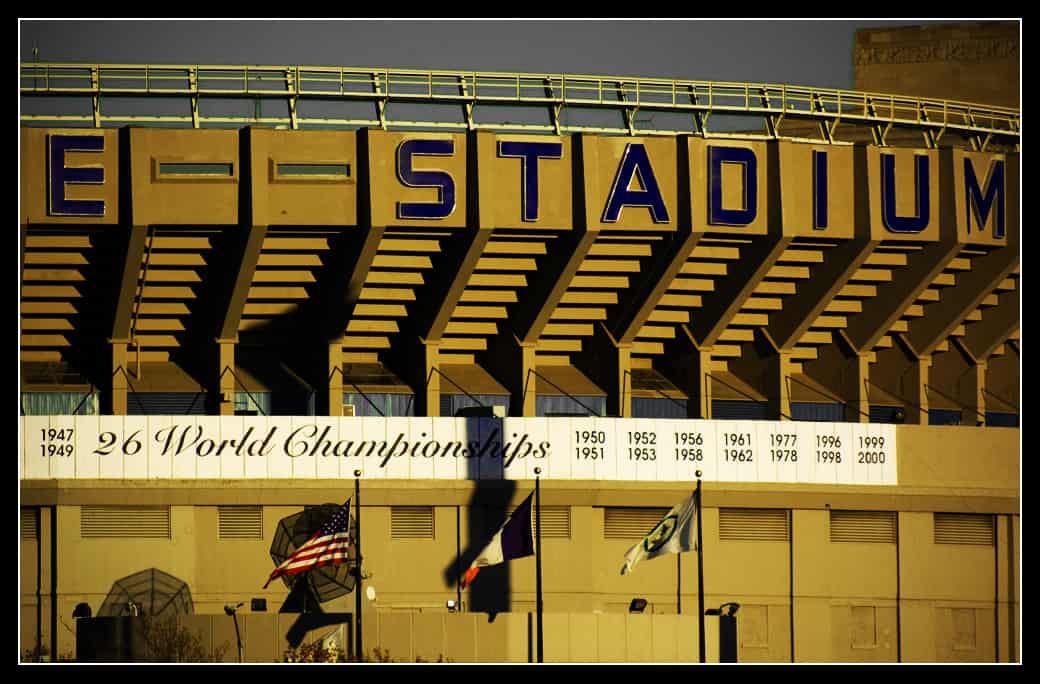

Yankee Stadium at Sunset

I follow baseball like I follow dust. It is there, it happens, sometimes I notice. But when I do notice the game, it is the Yankees I pay attention to. So catching a headline Friday that announced New York was swept by the Tigers in the pennant series did not make me happy.

To understand why a man from Omaha who doesn’t really have a dog in the baseball fight nonetheless pulls for the New York Yankees – and maybe always will – it is important to understand this: when planes hit the World Trade Center eleven years ago, they not only took out the buildings and killed all those people and triggered two wars – they also did something less tragic that nonetheless impacted a huge number of New Yorkers. They knocked out the gigantic television antennas that rested on top of 1 World Trade Center – the North Tower. So that if you lived in the city like I did (acting, catering, French roommate, bad fridge) but did not have a cable hook up, the only station you could watch was WWOR. And WWOR did not show Yankees games.

This meant that when the Yankees eventually made it to the seventh game of the World Series that year against the Arizona Diamondbacks, a lot of people who only had regular TV could not watch at home. The place I was at that night only had regular TV, so we listened to it on the radio. And in listening to such a game, during such a time, something was sealed with the Bombers. Something that probably will not easily go away.

***

Where I was that night of Game 7 was the apartment of a candidate for the New York City Council, Kwong Hui. Kwong was a skinny, 30-ish organizer, who managed to be somewhat humorless and fairly engaging at the same time. He had made some noise in New York labor circles for, among other things, taking part in efforts that exposed the maltreatment of sweatshop workers in Chinatown, (including those who had worked on the Kathy Lee Gifford line of clothing.) Kwong took this momentum and ran for elected office during an opportune year, when term limits were ending the careers of many long-time City Council members. When his workers knocked on the door of my Lower East Side apartment, I volunteered for his campaign.

And then New York’s election day came, and it converged with the appearance of those low-flying planes in the sky, September 11.

The election was quickly cancelled that morning. Kwong and his core volunteers regrouped and turned the campaign into a “relief” effort for people in public housing and Chinatown in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, his would-be constituency.

In the city there was a kind of acid shock. For weeks the air downtown was dusty and sulfurous. Later, a man who had been a medic in Vietnam wrote that the smell was, in part, the odor of dead, rotting bodies.

A lot of people lived with their nerves on just the other side of their skin. In Kwong’s district, they were staggering from their businesses being shut down, their phones not working, the mental and emotional devastation. We knocked on doors, checked on elders, agitated to get air purifiers from FEMA. While this was not the Manhattan financial district community, the heart of the devastation (we were operating just to the east) the people were close enough to need help. Probably everyone in that city did.

While I followed it only marginally – catching TV highlights through restaurant windows, a quick headline in a news stand – during this time the Yankees were making a somewhat improbable run for another World Series title. Games were close, playoff leads reeled back and forth. The shortstop Derek Jeter was doing extraordinary things on defense to keep the Yankees alive. Each time New York won a big game, their manager Joe Torre would bring onto the field everyone’s hero, Mayor Rudy Giuliani. The Yankees fought their way past the Oakland A’s and then the Seattle Mariners and finally into the Series.

In the meantime the election had been rescheduled and our relief work turned back into a campaign. When the Series battled to a seventh game, it took place on Sunday night November 4, two days before the election.

