John Lewis. He crossed many bridges in his life. On Friday, he crossed the final one.

On July 17, 2020, with the death of John Robert Lewis, the U.S. Congress lost its conscience. This legend was the youngest man to speak at the March on Washington next to Dr. King in 1963, and he served seventeen terms in Congress. He was an outstanding model of nonviolent resistance, a Freedom Rider, and an artisan of peace. He called for more than change; he challenged us to love.

Born in 1940, Lewis grew up in the Black Belt town of Troy, a rural town in Alabama, fifty miles from Montgomery. His mother and father were sharecroppers, and he used to spend his Sundays with his grandmother, who was born a slave.

As a boy, Lewis heard many stories about lynchings. He was only four months old when Jesse Thornton was lynched just down the road from his house. Thornton was a popular man, the manager of a local chicken farm, where Lewis would later work himself.

But conversations about segregation and discrimination were frequent among his family members. Lewis would ask his father, his mother, his grandparents, and great-grandparents, “Why?” Their replies were disturbingly consistent, “That’s just the way it is. Don’t get in the way. Don’t get into trouble.” Later in his life, Lewis will offer his response: if you are going to get in trouble, “get in good trouble, necessary trouble.”

Then, in 1955, at fifteen years old, he heard Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on the radio, preaching about peace, nonviolence, and reconciliation.

