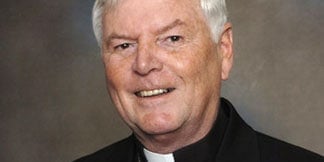

Bishop O’Kelly by Jim McDermott, SJ

Author’s note: After decades of work running Jesuit schools, in September, 2006, Greg O’Kelly, S.J. was named the auxiliary bishop of Adelaide in the Australian state of South Australia. He was Australia’s first ever Jesuit bishop. Three years later, he was appointed bishop of the Port Pirie diocese, one of the largest and poorest dioceses in country. While working in the Port Pirie diocese during the summer, American Jesuit Jim McDermott, S.J. interviewed Bishop O’Kelly, S.J. about being a bishop today.

Tell me about your diocese.

The Port Pirie diocese is 1 million square kilometers – the same size as France and Germany put together. But it has many more kangaroos and camels and donkeys than Christians!

The diocese has many ties to the Jesuits. The pioneer priests here were Austrian Jesuits who had been expelled from their country in 1848. Over the years Jesuits built 34 churches in South Australia, starting from their mother house in Sevenhill [which today boasts the only remaining Jesuit winery in the world]. They worked very closely with the Sisters of St. Joseph, founded by St. Mary of the Cross MacKillop, Australia’s first saint. Her brothers went to our school at Sevenhill, and one of them became a Jesuit who worked for years with aboriginal people in the Northern Territory as Superior of the Jesuit Mission.

We would be the least resourced or the second least resourced diocese in Australia. The bishop’s chancery consists of four employees, including the business manager and the bishop’s personal assistant. Most of our administrative work has to be done by people with other jobs; we don’t have the resources for an office for youth ministry, liturgy development or social justice issues. We have to farm that out amongst ourselves. When I was appointed to this diocese the Jesuits were happy, too, because they believed it to be a challenging, even missionary appointment, and our origins were here.

We have huge challenges with our aboriginal people similar to those of the Native Americans, with inroads of alcoholism, petrol sniffing amongst the young, unemployment and the development of a welfare dependency attitude which saps all drive or creativity. We have not had an ordination for 18 years, and have not had a seminarian for 19 years, but I have been successful in attracting some foreign seminarians and priests through personal contacts.

How did you become bishop? And how did you feel about it?

When I was made a bishop, it came completely out of the blue. I was on the archdiocesan consult in Adelaide but I knew nothing about it [the decision]. It was a period of dismay and bewilderment. I consulted Jesuit friends, but the advice all was I really should go with it, as it had been put to me in terms of obedience.

I had been told that they wanted my experience in education and formation at the Bishops’ Conference, and since that time I have headed the Australian Bishops’ Commission for Education. That’s a significant role in the Australian church because 1 in 5 children in Australia are in Catholic schools. (In the 19th century bishops created a parallel school structure to the government, believing the public schools were inimical to handing on the faith. So there’s a much great investment in schooling than any other western country.)

How did I feel? I said bewildered. Also quite devoid of any consolation. I was being asked to live in someone else’s family. I also came out of a background of being a Jesuit headmaster for 29 years straight, and had no parish experience.

But the people here were very welcoming, and they were delighted to get a Jesuit, they spoke about the origins and the early fathers and brothers.

Uluru

What’s it like to be a bishop?

The consolations are the esteem and affection of the people and the acceptance of the clergy. People are very caring and supportive of me; the priests are no-nonsense, hard-working priests of the Bush, loyal and committed. I move amongst them a fair bit — the size of the diocese demands a lot of time on the road, drives of seven or eight hours one way. To visit the stations (Ranches) and pubs and small settlements on the way to Uluru [a national landmark and aboriginal holy ground], which is also part of our diocese, takes me most of a week by vehicle. I drive about 55000 miles a year in the car, and fly in a small plane to other Outback cattle stations and aboriginal communities.

There’s a strong sense of community here. Our people talk about our diocese, they’re proud of its history; we know we’re small in number and we’re scattered, but our people are very loyal to their priests and strong in their identity as members of this diocese.

Another consolation is the opportunity to work as hard as one can for aboriginal people and for prisoners. We have three major prisons in the diocese, almost 2000 prisoners, and their needs are not vote winners, so the ability to provide care of them through our priests and lay ministers is a real exercise of Church.

The other area that gives me enthusiasm is the work for lay ministry. We’re developing teams of lay people who can rise to the occasion to exercise pastoral ministry and administration of parishes. We have lay people already fulfilling these functions when needed, even the burying of the dead when distance prevents a priest getting there in time.

