On Halloween, I watched “The Exorcist” (1973) with a couple of Jesuits to ring in the succession of feast days that November brought—All Saints (Nov.1), All Souls (Nov.2) and All Saints and Blesseds of the Society of Jesus (Nov. 5). Even after forty years,“The Exorcist” continues to make grown religious men cry out for their holy water bottles. Though, as far as I know, none of us actually cried later that evening, some of us did have trouble falling asleep, hearing over and over in our heads that monumental line from the movie: “The power of Christ compels you.”

Frightening though he may be, the Devil is bewitchingly captivating. It is no wonder that “The Exorcist,” based on Peter William Blatty’s book and directed by William Friedkin, still is arguably one of the most popular scary movies of all times. No matter where we stand in terms of religion and piety, the Devil – personified evil and despair – enthralls us. In fact, 63% of Americans between the ages of 18-29 believe that demonic possession is possible. Curiously, like Saints, Angels, and Holy Souls, demons also titillate our imagination and point us to a reality that our senses grapple with but cannot pin down.

“The Exorcist,” for those who haven’t seen it, tells the story of a possessed 12-year-old girl whose condition confounds experts in the medical field. Hollywood special effects and over dramatization aside, the film deals with faith’s desperation in the face of uncertainty. After exhausting all her options, the girl’s skeptical mother seeks help from a young Jesuit priest who is also a skeptic trained in psychiatry.

Ironically, of all things, the Devil brings together faith in scientific reasoning and faith in a supernatural order and makes believers out of skeptics. Rather than simply acting out of fear, hanging over the window ledge of despair, the characters in the movie turn to the ancient prayers of the Catholic Church, either as a psychological or spiritual aid, for a final attempt to find hope and healing.

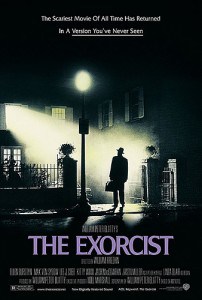

The Exorcist movie poster

Though this movie is often categorized as a “horror film,” it was not the intention of the author and director to produce a horror movie primarily because they sought to allude to the actual story of the exorcism of a desperate Lutheran boy in St. Louis in 1949. (More info. on the most famous exorcism in the United States performed by Jesuit Father William Bowdern, S.J. here.)

Inspired by actual events, the horror of “The Exorcist” lies in its realism. J.C. Macek, III, from PopMatters would agree: “The Exorcist was not approached as a horror film, but as a spiritual mystery and drama. The lack of jump-scares in Friedkin’s classic make the suspenseful, visceral terrors all the more real for the viewer….To the engrossed viewer, The Exorcist isn’t a horror film, The Exorcist is horror.”

The Devil, or at least the horror we attribute to him, is real. (See here for Pope Francis’ take on the Christian response to the Devil’s reality.) Thus, the idea of the Devil can in a sense serve as an icon that calls to mind the “mystery and drama” of life in which we all desire at our very core some degree of hope for something or someone bigger and more real than that destructive and despairing force that we face daily. There is no horror greater than the horror of despair, and from this angle, even the thought of the Devil, the possibility of ultimate despair, can keep hope alive in that bigger reality that does indeed compel him.

******

Cover Image courtesy Flickr user Insomnia Cured Here, found here.

The Exorcist poster image courtesy Flickr user K嘛