a constant struggle, and I’m constantly aware I’m still far from the finish line, so to speak. I really have to let myself be crossed by a stream greater than I. Although my writing obviously includes personal and biographical facets, it should also open up to something larger. The most important thing for me is life, the life of these characters, and not just stereotyped details. These characters must be incarnate.

NS: Do you think your Orthodox faith perhaps makes your novels less cerebral than Catholic ones? Or is this question too caricatured?

OL: Well, things vary from author to author. I personally don’t write romans à thèse [didactic, theory-based novels]. I don’t start out thinking, “I’m going to prove this point,” or, “I’m going to build a plot to prove a point.” I generally start from real life. What always comes first to me are characters. Then, I try to build a plot that will reveal their truth, to show real life, to show a faith that takes flesh in characters who are torn and troubled, and struggle—in our own image.

NS: Compared to the “fall and redemption” Western model of salvation, which we got from St. Augustine, do you think your storylines run down another road of salvation?

OL: (chuckling) I have to think about this… (pause) Well, there is something I highlight in my novels, because it’s just so fundamental for me: the central character of Christ’s Resurrection. Especially in The Church Candle Revolution: The icon the monk is painting represents Christ’s Harrowing of Hell. For me, that is the central event of faith. And I want to draw all of its consequences for us, direct or indirect. In my third novel, a man goes on a quest to establish his sonship, to find his ancestry in Lebanon. I want to highlight this central aspect for faith, especially in Orthodoxy: divine sonship, the idea that, in order to become God, you have to acknowledge you’re a son of God. That’s the main tenet of Orthodox soteriology – divinization. Maybe that’s something specifically Orthodox.

NS: You mention the icon of the Harrowing of Hell in your second novel. Actually, I think that image is present in all your novels. Is it some kind of implicit posture for you? In today’s world, must a novelist descend into hell like Christ?

OL: I actually think it’s a vital dynamic that concerns all of us. All of our life journeys have that turning point. When he descends into hell, Christ arrives at the lowest point possible, and it’s from there that life springs forth. It’s this whole paradox. Our lives are really built on that paradox – when we’re at the lowest point possible, when we run into really tough times, a light will, or can, burst, because you surrender into the hands of Someone greater.

NS: You’re a woman, a wife, a mother of two sweet girls. Does that impact your writing?

OL: Of course it does, insofar as writing is fed by life, and by our personal lives. Then… remember earlier, when I mentioned asceticism? There’s a whole struggle in the writing process, since our writing stems from really personal stuff – a struggle not to be narcissistic or complacent. As humble as it may be, something universal crosses our lives, through the everydayness of events, something of the spiritual travels I am called to go on with my family shines through.

NS: How does being a woman mark your writing?

OL: Well, the surprising thing is that, though I’m a female writer, my three main characters are men—except for The Church Candle Revolution, where there’s also a woman, and then there are strong female characters in The House of Zeidawi. Does being a woman really influence my writing? That’s a tough question… (pauses) Actually, I think motherhood gives some kind of sensitivity, motherhood makes us touch the mystery of Life very closely. Of course, a dad also feels the mystery of Life, but motherhood makes you feel completely overwhelmed. There’s an incredible paradox and a sense of awe and wonder there. A woman writer can testify to that—this amazement in front of Life. Then, each author, male or female, is much more than just that. Actually, I’d like to return to one issue we raised earlier.

NS: Sure.

OL: Literature today touches fewer and fewer people out there, and perhaps mostly people who have already taken sides. I realize that my readership is very homogeneous – they’re part of an older, still-Christian generation. You’ve got to be realistic about your actual witness to the Gospel. Maybe there’s a crucial point here: We shouldn’t just indulge in doing things we’re comfortable with, or addressing people who are already on board with us. There’s a real work to be done today, to become, as St. Paul says, “a Jew unto the Jews” (1 Cor 9:20) and a Greek unto the Greeks, through literature. We should adapt our style, our plots, to the people who thirst, and whom we might not be feeding enough.

NS: What kind of path would you pursue in that respect?