***

So we were all at Kwong’s place, sorting flyers and posters and listening to the game on the radio and it was tied and who knew where this was going. But then, in the top of the 8th inning, the young center fielder Alfonso Soriano hit a solo home run and the Yankees took a one-run lead.

Posada, Rivera, Jeter

The Yankees were suddenly winning late in Game Seven of the World Series two months after the city was attacked by terrorists in planes. Two months after the devastation, the grief beyond what a surviving body seemed capable of bearing, the pain sent forth in waves over the entire region, the woman who jumped in front of a commuter train in New Jersey, the other suicides that followed, those firemen sitting helplessly in front of their open red garages surrounded by flowers and candles and cards from school kids, and the lesser evil of a just war, and wondering how much traction evil loses when it is simply “lesser,” and the Taiwanese organizer from Queens with whom you have fallen into a half-hearted relationship you are not proud of, and we could go on about those days, couldn’t we, pages, books, theories, heroics, lights, shadows, and shadows of shadows…

Nevertheless, coming on to end this madness for at least one night, to heal it for the space of a few champagne-soaked moments was the best pitcher in the known universe.

And this pitcher, the reliever Mariano Rivera, was going to get them out, the other team, because that is what he always did. Rivera was like… similes fail. He simply was. And where he was suddenly there were baseballs in catcher’s mitts, and batters standing like uniformed Cub Scouts lost in the forest, and Yankees piling onto the mound, again.

What is more, Mariano Rivera was just a really nice guy, and laid back and good. A Christian preacher back in Panama, my Lord, but not in your face about it. Everyone loved this guy. The Yankees were going to win. Even though it would feel to some unjust because it would be their fourth title in a row and they were rich and they were the Yankees and etc, none of that really mattered. It didn’t matter because this moment was right, and lifted, and it was all going to work out.

***

There is something about listening to a tight, high-stakes, season-ending baseball game on the radio that can kind of drive you crazy. You feel as if you have way less control over the game than if you were watching it on TV. You also are not entirely sure if what the announcers are saying is what is actually happening on the field. They could be completely making all of this up. You are in dark territory. In a way, it is as if you have to trust the team even more. Give yourself over to these unseen men trying to deliver, in this case, whatever victory a reeling city can lay its hands on. With no images to follow, you are almost closer to them in the dark than you would be in the light.

Add to this the sorrow still hanging over the ashy streets outside, and the odds against an under-funded dark horse candidate trying to change the world one city council seat at a time, and Xiao-Lin’s carmel skin and faint charming lisp that, still, one cannot live by. All of this somehow etches the sounds coming over the airwaves that much more deeply into your heart. The towers go down, and the antennas, and so much else, and a few weeks later you are thrown blind and helpless into the hands of this stacked overpaid unflustered “gutty” endearing ballclub, where you will stay.

And it is the bottom of the ninth, and Rivera walks to the mound.

***

I could be the appropriate journalist. I could for this story check out an on-line file from the New York Daily News or the Arizona Whatever from November 4, 2001 in order to inform the reader exactly how the game I never saw unfolded in its dying moments. I could even put one of those little blue links in this story so instantly you could go to a video, or some Sports Illustrated article about the game.

But watching or reading about that half-inning is not something I prefer to do, and frankly never have. All I’ve got is what I remember. Which is that Rivera fires to the plate, and there is a hit. And he pitches again and there is another hit, this one back to the mound.

And the announcer who may or may not be telling the truth says Rivera makes a throwing error.

Rivera makes an error by throwing the ball into center field, and the runners are safe. And things go on in this way and eventually there is a bloop over the infield and suddenly the “D-Backs” as they are called, have come back and the “D-Backs” have won the World Series and the Yankees have not.

We turned off the radio. We finished folding the brochures. Everyone went home. I left with Xiao-Lin. The Yankees had lost and the towers smoldered and my heart was wayward and two days later Kwong Hui the sweatshop crusader would lose, lose bad.

***

The film of sorrow that overlaid these memories was, for many years after that, unerasable. While New Yorkers soldiered on after 9-11, and our little group had done positive things for lower Manhattan, and it was just a baseball game, still. It all seemed to point to something more insidious out there. Nothing good ever really takes hold. We are all compromised. Violence is a gene no religion can excise. Sin is bigger than everything that is. You can try but you won’t get there, wherever it is you really want to go. We are made like seeds in a crisp pod for these tragic ends.

***

I could end there, and normally I do. In a lot of ways, I do.

Then again, time goes by. Little by little, it just does.

Eventually I left the the city, the girl, the acting. My life changed, quite a lot. Eleven years have passed. The darkness surrounding that night has become less so. And not just because of the years that have gone by, or my own “spiritual growth,” or that New York has rebuilt.

Nor because the wars are drawing to some kind of close. Or that people who lost loved ones are a further day away from the knife points of immediate grief.

All that is true, real and good. But there is something else. Very simply, the Yankees won another World Series. In 2009 New York beat the Phillies in six games, at the brand-new Yankee Stadium, and Mariano Rivera got the final five outs.

Once again, I had barely followed New York’s season. But when it came down to it, I wanted them to win more than I realized. Like some 1950’s schoolboy I found myself cutting out Rivera’s picture and putting it up in my room. I was surprised at how relieved I felt. Just baseball, yes – material, dust. But maybe I had wanted New York’s winning a baseball game to give some kind of redemption. Redemption in a way I couldn’t even quite talk about – for Rivera, the Yankees, the city. Or maybe just for me. For at least a few moments, I think it did.