During my first days in Brazil I lived behind a series of doors to which I had no keys. I could get to my room at night and could leave in the morning, but because of the sequencing of the doors and their locks, I could not return to the kitchen after heading to my room. Being as I was in a new place, unsure of the schedule from day to day, and without immediate access to any cash or food, I did the only reasonable thing. I began to hoard.

My hoarding was nothing worthy of an episode on TLC, but as I left the kitchen each night after dinner I’d covertly put an extra piece of fruit or bread into my bag along with a can of soda, a water bottle, and a handful of candy from a jar by the phone just to be safe. I was nervous. I was in an unfamiliar place. I was vulnerable. I was foolish.

At the time it seemed a sensible thing to do, but I can tell you quite plainly that it was done in fear and fear is rarely reasonable. I was hoarding to avoid hunger, but my fears were unfounded. I was fed generously and regularly. On my last night in that house I sheepishly packed the surplus food into my bag and pretended the whole thing never happened. The people of Brazil were more than kind. In fact, my “fat pants” are back in business thanks to them. Obrigado, Brasil. Muito obrigado.

We become anxious when we fear that there won’t be enough. Of course, this isn’t just true of food. I worry about all kinds of scarcity. I worry that I won’t be able to do what I’m asked. I worry that somehow the rug of security will be pulled out from beneath me, that my creativity will tap out, that I’ll reach my breaking point. Yet how many people make something, a living, out of far less than I waste in a day? I’d rather appreciate the abundance in which I spend most of my life than worry that I won’t have enough, that somehow my life is insufficient.

Worry is a waste. If we want to keep our worry in check we ought to spend more time with the worthless and the wasted. We ought to spend the time we waste in worry with the poor and those who suffer.

***

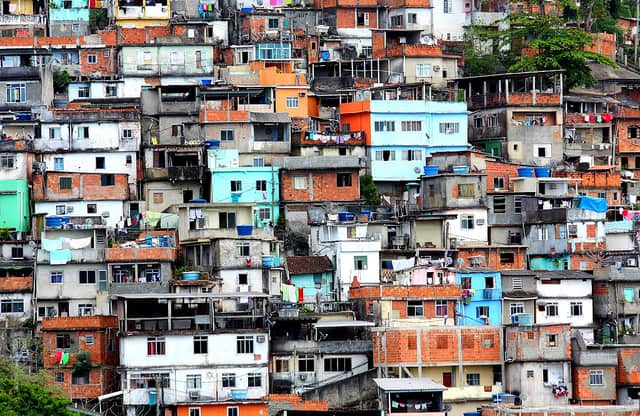

On the way to the airport as I left Brazil I spotted again and for the last time the famous favelas of Rio de Janeiro behind the boundary fences lining the highway. When I first arrived in the city I noticed the piecemeal brick buildings with flat roofs and dogs chained to their exposed rebar. I noticed kites flying above the fences like a playful communique from the other side. These neighborhoods were overflowing with the outcasts and the extras, with the city’s worthless surplus, the ones from whom the bounty is withheld, the ones for whom we never have enough. The many. The marginal. The wasted.

Like most cities, Rio is marbled with these extras. They live in alleys and underpasses. They piece a life together one brick at a time without capital investments, inherited wealth or advances. They scrape, they gather, they mob, they scramble. They create a life where there is none. Rarely is it the life I would want, let alone the life anyone would choose, but there is a captivating beauty about the way their life rises ever so slightly from the dust. Again and again I’m enamored of how both smiles and tears break loose from their hardened faces. As I worry about not having enough I am graced to notice the beauty in this surplus.

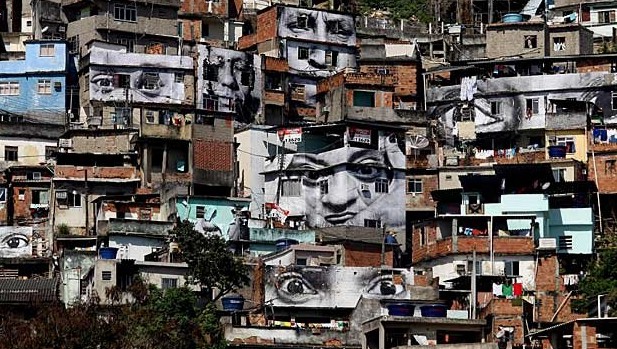

To fall in love with the poor is to risk romanticizing their suffering, but to completely avoid this risk is to avoid loving at all. One thing ought to be clear – the beauty of the poor is found not in their poverty but in their perseverance. Love of the poor ought not to romanticize their humiliation but rather recognize their humanity. Love banishes fear and my fear of scarcity was eased somehow when I discovered again the strange beauty of the marginal, the liminal people, the ones behind our locked doors and fences, the ones we only see out of the corner of our eye.

The church’s preferential option for the poor suggests that we should stand with them, reverence them, listen to them, invest in them, learn from them, and act for them. But too often all we are able to see in them is the life we don’t want, the struggles we pretend to avoid, and the vulnerability we are eager to banish. In this willful blindness we suppress and we hoard, we deprive and rob, we smother and trample. We push them down and kick them out. We ignore the bare fact that somehow it is their life, their work, their struggles, and their backs upon which our lives are built.

They are the surplus. They make from the mud what we presume to have pulled from the sky. They are the creators crucified. They reveal a divine severity on which our fragile lives depend. They live very close to death and from that place they stand witness to the miracle of life.

***

When I worry that there won’t be enough I hope to remember those who make something from nothing. I hope to notice the many ways in which I’m privileged with plenty. But even more than this – and here is where I fail more than I succeed – I hope to give it all away. The antidote to poverty is not wealth but generosity. The antidote to fear is not worry but surrender.

When I’m free enough to give everything away, to let go of the fear of scarcity, when I’m free enough to want for nothing, then, as the psalmist says, God will be my shepherd and there will be nothing I shall want. Moreover, when we all want for nothing there will be no one left wanting. When we accept the surplus instead of wasting it then we’ll have discovered the beautiful truth of life in abundance.

To move from worry into hope we must avoid the foolishness of hoarding and embrace the freedom of generosity. We must love in the mutuality of vulnerability. We must move from the fear of scarcity into the fullness of life.

***

The cover image, from Flickr user Daniel Julie, can be found here.