Redemptive Suffering

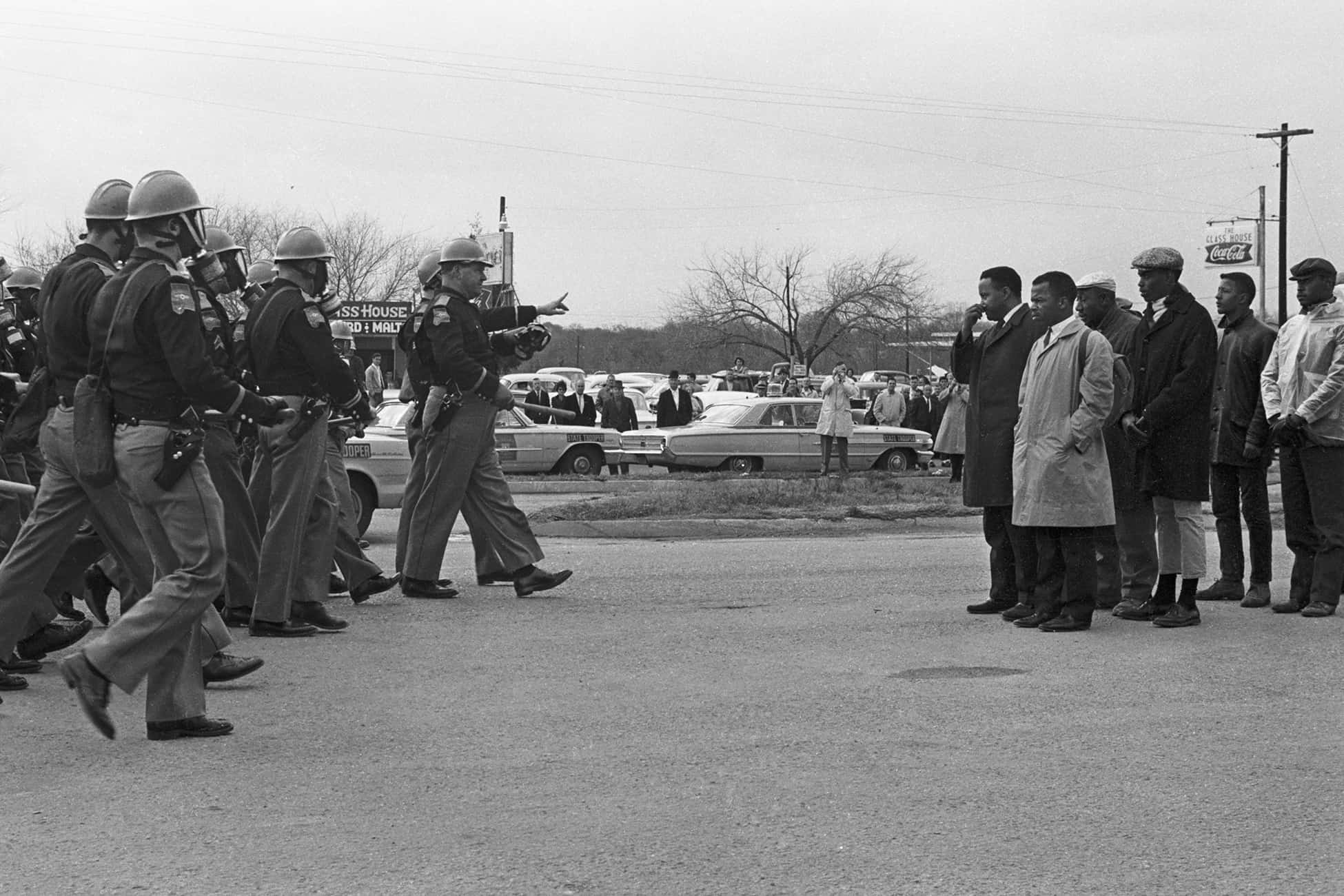

Protestors and police officers face off in Selma, Ala., March 7, 1965, in what’s come to be know by civil rights activists as Bloody Sunday. The iconic photo is part of a documentary “John Lewis: Good Trouble” about the longtime racial equality activist and member of Congress. (CNS photo/courtesy Magnolia Pictures)

By 1960 he had joined King’s movement in the fight for freedom, jobs, justice, equality, equity, and human rights of Black people, including the battle for the Voting Rights Act. He brought with him the discipline of “redemptive suffering,” which he had learned from the Rev. James Lawson. Lawson taught many students the principles of nonviolent resistance, principles which had originated with Mahatma Gandhi.

The discipline Lawson taught Lewis helped him learn that love could never be an empty sentiment. In the face of discrimination and racism, Lewis said that we have to remember that love remains steadfast.

For Lewis, we must be brave, calm, patient to be able to see our aggressors, our oppressors, with a peaceful imagination. Look them in the eye and remember that, some years ago, this person was a child. Someone innocent. Look them in the eye and ask yourself, what must have happened? Had someone taught them how to hate, in the intervening years?

Remember, hate is a heavy burden to bear. Look them in the eyes and don’t ever give up. Never give up on anyone. This is the kind of steadfastness love requires.

In order to practice this steadfastness, Lawson’s group would engage in role play. Lewis used to call it the “social drama.” This role play involved going through scenarios to practice reacting to aggression. What if someone were to call you names? What if someone were to spit at you or kick you? Lewis said you had to go through motions to prepare yourself to respond with love instead of violence. This response required practice.

And the practice, for him, worked. He remained steadfast on Bloody Sunday, during the Selma to Montgomery marches, despite terrifying threats. In his memoir, Walking With the Wind, Lewis wrote that they were walking down the street, and “…then, out of nowhere, from every direction, came people. White people. Men, women and children. Dozens of them. Hundreds of them. Out of alleys, out of side streets, around the corners of office buildings, they emerged from everywhere, from all directions, all at once, as if they’d been let out of a gate. They carried every makeshift weapon imaginable. Baseball bats, wooden boards, bricks, chains, tire irons, pipes, even garden tools—hoes and rakes. One group had women in front, their faces twisted in anger, screaming, ‘Git them n***ers, GIT them n***ers!’…. and now they turned to us, this sea of people, more than three hundred of them, shouting and screaming, men swinging fists and weapons, women swinging heavy purses, little children clawing with their fingernails at the faces of anyone they could reach.” He was beaten until he fell unconscious. He reflected back, “I thought I was going to die.”

But he saw something in these experiences that was liberating, cleansing, redemptive. Something that might open a person to a higher power, a force that is right and moral. The force of righteous truth that is the basis of human conscience. A force that is described as a true quest for freedom, as a true love in action. “Freedom is not a state; it is an act [of love].”

Despite the lynchings of his youth, the recent protests sparked by the death of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and many more, Lewis’s message remains one of hope. Never despair. Have faith and pray.

The death of John Lewis will leave a big hole behind. But his name will be remembered. His commitment to justice through love and nonviolence remains instructive for us all, something to which we might aspire. America lost its soul. The Black Community mourns a wisdom figure. Congress will forever miss him.

John Lewis. He crossed many bridges. Let us build more bridges in his memory.