How long is the gap between knowing that you’re wrong and saying so out loud? Between defensive pride and painful honesty? It may only be ten seconds, but it feels like an eternity.

How long is the gap between knowing that you’re wrong and saying so out loud? Between defensive pride and painful honesty? It may only be ten seconds, but it feels like an eternity.

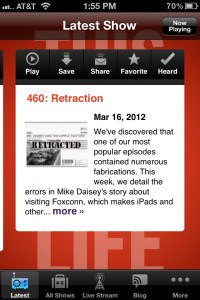

Two weekends ago, NPR’s This American Life ran an episode called “Retraction.” Earlier this year, they had an episode featuring Mike Daisey’s one-man show about the working conditions in the Chinese factories that make Apple products, and later discovered that many of Daisey’s claimed first-person conversations with those workers had been embellished or outright fabricated.

So, Ira Glass and the crew at This American Life ran a full-length retraction episode — which is itself remarkable. They didn’t just print a retraction on their website and walk away. They produced and publicized the retraction episode, in which they explained how they discovered the deception, interviewed Mike Daisey about it, and then reviewed the current facts in evidence about the factory working conditions. Glass more than once takes full responsibility for their failure to kill the original story when it couldn’t be sufficiently verified; they handled it about as well as such a thing could be.

But the retraction is not the most interesting part — in “Act Two” of the episode, interviewing Daisey about the deception, Glass asks him point-blank why he chose to lie when their fact-checkers raised initial concerns. And Daisey pauses. For almost ten full seconds. On air, and repeatedly. You need to listen to it to appreciate the full effect of those ten seconds of dead air; no description can do justice to how painfully uncomfortable that silence is.

But the retraction is not the most interesting part — in “Act Two” of the episode, interviewing Daisey about the deception, Glass asks him point-blank why he chose to lie when their fact-checkers raised initial concerns. And Daisey pauses. For almost ten full seconds. On air, and repeatedly. You need to listen to it to appreciate the full effect of those ten seconds of dead air; no description can do justice to how painfully uncomfortable that silence is.

As I’ve continued to think about, I realized: I’ve been there. Not, thank God, on air or in public — but certainly in confession, I have been the one hesitating, irrationally wishing that if I just wait long enough, some easier or less embarrassing way to say “I sinned; I knew what was right and chose what was wrong” will magically present itself. It never does. In the retraction interview, Daisey never quite manages to admit that he’s lied; he waits those eternal ten seconds and then flinches at the end, which is all the more painful because it is absolutely clear to everyone that he had, in fact, lied. The refusal to admit it doesn’t cover up anything. And I get that too, because when I’m in confession, it’s perfectly clear that I am there because I have sinned, and even then there’s part of me that doesn’t want to say so out loud.

Those ten seconds — whether encountered in the confessional, in a conversation with a friend, or even on This American Life — are an offer of grace, an opportunity for honesty instead of pride. Difficult grace, to be sure — but worth every second.