OL: To start with, my style is very classical, even heavy. I think that today, with the great drive to speed everything up so much, with our constant zapping, people won’t buy into that kind of literature. We have to try and simplify things, without caving in to over-simplification, either.

NS: Are there contemporary authors you find inspiring in that regard?

OL: I just don’t read enough contemporary literature. (laughing) I’m too stuck in Dostoevsky! Earlier novelists are inspiring, but they’re also from another time and place. Actually, there are true Christian authors out there today like Christian Bobin or Christiane Singer who have readers. But even their public is small.

NS: Hmm… Should you move towards writing screenplays? Or stay in literature?

OL: Well, I would stay in literature. But it means you have to work really hard to analyze what you’re doing, and to figure out what the general public needs—answer them, but remain yourself… Is this even possible?

NS: (laughing) One last question: When you die and reach the throne of the Divine Majesty, is there something you’d like to say to God? Or hear God say to you? Can a novelist imagine that?

OL: (chuckling) Well, for a believer, our Judgment happens now, at every second of our lives. We’re standing before God at every moment and asking, how can I get close to you? What haven’t I done to be closer to you and to others? For me, Judgment is now.

__________

Translation of Olga Lossky, La Révolution des cierges (The Church Candle Revolution)

Gallimard, nrf, 2010, p. 146-147

He had never longed to be a monk. It came by chance, at a time in his life where only a radical decision could tear him from despair. The old storms were appeased now; maybe it was time to start afresh. God, who was all Love, would forgive him his indecision. At any rate, if he chose to leave, he would be acting out of charity; it would be to help his relatives, to support the mother he had neglected for twenty-six long years out of the world…

The paintbrush was dry and lifeless in Father Gregory’s hand when Vespers rang. The bell made him jump. He considered the walls of the workshop with an eye that was surprised to still be there. To leave… Was it only a daydream or a real decision? “Leave!” shouted a voice inside of him. To join them as fast as he could – that would be his destiny. That certainty bore down on a mind which, through reminiscing, had already been led far away from the monastery.

His gaze alighted on the icon in process. Leave? Abandon this icon unfinished? Yes, that would be a true act of self-denial, the finest. This icon-in-preparation he would take with him, he would proclaim it to the world in pain. That would be the true way to finish this icon: to make the Resurrection alive in the heart of men. His time of retreat was nearing its end and God was calling him to return to the world to bring it the good news, as Christ, after forty days in the wilderness, had returned to his fellow men.

___

Il n’avait jamais désiré être moine. C’était venu par hasard, à un moment de sa vie où seule une décision radicale pouvait l’arracher au désespoir. Maintenant les anciens orages se trouvaient apaisés, il était peut-être temps de commencer quelque chose de neuf. Dieu, qui était tout Amour, lui pardonnerait son irrésolution. D’ailleurs, s’il choisissait de partir, il agissait par charité : c’était pour venir en aide à ses proches, pour soutenir sa mère qu’il avait négligée durant ces vingt-six années hors du monde…

Le pinceau était sec et inerte dans la main du père Grégoire lorsque les vêpres sonnèrent. La cloche le fit sursauter. Il considéra les murs de l’atelier d’un œil étonné de se trouver encore là. Partir… N’était-ce là qu’une simple rêverie ou une décision bien réelle ? Partir ! criait une voix en lui. Les rejoindre au plus vite, telle devait être sa destinée. Cette certitude s’imposait à son esprit, que l’évocation du passé avait déjà mené très loin du monastère.

Son regard se posa sur l’icône en cours. Partir, abandonnant l’icône ainsi inachevée ? Oui, ce serait un véritable acte de renoncement, le plus beau. Cette icône en chantier, il l’emportait en lui, il la proclamerait au monde en souffrance. Voilà quelle serait la vraie manière de terminer cette icône : rendre la Résurrection vivante dans le cœur des hommes. Son temps de retraite touchait à sa fin et Dieu l’appelait à retourner dans le monde pour y porter la bonne nouvelle, de même que le Christ, après quarante jours au désert, était revenu vers ses semblables.