The desolations are in the way of the loneliness of the job. Many bishops are appointed to dioceses away from their homes, and often have no relations or even friends in the diocese to which they’re sent. My impression is that few people are sufficiently aware of this. The bishop is seen as the top of the pile, and his own personal needs for friendship are often under-appreciated. I’ve been fortunate there’s a Jesuit community about one and a half hours a way, and I do get down there every few weeks.

St. Mary McKillop at the Cathedral of St. Stephen in Brisbane

Being bishop means being where the buck stops, and the most grueling form of that is the dramatic encounters with victims of abuse. The perpetrators are men long dead, but the victims are still alive and very much hurting. It’s an ironic consolation to be able to see the relief of victims when their stories are believed, when they’re made to know that they’re not freaks, that there are other victims as well, and that this individual is attempting to be as helpful and supportive as he can be.

Other challenges can also overcome your thinking, like how to reengage the church with the young, a principal challenge and one faced by the whole Western church. Here however we’re in a situation of small, rural communities; the absence of the young at church cannot fail to be noticed. We have schools that are successful and full but one rarely sees the young at the parish Eucharist.

As bishop, you have bleak moments of helplessness. You can’t answer the questions facing the church by yourself. Sometimes people think you might have a magic wand, but we’re ordinary men trying to do an extraordinary job. But it does have many beautiful moments. We managed to get a married deacon, and ordaining him was a privilege. Ordaining my brother Jesuits is a wonderful privilege, an awesome experience for a bishop. I’m sustained by the support and positive attitude towards me amongst my brother Jesuits of the Australian province. I go to the vacations, attend the province meetings, stay in the Jesuit houses and always make sure people know that I am a Jesuit. I always insist on the SJ in my title, and the people know me as a member of the Society.

For you, what’s the role of the bishop in the church today?

In a diocese like this, it’s probably best summarized by the term “chief shepherd”. I have a real care for the priests: I have priests in their 80’s still working as parish priests, and I have to give care for them. The first call of the bishop today is to be with those priests, to keep them alive to their ministry, to keep them alive to the needs to pray and read. Because a priest who doesn’t pray and read is becoming an ineffective instrument.

Then the care for the lay leadership personnel in the diocese – the school principals, those who work at our home for the aged, the prison chaplains, people working with indigenous people, those who work at Centrecare (which is Catholic welfare), the St. Vincent de Paul society, youth ministry, and so on. The role of the bishop is to keep those people affirmed and to do whatever he can to provide means for them to live their own ministry.

More broadly, the role of the bishop today is to try to present a human and caring face of the church, one that is not proud or arrogant, one that’s conscious of the hurt and evil that’s happened through church personnel, but still wishes to reach out in the spirit of love and service for all people. The bishop is the face of the church for the non-Catholic community and for the media, so it’s very important that he reflect on what image of church he’s projecting. In an age of restorationism that becomes even more so, to indicate the true pastoral nature of the bishop’s role, not the theatrical or fancy dress.

There are some bishops who are content to stay in the world of pageantry, but most are really good shepherds. Some are afraid of pluralism of thought, but for most it’s the pastoral side that governs them. My own attitude is, if you go into a garden you look for flowers. If you go into a garden to look for weeds you’ll certainly find them. So you look for flowers. And they are all always there.

O’Kelly Ordains by Jim McDermott, SJ

What’s your image of God?

The word “Father” is important to me, but I see Christ as the face of the Father. It’s the person of Jesus, he is God become flesh, he is the Companion Lord. He has a name and a face through the stories of the Gospels so that I feel more at home with Him than with the abstractions of the deity in terms of attributes such as infinite, almighty, eternal, etc. God is in Christ, and the face of Jesus is the face of God.

Has your image of God changed at all since becoming bishop?

I’m becoming more attuned to the sense of God as the mover and creator of all things. I take more seriously that line of Ignatius, “Pray as though everything depends on you, and work as though everything depends on God”, which is opposite as to how it’s often said, but it means that God does work through these things. I’m more convinced as bishop that it’s God’s show, and that finally it’s his work. So that whether we succeed or fail in our efforts, ultimately it’s God’s responsibility. We try to work on his behalf, but in the word of the Psalmist we can sometimes say “Stir up Thyself O Lord and come”, especially when dealing with issues that don’t have ready answers.

In the Outback the Creator God does come, because there is that vastness of this land, the scope of the skies, the silence of the outback, the sense of a presence there that you don’t get in the bustling city, the sense that this land is sacred. As John Paul II said on his 1986 visit, we have much to learn as Church from our aboriginal people in that regard.

But the person who gets in the car next to me for the long drives is Jesus.